The following is “The state’s long arm stops Memphis again,” from my 9:01 column published in The Commercial Appeal on October 26, 2016, followed by a June 24, 2015, blog post, “Can We Now Send Nathan Bedford Forest Back to the Cemetery.

First, the 9:01 column:

The State’s Long Arm: Sometimes, it’s easy to forget that Memphis is a home rule government with a charter that is supposed to give it more control over its own decisions. After all, the Tennessee Constitution was amended 63 years ago so cities could adopt home rule and be freed from the interference of state legislators.

That was then. This is now, and City Hall can’t even decide what belongs in a city-owned park.

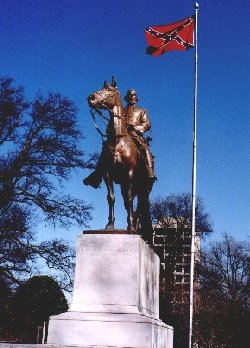

Home rule seems to be four-letter words in the state legislature. Yet again, legislators – including several from suburban Shelby County – prevented the city of Memphis from making its own decision, this time with the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013. The pressure for its passage was simple: to prevent the city of Memphis from moving the statue and grave of slave dealer and Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest from Health Sciences Park. Apparently to make sure no one missed its message, the law was passed in Black History Month.

Last Friday, the Tennessee Historical Commission ruled that the new law now forces Memphis to keep Forrest in a city park no longer named for him. Opining from afar, in a city that was largely anti-secession in the Civil War, Frank Cagle, Knoxville News Sentinel columnist, said:

“I think there is a lot of sentiment in Memphis to erase any memory of Forrest, but the Commission will run up against a buzzsaw in the Legislature, where a bust of Forrest has a prominent niche. My position is that you don’t erase history. You use opportunities to have a teachable moment. Kids in school need to know what happened, the good and the bad.”

Many people agree that we should not rewrite history, but it assumes that it was written right in the first place. It’s said that “history is written by the victors,” but in Memphis and much of the South, it was written by the losers, and this whitewashed history is especially insulting in a city that is 63 percent African American.

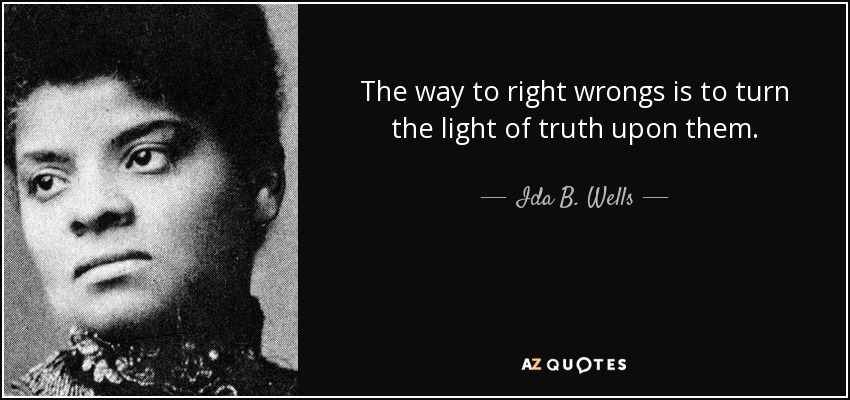

I appreciate Cagle’s point of view about the statue of the Ku Klux Klan’s first grand wizard, but where do I take my granddaughters to see the statues of courageous anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells; Joseph Harris, first African American to own property in Shelby County (after first buying his wife and baby daughter); Ed Shaw, Ku Klux Klan target, City Council member, and wharfmaster; Julia Hooks, the “angel of Beale Street” and leader for social welfare; the African Americans massacred at Fort Pillow by Forrest’s soldiers; or even the legendary Robert Church, prominent entrepreneur sometimes called the South’s first African American millionaire?

It’s the lack of historical context that helped drive the Memphis City Council’s 11-1 vote to remove the general’s grave and statue from the park, a lack of context amplified by Memphis Park (the downtown park formerly known as Confederate Park), which remains the equivalent of Memphis’ Confederate attic with markers and statues, including one for President of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis, added in 1964 as a rebuke to the emerging civil rights movement.

There are people who are emotional about the Confederacy, and they of course have that right, but can’t we all agree that we should spend more time recognizing heroes cut from the most gallant cloth of all: men and women who were not fighting to keep their property, because they were property; men and women not fighting for a beloved heritage because theirs had been obliterated; and men and women who were not people of privilege because all they wanted was the privilege to be free?

The city of Memphis thought it would have more freedom with a home-rule government, but on issues from living wages, employee unions, guns in parks and more, the Tennessee Legislature restricts or reverses Memphis’ ability to govern itself … even when it comes to decisions about a city park.

The following was posted June 24, 2015:

Can We Now Send Nathan Bedford Forrest Back To The Cemetery?

Maybe the Sons of the Confederacy are right. We should not rewrite history. But that requires us to write it right in the first place.

Let’s put the names of real heroes on our parks and monuments, such as nationally prominent Memphian Ida B. Wells, fearless anti-lynching crusader, suffragist, women’s rights advocate, journalist, and speaker. Or Joseph Harris, the first African-American to own property in Shelby County, in 1834 (after first buying his wife and baby daughter). Or Ed Shaw, a target of the Ku Klux Klan in 1868, elected to the City Council in 1873 and served as wharfmaster in 1874, making him the highest paid official at the time.

True Southern Heroes

Sometimes, the emotion attached to defending the Confederacy and trying to whitewash its history make it difficult to realize that it ended 150 years ago. But most frustrating of all is that some people cling to the names of the Confederacy’s beloved but minimize the names of heroes cut from the most gallant cloth of all.

These were not men and women who were fighting to keep their property. They were property.

These were not men and women fighting for their beloved heritage. They were forbidden to even whisper about their real heritage.

These were not men and women of privilege. All they wanted was the privilege to be free.

It’s hard to understand why the defenders of Confederate statues are so hardened that they cannot hear the obvious message that these African-Americans are the true Southern heroes. These are the Memphians with historical meaning, Memphians driven by a simple dream for America to live up to its founding creed.

They deserve to have their names on parks, monuments, and statues, because they are the people who deserve to be remembered, honored and revered by us as a city.

Battles Known For Their Brevity

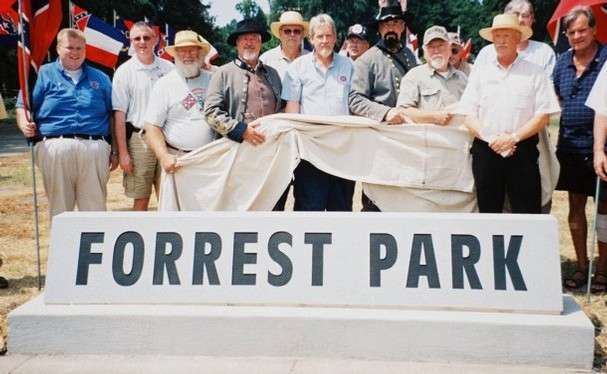

Instead, two years ago, we got a tombstone-like marker erected by a bunch of white guys, replete with Confederate flags and even a Rebel uniform, at Forrest Park. That’s why it was obvious that City of Memphis Chief Administrative Officer George Little made the right decisions when he ordered removed in the face of demonstrations by the local death cult.

It’s tempting to suggest that people honoring American traitors in this day and time need interventions, because for some reason known only to them, these Rebel rousers find it impossible to let go of the past, embrace the present, and prepare for a better future.

Here’s the thing: Memphis’ failure to become a bastion of the Confederacy led to it avoiding the destruction that befell Atlanta, Richmond, and several other Southern cities. Memphis emerged from the Civil War largely unscathed physically and its businesses were reasonably intact.

The Battle of Memphis was one of the briefest and most inept naval battles in American history, but the Confederate navy was demolished. In its wake, Memphis became a magnet for Northern merchants. When General Ulysses S. Grant took command of Memphis for a short period, and, after observing the smuggling carried out here, he said that the disloyalty of Memphians to their own Rebel cause was striking.

The so-called Second Battle of Memphis took place August 21, 1864, at 4 a.m. It was a raid led by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, slave trader and plantation owner, Ku Klux Klan leader, and the antagonist for which the city park was named and where he is buried. His raid was largely a tactical failure and only lasted a few hours, and more than anything, it led to the Union beefing up its forces in Memphis until military rule ended on July 3, 1865.

It’s A Park, Not A Cemetery

At least when it came to Forrest, Memphis Confederate die-hards had a body in 1904 that it could drag from the cemetery and plant in a city park. Finally, a couple of years ago, we stripped Forrest’s name from the park, but that leaves one final thing to do – to return him back to Elmwood Cemetery.

Dr. Aram Goudsouzian, director of the Marcus W. Orr Center for the Humanities at the University of Memphis, summed it up well: “No one is saying we should erase Nathan Bedford Forrest from our history books – our understanding of history. But a public park is not a history book. It’s a public place with a monument that suggests this person stands for values that we celebrate as a community.”

Dr. Goudsouzian, one of 45 faculty and graduate students at University of Memphis who signed a letter supporting the park renaming, made the point that “with rare exceptions,” professional historians find the celebration of General Forrest “distasteful.” In addition, he punctured a hole in the naïve argument that General Forrest’s Ku Klux Klan was a social club and that he was sensitive to the changing roles of black Southerners. Rather, the professor said the Klan was a terrorist group whose purpose was to prevent full citizenship for African-Americans.

In his history of Memphis, Cotton Row to Beale Street, Dr. Robert Sigafoos wrote: “Forrest bore the title of Supreme Grand Wizard. He is believed to have personally directed night riders in terror raids in West Tennessee and Eastern Arkansas…He was particularly hostile to changes wrought by Reconstruction and reacted forcefully.”

Sending Forrest Where He Belongs

There are other people who are in charge of marketing the city who think Confederate controversies have been damaging to the Memphis brand. It’s hard for us to understand how it is anything but that, because a city devoted to being inclusive and one that is dramatically diverse s this one seems to us to be the best message we could be sending out right now, particularly as we try to attract 25-34 year-old college-educated talent, particularly African-American talent, which is now being sucked up by Atlanta, Charlotte, and even Nashville.

Little more than a decade ago, the Memphis Talent Magnet report cautioned against the negative impact of a Memphis brand that relies on photographs of riverboats and other stuck-in-time images that populate websites and that do nothing to attract young, college-educated workers looking for progressive, vibrant cities.

So, for more reasons than just historical accuracy, it was simply time for Confederate parks to go the way of the Confederacy itself, and now it’s also time for Nathan Bedford Forrest to go back to Elmwood Cemetery. If Governor Bill Haslam can advocate for the removal of a bust of Forrest from the state capitol, surely we can remove his corpse from a city park.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

Yesterday’s press conference was so disgusting. Trump is clearly a racist and totally unfit to be President. He must be removed from office. This type of behavior is a disgrace.

Trump is not only a racist but he’s also CRAZY! You can see it in his eyes. The absolute worst president in history.

but he IS president.

Presidents are moral authorities who speak to the highest ideals of this great country. He is in the office, but he is definitely not president.