One of our oft-used aphorisms is “every system is perfectly designed to produce the results that it gets.”

Memphis is just such a system, and that’s why it’s surprising when the news media and others are stunned when a new study or ranking is released that shows Memphis as one of the most “troubled” cities, one of the most “distressed” cities, or with economic indicators going in the wrong direction.

After all, the system is perfectly designed to produce the results that it produces.

All too often, we act as if we are mere victims of forces beyond our control or that things just happened to make us who we are today. It ignores the fact that the present results from choices, and that it was choices we made – not simply forces and factors – that decided whether we stagnated or succeeded.

Seeing Choices as Choices

The simple truth is that choices were made 15, 20, 25, and 30 years ago that resulted in us being exactly where and who we are today. The more difficult fact to face is that we are making choices today – right now – and often we don’t even recognize them as such, and because of it, we settle for incremental progress or decisions that don’t challenge the status quo.

There’s no question that Memphis and the region have always had serious structural issues, some dating back more than a century, and there’s equally no question that they create a high hill to climb. But the persistent idea that we are prisoners of trend lines and data points undermines our most basic ability to recognize choices when they are crystallized right in front of us.

As a result, we still don’t recognize choices as choices, but as merely decisions that have to be made for the short term rather than for the long-term future. Because of that narrow perspective, we regularly fail to connect our decisions as shaping the issues that we discuss with such angst year after year.

Choosing What We Are To Be

One of the most troubling signs is the deepening inequities in the economic system here, but rather than concentrate on creating a system that pays living wages and has more equity built into it, we choose to give more and more incentives to big business. Rather than concentrate on the ramifications of mass incarceration that drives stakes into the heart of thousands of Memphis families, we choose to pursue tougher sentences and harsher punishment that result in one of the nation’s highest incarceration rates while the creation of a just city is within our reach.

Rather than concentrating on how to capitalize on the road network we’ve already paid for, we choose to build more lanes of traffic farther away from the core city when we have the power to take assertive, aggressive actions to reduce the distances between the employee-rich sections and the jobs-rich sections of Memphis. Rather than concentrating on how to increase investments in the public services that bind together the fabric of urban neighborhoods, we choose to put more and more into budgets that are about arrests and convictions. Rather than concentrating on ways to mitigate one of the most regressive state tax systems in the country, we choose to pursue policies that increase the disparity in the percentage of income paid in taxes by low-income and high-income families.

We could go on, but you get the point.

We continue to treat issues as decisions to be made today rather than choices that will define tomorrow.

And to compound things, we rarely see them as interconnected choices or links in a chain of decisions that define the malignant economic segregation, the expanding economic disparities, the dire concentrated poverty, and the hollowing out of the middle class.

Lives Matter

These days, there is a rhetorical tug of war between black lives matter and all lives matter, but more than anything, in Memphis, black lives matter. Here, they are paramount, if we are going to be serious about a successful future for Memphis, as characterized by thicker middle class, higher incomes, more opportunities, better education, and better neighborhoods.

And it only makes good sense that in a city that is 63% African American, and where the African American poverty rate is 30.1% although it’s as high as 60% in some zip codes. In other words, until we have an ambitious plan to capitalize on our vein of African American talent by refusing to see children as problems, by refusing to see people in poverty for their potential, by refusing to accept the status quo, and setting out to be the place that breaks the link between race and poverty, Memphis is sleepwalking into the future.

And that future will be more of the same.

There are plenty of warning signs, such as when the Economic Innovation Group concluded that Memphis is one of the country’s most distressed cities with almost 70 percent of its people living in distress. In one zip code, the percent of people living in distress is 99.1%. The study used seven data points for its rankings, and of course, these kinds of rankings are all about which variables that are chosen.

That said, none of the ones that drag down Memphis’ ranking is a surprise. We’ve written often about them: educational attainment, housing vacancy rates, unemployment rates, poverty levels, median income ratios, percent changes in unemployment, and the percentage change in the number of businesses.

Reeling From The Great Recession

The rankings were striking for the fact that so many of the cities in distress are located in red states (and seem to be competing to see which ones have the worst legislatures). The two data points that seemed to most interest the researchers were housing and creation of new businesses.

It was yet another reminder of how devastating the Great Recession was for Memphis. While it dealt a blow to African American wealth across the U.S., few cities were hit as hard as Memphis, where the economic tsunami wiped out decades of Africa American wealth. As a country where most of our wealth is tied up in our houses, the fact that Memphis was a center for predatory lending only served to increase the size of the waves that capsized so many families. And that’s not mentioning the federal policies for decades that prevented African Americans from increasing wealth through home ownership.

And yet, many talk about the Great Recession and the attendant deepening problems of inequality as if it was as a natural disaster, rather than as something that occurred because of choices being made about policies and plans. In Joseph Stiglitz’s book, The Great Divide, one of the chapters is titled “Inequality Is a Choice,” and his point is that as a nation, we make tax shelters the higher priority rather than higher minimum wages and we put greater emphasis on subsidies for corporations rather than services to help children break free of the cycle of poverty.

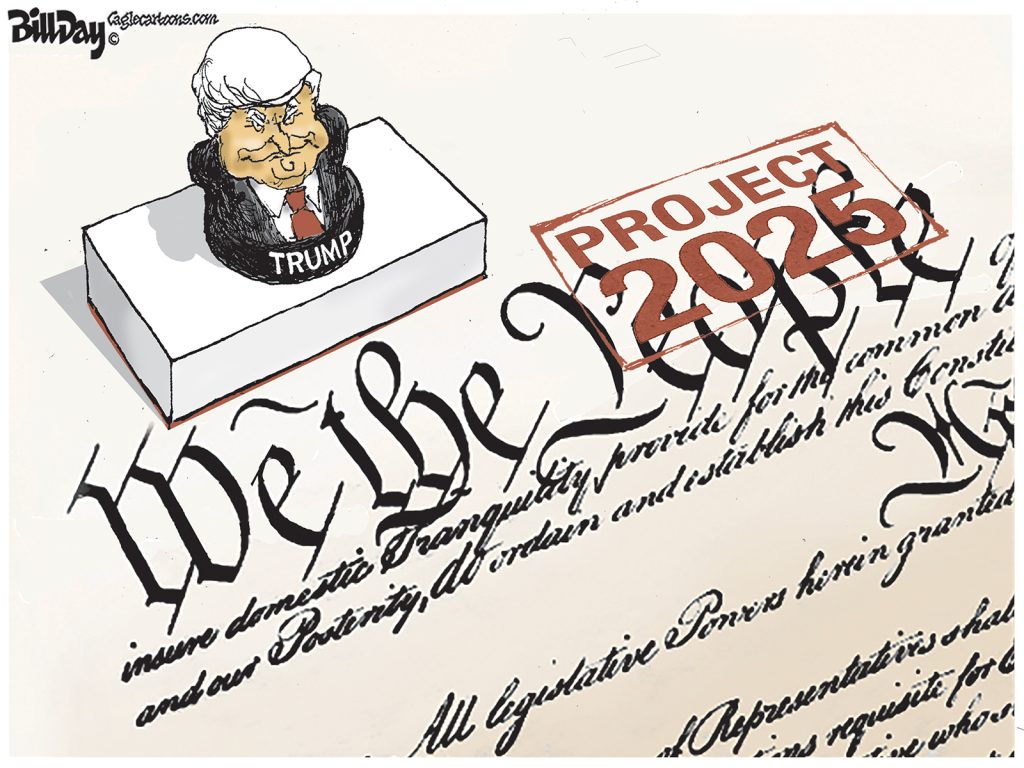

Meanwhile, poor people are regularly portrayed as “takers” and people looking for free rides rather than being buffeted by choices that are more favorable to Wall Street and the 1%. And, here at home, the Tennessee Legislature forbade – and forced Memphis to reverse – an ordinance for a living wage, it refuses Medicaid expansion to improve the health of hundreds of thousands of people, it pushes more and more guns into the public sphere, and institutionalizes an unfair tax system by adding a Constitutional prohibition against a state income tax.

Inequality Isn’t The Problem

Here’s the thing: in Memphis and Shelby County, we have some tools that can improve the toughest issues like inequality, but the underlying problem isn’t the inequality itself. It’s the fact that we don’t recognize that there are choices that we can make to change things – or that we don’t even see them as choices in the first place. It is in seeing decisions differently – as choices – that we change our perspective, consider alternative scenarios, and look to the future with greater confidence. It is in seeing that we are making choices that we move past superficial ideas – like the idea that the answer to poverty is simply to create jobs, any jobs, and that any road is a good road – and see issues in new ways and in a new light.

Sadly, there is less economic mobility in the U.S. than in class-conscious Europe. Here, 70% of Americans raised at the bottom never reach the middle, African American children are 11 times more likely than white children to grow up in a high poverty neighborhood, and children born in poverty are highly likely to stay there.

Put simply, Memphis cannot succeed as long as 20% of its population is living on $13,520. It results in less money in local businesses’ cash registers, less money to be spent on enrichment activities for children, less money for better lives. Memphis has become a city of extremes – one where the poor are very poor and the rich are very rich.

The end result is a city with two few revenues for the services that are vital for the lives of its people, particularly those in neighborhood characterized by concentrated poverty and blight and low densities. Among the 50 largest cities, Memphis is #16 in income inequality, which should be encouragement that we should start now, right now, to start making choices that can make a difference.

Setting The Right Priorities

We are at a point when economic inequality has worsened (just as it has nationally), when economic policies are making it worse, and when ultimately the inequality will be destabilizing to the region because it is a drag and deterrent to economic growth. Just as third world problems stem from those at the bottom feeling disenchanted, disenfranchised, and marginalized, Memphis shows signs of similar growing pressures.

The answer seems clear: to succeed and to achieve its vision, Memphis must set opportunity, wealth creation, and financial resiliency for every Memphian as top priorities. It is the strongest medicine for a better city and the best road to a better future. It begins by making better choices.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

Memphis has made poor choices for decades. In spite of continuous failures, the mistakes and poor leadership continue. Quite simply Memphis is not succeeding and the misery index just keeps rising. The decline of any city is painful, especially if you live here.

Reading this is distressing. So many bad choices. Hopefully the elected officials will read this too.

Just like this article states, Memphis shows many of the same signs as places in the third world.

This city is its own worst enemy

Don’t know if you knew it or not, but Memphis tops the nation in millennials moving here, coming in at #3, according to the most recent poll in Time. I moved back here from Nashville, yes, Nashville six months ago and couldn’t be happier.

I know that Memphis has been limping in years past but it is definitely getting its “cool” going with downtown revitalization, along with many other developments and improvements such as Shelby Farms. Nashville, trust me, is not what it is cracked up to be. Crime is rising and local news is all about affordable housing. I suppose the housing shortage is a good problem to have, but it is still a problem.

Memphis, no doubt has an uphill climb ahead.

Let’s focus on what’s going right instead of what is going wrong all the time.

38103: The Time magazine seems to conflate an increase in 25-34 year-olds with in-migration of millennials, and as a result, it overstates the conclusion. The Memphis increase is more likely to be related to an aging into this demographic group by younger Memphians.

As we have written often in the past eight years, Memphis is unique in the higher percentage of its population that is under 18 and about eight years ago, we said this is why when it came to the future workforce (millennials) that our first priority should be to get the students in the classrooms into lines getting college diplomas and then secondly, to try to recruit young workers from outside Memphis. In-migration of millennials is slow and so the higher impact option for us was always to concentrate on the bulge of young Memphians moving into the 25-34 year old group.

There are many questions about Time magazine’s article and we’re trying to find the time to do some research to answer them. What part of the total are Memphians aging into the demographic group, the educational attainment of the group, etc.?

Memphis

We are not trying to burst the bubble of the Time article but we believe that we have to understand them to keep our eye on our highest priority.

38103. There is simply no comparison of Memphis and Nashville. As this blog has pointed out many times before, no city in America right now is booming the way Nashville is growing especially in high paying jobs creation. It’s a tale of two very different cities and Nashville has far surpassed Memphis which seems to be just barely treading water.

Understood.

Will look forward to your future post on it.

Thanks, 38103, for your comment.

To read the many positive things going on in Memphis, here’s my column in Thrillist last year: http://www.smartcitymemphis.com/2016/07/thrillist-memphis-deserves-a-place-as-a-great-american-city/

I am pretty sure I read that, and again thank you.

While there are obvious things that need to be done now to make Memphis better, bring in businesses and corporations, create jobs, fix our education, taxes, etc., one thing I believe is killing the image of Memphis: perception.

Perception, while abstract, has a way of going to the bank and drawing interest, whether it be positive or negative. I think that’s one of the biggest challenges Memphis is facing, simple yet profound.

And the part that kills me is that a lot of the time it is undeserving.

Unfortunately, perception is reality to most people. The overwhelmingly negative perceptions of Memphis hurt.

With the great things currently going for Memphis a negative can easily turn into a positive.

That, coupled with applied pressure on our elected officials to do their job, and they’d better do their job right now.

We hope that in our constant press for Memphis and Shelby County to develop a greater sense of urgency to deal with serious structural issues and our posts hoping to spark that, we do not overlook the good things under way.

There are plans for branding that will address perceptions, but we believe that the most impressive image that we could project to the nation – and to young workers – is of a community united behind a bold vision to change our trajectory on key economic indicators, to increase opportunities for all Memphians, to attack economic segregation, and to mobilize a people united behind their insistence for a bright, bold future.

Well put, smart city. I’ll close my end of this thread, but will look forward to future posts on the topic of perception we’ve discussed here.

Thanks for the conversation and for caring about these issues and solutions.

Didn’t the city recently launch a new effort to help the Memphis “brand” by hiring a staffer who had previously worked for the National Park Service? I’m not sure if this is a city government function or a part of the convention and visitors bureau. Hopefully it’s not duplicating efforts because the CVB led by Kevin Kane have a miserable track record. A lot of work is needed in this area for sure

“Rather than concentrating on how to capitalize on the road network we’ve already paid for, we choose to build more lanes of traffic farther away from the core city when we have the power to take assertive, aggressive actions to reduce the distances between the employee-rich sections and the jobs-rich sections of Memphis.”

Doesn’t a lot of this go back to Federal “choices,” e.g. when Trent Lott was Senate Majority Leader he made sure that I-69 went through Mississippi, creating a major outer beltway? Likewise, is it Memphis’s fault that the financialization of the economy benefits an insurance capital like Nashville but hurts almost everywhere else?

What’s weird about this piece is that in emphasizing radical voluntarism, i.e. the position that the will is the primary force in (the universe and) human affairs, it echoes George W. Bush’s view of politics as a series of “decision points” and the Presidency as “The Decider.” This is the neoliberal/meritocratic view of everyone and everything as an entrepreneur solely responsible for his or her own economic destiny. It’s empowering but alienating in minimizing the importance of solidarity and collective responses among communities, cities, and countries to common problems. Pragmatically, that is a problem because historically cooperation has been a prerequisite to historically successful policies/approaches/decisions.

For example, Memphis has been hurt badly by the anticompetitive Northwest-Delta merger, which destroyed thousands of airport jobs and cut our daily flights by more than 75%. That merger has lead to inequality as workers were laid off and Delta quasi-monopolitistically reaped fatter profit margins. You could call all of this a “choice.” But it wasn’t a choice made in Memphis. So don’t imply that our community is entirely to blame for all our struggles. The NW-Delta merger was the product of a whole series of choices at the DOJ Anti-Trust Division, the FAA, NW, Delta, and all their attendant investment bankers and merger lawyers. All of whom were influenced by vast changes in power relations between industry and government, idealogical changes like the rise of University of Chicago style economics, and political changes like the creation of Third Way Clintonism. And all of these changes were shaped by the end of the Cold War, globalization, the end of the gold standard, technological innovation, etc., etc.

In other words, “choices” are embedded in thick networks of politics, culture, economics, institutions, technology, etc. A key question is how do these huge structural forces shape the choices presented to us at the ballot box and in the market. For instance if the GOP poisons Obamacare without killing it, Memphians may have more but worse insurance plan options/choices than before.

To ignore structural forces is to ignore unintended consequences and competing interests in a way that gives human affairs too much intentionality. Yes, it’s trivially true that “the system is perfectly designed to produce the result it produces” if by “system” we include all forces. But not all forces are designed or even human. When Las Vegas introduced an expensive trash collection fee and citizens responded by trash dumping, the system of politics and citizen psychology deterministically produced a certain result, but the city council didn’t intend a dirtier city. When the Forestry Department’s policy of fire prevention backfired, so to speak, into fewer but more massive forrest fires, the human and ecological systems were at odds. In both cases, bad choices were made, but they were bad they ignored bigger, structural factors.

So my question is: what choices should Memphis have made 15, 20, 30 years ago and who should have made them?

We have written for years about structural realities in Memphis so this post was made within this context. We wrote a multi-part series a few years ago that listed the choices made decades ago that were crucial in setting the present trajectory. For example, when the county commission fueled sprawl, it was never considered As a a choice – between developers’ interest and deterioration of the core city. Perhaps we will post our list of choices again, because unfortunately, they remain relevant. They are generally decisions made by the influential class, often to the detriment of other sectors of the population. The lack of serious public involvement in these pivotal points does not produce multi-dimensional impact and remains a serious downside to choices made with broad-based support.

Eric Beeman: yes, David French was hired and his strong background in branding bodes well. Branding is different than the marketing by CVB and Chamber but will undoubtedly be coordinated with it.

Anonymous: we have written often about the shameful political games that begat I-69, however, we were thinking more of the Nine figure funding this community received in lieu of interstate through Overton Park which was spent to incentivize sprawl. Also, county government’s decision to build massively wide major roads made little economic or budgetary sense.

Ok, thanks for the response. I’m sorry my post missed the broader context of your other posts. It would be super helpful and useful to see a repost of your list of choices. Honestly, I feel like you guys know all kinds of interesting and useful things about urban policy and Memphis history, but I don’t have the time to go back over dozens of old posts. I, for one, would certainly appreciate a few posts filed under “start here” that lay out your philosophy and if you included some suggestions for citizen involvement, I’d probably take you up on some of them. I mean, I write my congressman about once a month and I vote in every election, but I have no idea where to start when it comes to pushing for better planning or local governance. I read a good book on New Urbanism several years ago and found it compelling but never have figured out how to push for some of its benefits. I bet there are plenty of people like me out there.

As I think about past local decisions, three different levels of hindsight occur to me:

1) Stuff that everyone should do that we didn’t. We should have spent more on schools. We should have tried to create a local culture that values education and the arts more widely. We should have spent more on drug rehabilitation, etc. Better at the basics.

2) More advanced urban planning stuff. It’s pretty cool that we got so much Federal Hope VI money to revitalize housing projects, but we probably should have forged out that integrating residents into new neighborhoods would be tough and provided more help with that and ways to keep communities intact. We could have adopted some smart zoning rules and some plans that drew residents into attractive, central, safe neighborhoods with some density–anything to keep Northern Mississippi from leaching residents into sprawl.

3) Strategic stuff that better anticipated changes in the economy. Foresight is the hardest, but what if Memphis leaders had traveled around the world in 1970 à la Japanese delegations of the 1800’s or hired genius consultants or some other way figured out that deindustrialization was going to be a big deal for heartland American cities? What if we had anticipated that cities in the bottom quartile of education were heading for deep trouble? What if we had launched a long-term project to develop a growth industry like biomedical engineering or computer security?