There is a lottery in Shelby County every day for an average of 37 people.

The winners get a head start to more education, higher income, better health, and less lifetime stress.

The others get the odds stacked against them and face obstacles that will come to define their lives.

It’s the ultimate Powerball.

The Wrong Birthright

It’s the lottery ticket that affects the more than 13,000 babies born in Shelby County this year. About 4,000 of them draw a losing number, born into an extreme poverty that has more in common with the Jim Crow South than modern Memphis.

For these 4,000 babies, the hill that rises before them is steep and marked with formidable obstacles, and as they travel it, the pervasive message they receive is that their community doesn’t value them and believes their futures are not worth fighting for.

In other words, the birthrights for too many Memphis and Shelby County children are being set up for failure. That’s why the interventions piloted and provided here are not only vital for these children, but for the city and county themselves. Research suggests that a single intervention is not enough to improve the odds for these children, and instead, success results from multiple interventions over many years.

The good news is that there are interventions with proven records of success. We think of Girls Inc., Boys & Girls Club of Greater Memphis, Pre-K programs, Knowledge Quest, YMCA, Memphis Athletic Ministries, Early Success Coalition, A Step Ahead, Le Bonheur Early Intervention and Development, and there are more, and the effectiveness in this area is strengthened by the research, data-driven solutions, and partnerships of Seeding Success.

The challenge is to increase their capacity and bring them to scale.

Signs

We are not completely sure how many children require these life-altering interventions, but we suspect 65,000 is a reasonable working number; however, the number of individual children receiving interventions cannot be determined with any accuracy, but we do know that our emphasis should be on funding what works to expand the programs so the maximum number of young people are touched.

Often, the organizations providing the interventions are met with a collective shrug. It’s akin to public meetings when someone suggests that an organization should set fighting poverty as its mission and everyone’s eyes glaze over.

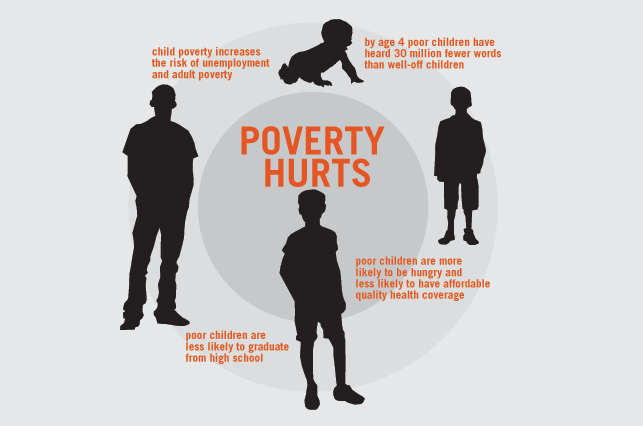

There’s no argument that It is national disgrace that one in five children living in poverty, but there is no greater blemish on Memphis’ reputation than the fact that our poverty rate for children is twice that high.

If Memphis celebrates its 200th anniversary in two years without a comprehensive, imaginative, and bold plan to attack poverty that has been a drag on this community for more than a century, the city should not just be embarrassed. It should be seen as a sign that the city has given up on itself and its ability to control its own destiny.

Hyper-local Politics

We’re not saying that people in poverty are mere victims of circumstances. It is nothing short of inspirational how many children born and reared in poverty manage to escape its snares. And yet, the political philosophy controlling the federal government is creating policies on the tired, old adage that people in poverty “should pull themselves up by their bootstraps” or that poor people are simply guilty of making bad choices.

Meanwhile, there are liberals who cling to notions about the “nobility of the poor” while the people they are describing are more interested in opportunity than nobility.

We now appear to be headed into a political cycle when strings of the safety net will be snipped as conservative politics is characterized more and more by its meanness and its lack of guilt in refusing to rescue children from conditions that politicians could only imagine.

If all politics is local, the risks for Memphis’ children in 78 census tracts are hyper-local, a brutal web of concentrated poverty, crime and violence, discrimination, and opportunity youth. The conditions are sometimes compounded by poor schools, police profiling, outdated community facilities, and an underground economy.

Declining Odds

Remarkably, when these young at-risk children encounter barriers in school or in a program teaching them skills and drop out, no one tracks them down to understand the problem and work to solve it so the youth gets back on track. They are simply lost. Their names are removed from school rolls and program rolls and life goes on.

It speaks to one of the problems that result from conventional opinion. If these youths fail, it’s often seen as their fault rather than the systems that allow them to vanish without a word.

The research is clear: it matters if a child is sometimes poor or persistently poor (those who live more than half their lives from birth to 17 in poverty).

According to the Urban Institute, the persistently poor are 43% less likely to complete college than sometimes poor children and 13% less likely to complete high school; parents’ educational levels are closely related to the academic achievement of persistently poor children; residential transience is related to lower academic achievement for persistently poor children (those who move three or more times before they are 18 are 36% less likely than sometimes poor children to enroll in college and 68% less likely to complete a college degree by the time they are 25; and multigenerational households improve the odds for persistently poor children to complete high school and enroll and complete college).

The family structure of children who have been poor is unrelated to their achievement, including living in a female-headed household; however, for persistently poor children, the longer they live in a female-headed household, the less like they are to complete high school. Two other factors are precursors to lower adult achievement: girls’ teenage pregnancies and collisions with the criminal justice system.

Increasing Lottery Winners

The researchers for the Urban Institute found that 16% of persistently poor children become successful young adults, meaning that between the ages of 25-30, they are consistently working or in school and are not poor. There is other research that indicates that the percentage for poor children in Memphis is much lower.

But using the 16%, it means that 84% of persistently poor children are not succeeding if we do nothing, depriving Memphis of workers, an expanded economy, more stable families, lower health costs, lower criminal justice budgets.

What this means to us is that every program in and every expenditure by local government should be required to answer the questions: how does this program improve the odds of children and youth trapped in poverty, and if it doesn’t, how can it be retooled to do so?

At the same time, we should mobilize all of our political and civic influence to lobby state government for smarter, more humane policies for the neediest among us, and finally, we should shout until our voices are heard in the nation’s capital about the ways the proposed budget, health care plan, cuts to food assistance programs, and other policies will decimate our ability to address the cancerous poverty in our midst.

The pay off for each child who enters and completes college is more than $1 million in income. As the late Senator Everett Dirksen said: “A million here, a million there, pretty soon, you’re talking real money.” It’s real enough for Memphis and Shelby County to take a stand to increase the number of our lottery winners because the community’s success, just as theirs, depends on it.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

This is very sad to read.

Indeed there is no greater blemish on the reputation of Memphis than our high poverty rate, especially child poverty.

Poverty is everywhere in Memphis.

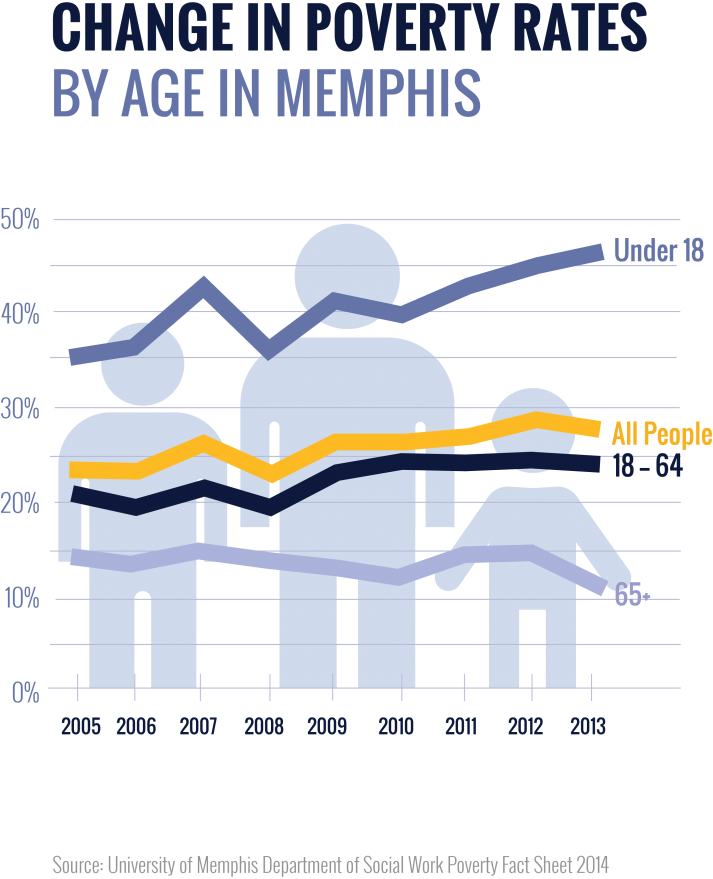

I sorry to be such a contrarian to such a good article. But poverty is not a local problem. We have a lot of local poverty largely based on many years of poor education and racial injustice. But the solution to poverty is not to be found locally or even in Nashville. Look at the graph above. There are two groups that do not work — the young and the old. The young are very poor and the old are not. Now, what is the difference between the two — the old have more money. For the old we have Social Security, Medicare and a variety of retirement income gimmicks that transfer income form the currently working to old people. We do not have the equivalent for transfer programs for the young. The solution is national in scope and simple. If you don’t want the young to be poor, you have to transfer money to them. There is the old exchange between Fitzgerald and Hemingway. Fitzgerald, “The rich are different.” Hemingway, “Yes, they have more money.”