Back in 1976 when Shelby County Government was restructured, it got more than a mayor.

It also got a culture of competition and rivalry between the newly modernized county government and its City of Memphis counterpart across Main Street.

Memphis had voted in 1963 to end its commission form of government on the basis of installing more professional management. In the intervening 13 years before Shelby County Government did the same, it maintained its commission form of government with a commissioner in charge of finance and administration, another in charge of health services, and one in charge of corrections and public works. Meanwhile, the Quarterly County was the county’s legislative body, but it also was a center of considerable power which resulted in blurry and confusing lines between the administrative and legislative functions.

As a result, in 1974, Shelby County voters to restructure to establish clear accountability and the change took place in 1976. As a result of the county vote, there were two mayors in the largest governments in our community.

Fussing and Feuding

With two mayors, it was predictable that there would be some tension and tugs-of-war, but they were magnified often by the fact that the county mayor – in order to command attention and credibility – often had to elbow his way onto the stage for ribbon-cuttings and major announcements.

It did not mean that the mayors could not work together on important projects or programs, such as recruiting International Paper’s headquarters from Manhattan and saving St. Jude Children’s Hospital from moving to St. Louis, but it did require their respective staffs – who worked well and liked each other – to regularly mediate tensions, work out questions like who gets to cut the ribbon or make the announcement, and set protocols about speaking order on programs.

In other words, along with a new mayor came new feuding, which continued in various degrees until the present occupants of the city and county mayors’ offices.

But that was only one reason for the stresses between City of Memphis and Shelby County Governments. There was another one, and it was carried over from the old Shelby County Government.

It was county government’s more than a century old fixation on the area outside Memphis to the detriment of the area inside the city.

Law of Unintended Consequences

At one point, the Quarterly Court had 50 men as members. The vast majority of them lived outside Memphis despite the fact that the vast majority of the county’s population lived in the city. It was a time when every small town had its own commissioner, and services were grudgingly provided to Memphis while services in the towns were being regularly subsidized, if not wholly provided, by county government (which meant they were being largely paid by Memphis taxpayers).

That imbalance would end with the landmark ruling in 1962 of the U.S. Supreme Court in Baker v. Carr, the lawsuit filed by Charles Baker, chairman of the Shelby County Quarterly Court. It was the legal example of “being careful what you wish for.”

Mr. Baker alleged that State of Tennessee Constitution required the redistricting of the Tennessee Legislature but that had not taken place since 1901, and because of it, Shelby County was underrepresented in the State Capitol. The Supreme Court ruled in Mr. Baker’s favor, but here’s the irony: the court’s “one man, one vote” opinion also meant that Shelby County’s legislative body had to be redistricted in proportion to reflect the county population.

That did not mean that county government did not continue to give the area outside Memphis disproportionate attention, and it was in that context that a comment still sometimes heard today was created. When told about a problem by a citizen, a county official would ask: “Is that in Memphis or the county?”

Of course Memphis was in the county (in fact, it is the county seat), but the comment is a revealing insight into the way that county officials viewed the world. People who lived “in the county” lived outside Memphis.

Throwbacks to the Old Days

We say all this as back story to recent comments suggesting Shelby County withdraw from the Memphis and Shelby County Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA). Commissioner Steve Basar said the CRA benefits Memphis more than the county, and Commissioner Heidi Shafer said that county government should exit because the work of the agency benefits the city more than the county.

The comments were direct throwbacks to the days when county government failed to understand that supporting the success of Memphis was in fact supporting the success of Shelby County. That has never been more true than it is today.

If there is a problem, it does not result from county government remaining a partner in the CRA. Rather, the problem is the “we versus they” framework perpetuated by the commissioners.

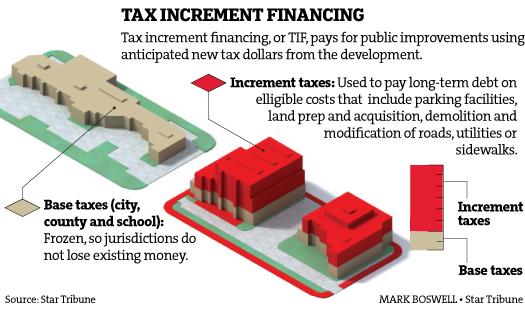

The CRA creates Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts which issue bonds to pay for new infrastructure and then capture property tax increases to pay them. The TIF districts in Memphis are in Uptown, Highland Row, and Graceland. In addition, there is a TIF in Millington benefiting The Shops at Millington Farms.

As we have said before, we prefer TIFs to PILOTs because TIFs are self-financing and front-end-loaded. Recipients of TIFs produce tax revenues that are then used to pay for public improvements, whereas with PILOTs, the cost of services required by companies is shifted to homeowners and smaller businesses. Perhaps, that’s why the other major cities and counties in Tennessee have used TIFs much more widely than Memphis and Shelby County and use PILOTs sparingly.

Modern Fiction

The question about Shelby County Government’s participation in the CRA surfaced when the board of commissioners heard a proposal for a TIF to fund better housing and neighborhood improvements east of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Rather than debating the merits of the project, Commissioners Basar and Shafer tapped into the “this helps Memphis but not Shelby County” fiction, suggesting that county government should keep the $4 million in yearly property taxes that would support the revitalization of the distressed neighborhood.

It is strange that similar comments were not heard when the Graceland TIF and the Millington TIF were being approved. In fact, when the latter TIF was established, Terry Roland was then Shelby County Board of Commissioners Chairman and he said: “I am so proud that my hometown utilized a TIF with this project because it has become a catalyst for future development in Shelby County…The collaboration is an example of what we can accomplish when everyone works together.”

Commissioner Roland was right. It is impressive what we can get done when everyone works together.

Going for Consistency

As for saving county property tax dollars, the Shelby County Board of Commissioners in 2013 cut the maximum term of a TIF to half of the maximum allowed by state law: 15 years instead of 30 years. The $4 million at the root of the commissioners’ concerns amount to 0.003% of the total county revenues annually.

More to the point, we are unaware of any similar concerns raised by these commissioners in the past 15 months as about $60.2 million in Shelby County property taxes were being waived for companies moving out of Memphis to county towns (and of course, Memphis taxpayers paid most of this entitlement).

In other words, if the commissioners are concerned about the “city” benefiting more from the CRA and are willing to pull the plug on the county’s partnership agreement with the CRA, they should apply the same standard to all cities. They should call for the end of PILOTs that use “county money” to help the towns.

After all, Memphis is just as much in the county as Germantown and Collierville.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

And yet Basar wife’s business is shepherding development projects through Memphis city government.

So true. It’s pure conflict of interest. If you want to know what Basar is fighting for, just pull the cases she’s handling in City Hall. If you want to know what he’s against – Pinch District, CRA – it’s on projects she’s not getting her way.

Always the same. Follow the money.