One of our favorite park advocates is Peter Harnik, who retired last year as director of the Trust for Public Land’s Center for City Park Excellence. We can think of no one who is more responsible for the revival of the urban parks movement and is more eloquent and persuasive in his pass for parks. But equally important, he backed up his passion with data that ranked cities on their support for parks – Memphis is #85 out of 100 largest cities – that challenged cities to do more to improve their livability and quality of life.

In a recent blog post, we quoted part of his going away speech October 7, 2016, to the National Recreation and Park Association Conference. Because of its pertinence to Memphis, particularly Overton Park, and his mention of the Memphis park challenge, we’re publishing a much abridged version of his speech:

When the Center for City Park Excellence was created in the year 2000, the nationwide city park movement was in a paradoxical quandary. There were many thousands of city parks, but there was no movement. The city parks movement had parks but no movement. What had once been a full-fledged groundswell back in the 1870s and 1880s – and even well into the 20th century – had pretty much run its course, and all that was left was the residue: the actual parks, many of them in disrepair.

Between you and me, I think the explanation went deeper than these broad generalities (lack of vision and lack of enthusiasm about cities). I think it related to the issue of “Who owns the parks?” Without ownership, you can’t have a movement. I don’t mean physical ownership – legally they were ours. I mean psychological ownership.

Idealists and Realists

I’ll tell you how this came to me. I was working for the Trust for Public Land, whose mantra back then was “We buy land for parks.” Every acre was good and two acres were twice as good. But frequently, when we tried to sell our beautiful parcels to city park departments – even when we offered to give them away – they said, “No, thanks.” Many didn’t want more parkland. This was stunning – unimaginable. How could a park department not want another park? Well, for just about everyone in this room, the answer is obvious. You don’t want more land because you can’t take care of what you already have. Advocates are idealists; managers are realists.

You can’t properly manage what you’ve got because you don’t have enough money, enough staff, and enough political clout to ward off people’s crazy ideas about what to do with “vacant land.” You don’t have these things because you don’t have a cadre of supporters lobbying for you (and of course you’re not allowed to lobby on your own behalf). So, your realism leads you to pessimism. It led Janet Miller of the Wichita Parks and Recreation Commission, to say to me, “Our park department has had so many cuts it’s been forced back to a 21-day mowing cycle, 28 days in some places. If I cut on that schedule in my own yard, I’d be given a ticket.”

That’s the pessimism. Meanwhile, the idealism of the advocates is thwarted, leading them into a spiraling sense of outrage. But neither pessimism nor outrage is a good way to build political strength or attract money.

Money. What we have learned about money in the past 16 years? Well, one thing we learned is that everyone wants to spend it, but no one wants to make it available.

Most people think money comes first, but I believe landscape architect Mark Johnson got it right when he said, “Money flows upward to vision.” Vision means defining the problem and figuring out a solution. Money comes third. Most people get it backwards.

It’s About Political Power

Let’s face it: urban parks are not cheap. It can easily cost three quarters of a million dollars for a playground. Two million dollars per mile for a rail-trail. Three million for a neighborhood park. Thirty million for a downtown park. But nothing urban is cheap, and the budget is what elevates the plan from platitude to reality. Courageous park directors and mayors recognize that the vision is what often serves to motivate, unify, and strength pro-park activists.

One other thing about money: dollars attract more dollars. Those who think small and husband all their resources until the pot is completely filled often never get there. That’s why partnerships with both public and private entities – and what we call a “funding quilt” of many different sources – are so important in building a war chest and combatting the powerlessness that often befalls the parks movement.

Basically, I realized that, we don’t know anything about city parks. There are tons of opinions, and there are tons of prescriptions of what should be, but no data. By the way, at the time, practically everyone assumed that Central Park was the largest city park in the country. Actually, it never was, and from out latest report, it is now #167 and falling.

Our main problem is lack of political power – the lack of a people-based movement. In our world, political power means Friends of Parks organizations. Not paper structures appointed by politicians to advise agencies, but rather real, freestanding organizations with a force of their own.

I mean an entity that is separate and makes its own decisions.

The Perfect Structure

In my opinion, the ideal structure in a city looks like this: 1) a citywide park and recreation department, 2) a citywide park foundation to do private fundraising, 3) a little volunteer friends organization for each park to keep an eye on things and help out, and 4) a citywide Parks Friends organization, an umbrella of all the small friends groups, to organize citywide political events and to oversee citywide lobbying for parks. To my knowledge, there are five cities which currently have or come very close to having this structure: New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Chicago, and San Francisco.

I’m a fan of parks for numerous reasons but probably the prime one is for their role in smart growth – their role in fostering compact, walkable neighborhoods that also preserve the rural, outlying forest, fields, and farms. I hope that one day, the phrase, “Park-oriented Development” will be as prevalent at “Highway-oriented Development” was in the 60s and as “Transit-Oriented Development” is today. People like to live near parks, they’re even willing to pay more for a house or an apartment with a park view or easy access – and parks are good for people, thanks to cleaner air and a place to exercise and unwind.

Our calculations show that about 100 million urban and suburban residents are more than half a mile from a park – that’s about one-third of all Americans. If the nation committed itself to assuring that all these folks can walk to a park in 10 minutes, what would that take? Doing it purely by creating new parks – by dropping new parks into the neediest neighborhoods – would require the creation of nearly 60,000 new parks in America’s cities, suburbs, and towns. This is a major undertaking: in the nation’s history so far less than 24,000 bit city parks have been created. Fortunately, there is a second way to get everyone within a 10-minute walk of a park: bring more dwellings to the existing parks – increase the density around them.

Cars Aren’t For Parks

The first use of the word, park, meaning “an enclosed tract of land held by royal grant or prescription for keeping beasts of the chase” occurred in the year 1260. What’s worse is that car park was really invented as a park for cars.

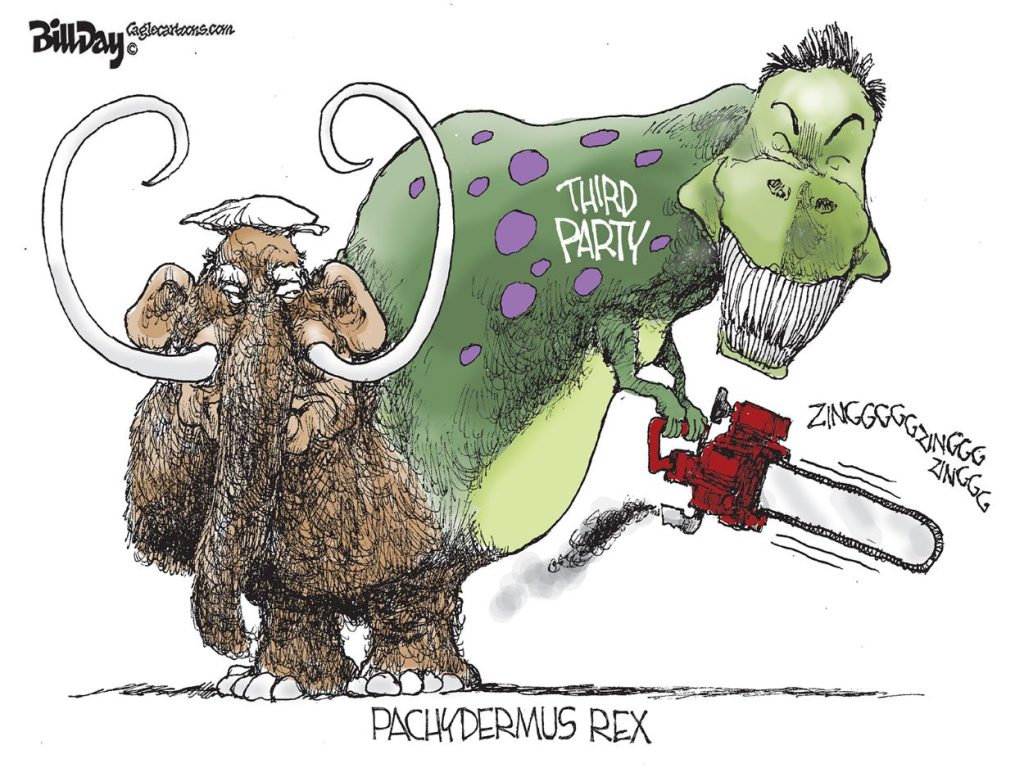

So, for those of you who have been following the rather unbelievable battle in Memphis between the Memphis Zoo and the Overton Park Conservancy over what I call automobile storage on the park’s historic lawn, an old-fashioned headline could be: “Zoological Park Treats Park as Car Park.”

While advocates struggle mightily to create new green space through precious parcels here and there, a large swath of existing parkland is given over to automobile storage. In a study, we did in 2007 we found that collectively 70 major city parks in the United States devote a total of 529 acres to the very technology that many people seek to escape when they had into their local patch of nature.

There are three ways to reduce the problem of car storage in city parks. Naturally, none of them is painless. As Jeff Vega, longtime head of New Brunswick Tomorrow says, “If you don’t find resistance, you aren’t doing your job.”

Parking Options

The most effective response is to charge a parking fee. Storing a car in a park is a service with value to the driver. It also puts human environmental costs onto the park. A payment makes sense.

Most of the high population density cities don’t try to meet all the auto demand, relying on residents to walk, bike, use transit, or pay to use private garages nearby. Most of the low-density cities don’t get enough usership in any one park for it to be overwhelming. The mid-density city is where the issue often comes to a head. Minneapolis has taken the lead in charging for cars, probably because it has an independent park board that can set its own fees and is somewhat free of traditionally city council politics.

The flip side of the coin, of course, is to provide park users with transit options. The third approach, as I’ve already discussed, is to gradually increase the density around parks. This is the most incremental, but it is also the most permanent.

In every city, there are hundreds of acres of streets and roadways potentially available as park and recreational facilities. Converting some street capacity for recreational activity – either fulltime or part-time – is an under-realized opportunity. Or as landscape architect Ignacio Bunster-Ossa says, “I think of highways as a form of land banking.”

Looking Ahead

We came to realize that the overriding health principle is that the park must be used by the public. This is not a platitude. Not all parks are well used. Not all advocates and not all park managers want their parks to be well-used. (Our note: we immediately thought of our zoo.)

The more facilities and discrete spaces that are layered onto a park, the more use it can get from people with different interests and skills. Same with programming. Good programming can increase park use many times over, make activity more enjoyable, and increase its provision of health and fitness.

I want to look to the future – at least the future of the Center for City Park Excellence. What are we thinking about?

* The relationship between park creation and housing creation.

* The relationship between park departments and those social service agencies that are working with the disabled.

* The value of parks to not only to housing prices but also to commercial building values.

* Public parks on public rooftops.

* Sports that involve more people on less space, like volleyball, pickleball, and disc golf.

* Cemeteries with park benches, concerts, and maybe off leash dog runs.

* How exactly new parks are paid for and created.

* The pros and cons of splitting apart park and recreation departments.

* The pros and cons of making developers pay park dedication fees.

* The role of Business Improvement Districts with parks.

* A comparison of the underlying wealth of each city and the amount that it spends on parks.

There are many problems in the U.S. today, but I think we can honestly say we are coming into a golden age for city parks.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.