This article three days ago in the St. Thomas Source in the U.S. Virgin Islands is the latest reminder of why there is no defensible reason why Memphis should be forced by state government to keep Nathan Bedford Forrest’s grave and statue in a city park.

The article was printed below the headline — Nathan Bedford Forrest: American Terrorist.

If you believe in American exceptionalism, it is hard to find a box to put Nathan Bedford Forrest in. If you also believe that greatness and goodness somehow go together, it is even harder to deal with Forrest. By almost any measure, Nathan Bedford Forrest was an extraordinary leader of great intelligence and remarkable courage.

But, unless you believe in unrestrained racism, almost everything that Bedford did was morally indefensible. The great bad person. Napoleon comes to mind, but without the positive achievements that we associate with him. There are no codes of law or magisterial public works. Just lots of dead bodies

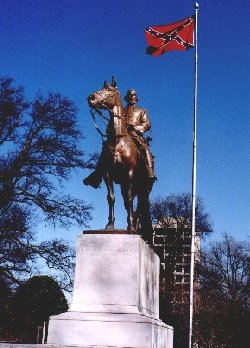

But, like Napoleon, whose many monuments can be found in France, Nathan Bedford Forrest has been memorialized. There are schools named after him and a giant statue of Forrest on his horse surrounded by confederate battle flags. In certain places, July 13 is celebrated as Nathan Bedford Forrest Day. At one point several years ago, the State of Mississippi considered issuing Forrest license plates. All homage to the great man.

Who was Nathan Bedford Forrest, and what were his achievements? Forrest was a man of limited education. Nevertheless, he had become wealthy in the pre-Civil War south as a slave trader and plantation owner. When war broke out, Forrest quickly joined up to throw himself fully into two of the causes that he most fervently believed in: slavery and killing black people.

Forrest enlisted in the Confederate army as a private. By war’s end, he had been promoted to Brigadier General. President Lincoln’s problems with his generals, especially early in the war, are well known. Less well known are the deficiencies of the Confederacy’s senior officers, which drove Jefferson Davis to distraction. Forrest was not one of the deficient ones. He proved himself a brilliant tactician, an innovator, a man of strong personal courage and a strong leader.

At one battle, Fort Pillow, Forrest captured a large number of black soldiers. Rather than taking them prisoner, his troops massacred them. The result was an end to prisoner exchanges between north and south. As the war turned against the South, Forrest became a master of guerrilla warfare, harassing Union forces and provoking General Sherman’s brutal “March to the Sea.” Forrest made his last stand at Selma, Alabama, escaping by leading another massacre.

With war’s end, as chaos, terrorism and lawlessness descended on the South, Forrest again became a leader. He became a founder of the Ku Klux Klan and sought to rebuild his businesses. One of his goals was to convince the newly freed slaves that they should return to slavery. In this respect, he again became an innovator. He pioneered what Douglas Blackmon has called “slavery by another name,” when, in 1871, he bought the “contracts” of 241 “leased out” black prisoners, giving him an important role at the dawn of what would become the prison industrial complex.

In our times, Nathan Bedford Forrest, like those confederate battle flags that frame his statue just off Interstate 65, has become a source of conflict. Demands are made for the removal of his name from schools or of statues in his honor. Southern conservatives – and some of their northern friends – resist these calls as an attack on their “heritage” or just more “political correctness.”

Some point out that Forrest quit the Klan and made conciliatory statements about protecting black lives. This is where the consequences of our tangled racial history move into a parallel universe, one in which monuments to a slave trading, slave owning, murderous founder of the Ku Klux Klan are actually there to honor him as a kind of an early civil rights leader, and that Southern “heritage” has nothing to do with race.

Like other topics in our shriveling historic and political discourse, there is not much basis for a reasoned discussion there. To usefully employ one of the more useless phrases of our times, it is what it is. He was what he was.

Editor’s note on the use of terms. In this series, terms are used in a very specific manner.

“Racism”/”racist” is limited to examples of what has been defined as “scientific racism,” the belief that one race is inherently superior/inferior to others, and, the current use, a power relationship in which one group dominates another, as in “white supremacy.” Racism in this context is typically a system.

“Bigotry” is used to describe group or individual beliefs that stereotype or demean another group. In this sense, bigotry is not limited to the group(s) that wield power over others.

“Racialism” is a term that describes practices intended to pit groups against one another, even in the absence of the individual being a bigot or racist. Racialism is widespread in our political life. For example, in 1964 Barry Goldwater ran ads with a picture of a white worker (“fired”) and a black worker (“hired,”) while in 1980, Jimmy Carter implied that Reagan would re-enslave black people.

(Thanks to George Lord for sending article.)

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

they should really stick to fleecing tourists down there.

One of the better articles I’ve seen on this topic. Our city monument to Forrest in a high traffic tourist zone is offensive, insulting and embarrassing. That some citizens see the statue as proud heritage is mind boggling. I feel mortified every time I pass the offensive thing.

Well it truly “is what it is”. So we just need to live with it since its part of our history. Much bigger fish to fry in 2017 with Trump in power.

It is in normalizing Forrest that we paved the way for Trump.

It seems to me the only people concerned with this are the handful of people that just won’t let this issue die. The vast majority of people couldn’t care less, and don’t even think about it as they drive on Union or Madison. It’s truly time to turn our attention to the issues that are affecting our present day city. Unfortunately we tend to focus on the low hanging fruit of trying to make the past more palatable to our tastes of today. That’s oh so simple, but doesn’t address any of the current days issues which many people, including our current Tennessee State Legislature, are cowards for not addressing. I guess we’ll all be looking at changing the name of Watkins street, or Overton high school soon since the person they were named after, Memphis Mayor Watkins Overton, was a self proclaimed segregationist.

Agree with Anonymous and John Doe.

99% of all people just don’t care about trivial things like this.

The history of our country, including the history of the south, is filled with dark events and with deplorable leaders.

Especially so today with Trump. Time to move on from this and leave ole Forrest to Rest In Peace in our city park.

I’d love to replace the Forrest statue with a large water fountain perhaps something like Chicago’s Buckingham Fountain. Give us an actual reason to go to the park in the summer, especially the thousands of workers in the medical district. By the way, southern conservatives are not monolithic. The statue is an ugly distraction.

So, you admit that he represents a dark event and deplorable leadership, but you think our city should have to maintain his grave and statue and that a city park should be wasted on him. Get real.

John Doe:

The statue was moved to the park from a cemetery. That makes it different. It was a deliberate action to show black Memphians that the city leaders refused to let go of their Confederate, racist opinions.

And it doesn’t matter if there are more important things to do. We can chew gun and walk at the same time, and as this article shows, it affects how we are perceived by others. Time to put him back in the cemetery.

Like him or not, Forrest has an important place in the history of Memphis and of the south. I have no issues with this statue, grave or park. It should serve as a reminder to all of our past and of just how far race relations have (and have not) progressed in this city.

We’ve written about the absurdity of honoring Forrest in a city park, and the intrusion of state government in a decision that should be made by City Council. This statue does nothing to illuminate the insidious institution of slavery and it does nothing to remind us of how far our city’s race relations have come. There are many, many more ways to do that without offending the majority of Memphians and in a way that does not on its face look like a tribute to the misplaced values Forrest fought for.

A large water fountain in the park would be grand but don’t you think we need to accomplish other more essential things like fixing the long broken trolleys, putting more police on the streets, cleaning up blighted properties and generally trying to combat our out of control crime and helping out our failing schools?

Anonymous: Why exactly is this either-or? How about all of the above?

It really makes a lot of sense for modern Republicans to passionately defend Forrest, a lifelong die-hard Democrat. Right? Right? Anyone?