About a year ago, Tim Bolding’s 91-year-old mother died, which put her 61-year-old son into a reflective mood about his priority for the next chapter of his life.

After working more than three decades to provide affordable housing for Memphians frozen out of the traditional mortgage market, it was no surprise that his thoughts turned to his career’s purpose, but one term became top-of-mind — game changer.

“It was about doing something now,” he says. “I can’t wait. Neighborhoods can’t wait. Memphis can’t wait. It was about a big idea that would be system-changing.”

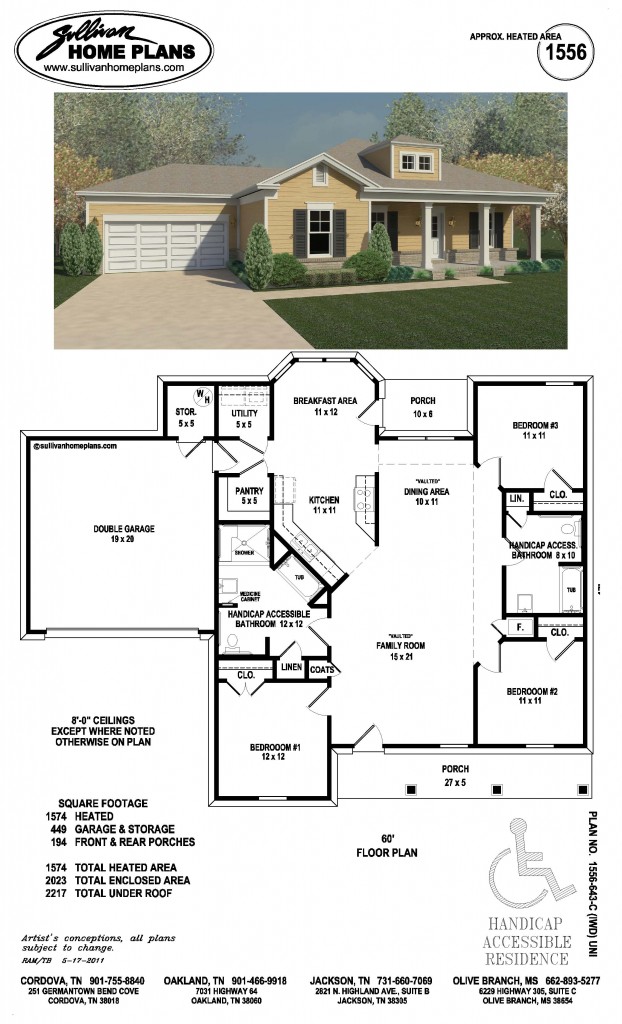

He calls his “big idea” the Memphis 10-K Housing Initiative, a plan to build or rehab 10,000 houses in the next 10 years. No one knows better than he does just how big that idea is. After moving from Nashville to attend the University of Memphis, Bolding’s housing experience began in Shelby County government and continues as founding executive director of United Housing Inc.

500 Credit Neighborhoods

In his 22 years at the helm of United Housing, the nonprofit group has provided 4,469 affordable houses for families who otherwise would not be homeowners. And along the way, Bolding has become an expert about the barriers blocking too many Memphians from home ownership.

“There are tools for multifamily projects — Tennessee Housing Development Agency, Low Income Tax Credits, PILOTs, low interest bonds, and more,” he explains. “There is a whole industry built around these tools. But for single-family houses, it’s all about the tools we don’t have available in many neighborhoods.”

He pointed out that there are always builders, financing, appraisers, and real estate agents for “700-credit-score neighborhoods,” but in “500-credit-score neighborhoods, the system is not a system.” This in turn contributes to population declines, thousands of boarded-up houses, shrinking tax revenues, and tens of thousands of houses already seized for nonpayment of taxes.

“It is a deep wound for Memphis,” says Bolding. “The loss of property owners has been dramatic. The building industry has been decimated in the last 20 years — from 350 builders to 20. There used to be 5,000 houses built in a year and now it’s 500, and at the same time, population is down and we have thousands and thousands of vacant lots.”

Signs of Progress

The plan for 10,000 houses is his response to these problems, and it’s all about creating a system for “500-credit-score neighborhoods,” so the private sector will want to develop and invest there.

United Housing’s Wolf River Bluff development at the end of McLean Boulevard north of James Road suggests that it can be done. Twelve houses have been built on a tree-lined street, with solar panels, public art, walking and biking trails, and all are adjacent to an 11-acre Memphis park. The houses sell for $129,900, appraised at 100 percent of sales price and sold without government financial incentives.

Meanwhile, homebuilders and developers like David Walker of Vision to Reality LLC are proving that new homes can sell in urban neighborhoods where it did not previously seem possible.

“Buyers will come if a system is in place and if the product is what people want,” says Bolding. “If we have the right tools, everything is possible. Binghampton is doing so much good work. The same for Crosstown and Soulsville. Imagine what they could do with the right tools for single-family housing.”

Getting Off The Roller Coaster

These include down payment assistance for buyers, rehab financing, developer infrastructure assistance, and loan loss reserves to reduce risk for private financing. Also, homebuyer education and financial counseling which are critical, because “the city is full of people who need help but are not ready to be helped.”

The 10-K Housing Initiative costs $140 million, with almost half coming from state and federal agencies. An economic impact report concluded it would produce a $2.9 billion infusion into the economy; 2,100 jobs, and $150 million in new city and county property taxes.

So far, the “big idea” has attracted interest from local and state government, philanthropies, financial institutions, developers, and homebuilders. And if it comes together, it could end what Bolding calls the “roller coaster” of building and rehabbing houses in lower-income neighborhoods because of inconsistent funding and lack of a long-term plan.

He believes everyone with a stake in a better system will come together to design the tools needed to make it work, and then develop an organization to organize and manage the 10-K Memphis Housing Initiative.

In the end, Bolding says: “This isn’t a United Housing plan. It’s a Memphis plan. If we make it a priority, we can do it.”

Previously published in the January, 2017, issue of Memphis magazine.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

Be careful singing the praises of United Housing. They have bought several homes in my neighborhood and have sold some of them to SRVS, thereby depleting the available housing stock of single family homes.

If Tim Bolding needs to advertise those homes at some point – we can handle the photography &/or TV spots, video for websites etc.

Welcome to Memphis: 228 homicides in 2016,” say the new highway billboards, reminding this crime-weary city the police force once had 500 more officers.

Memphis Finest and Anon:

And your point would be…?

Perhaps you mean that entrenched poverty and lack of support for public education lead to desperate people with no hope and therefore nothing to lose?

Or perhaps that generations of institutionalized racism (yes, I said it) continues to contribute to increased income disparity?

Or possibly you mean that more than 60% of the homicides you cite occur in low-income neighborhoods, and that an additional 30% are domestic, meaning that the real occurrence of random crime is much smaller than its perception among frightened non-urbanites who have little experience living in or enjoying the actual city?

People like Tim Bolding, and SCM for that matter, are doing their best to make a positive difference in Memphis. It’s a tough undertaking. They won’t always be perfect. Nevertheless, they deserve our help and support. For those who disagree, or who simply hate Memphis, there are plenty of other places to move to.

Thanks for that response The facts are inconvenient things, especially when it comes to the police union.

As for us, the fundamental question is whether we need 500 more police officers. How exactly could the union explain that it would reduce the number of murders? And how exactly does it make sense that the union should traffic in fear when it needs the public to have as much confidence as possible to support them. It’s time that we think of answers that isn’t about more firepower and militarization.

can pantoprazole cause diarrhea nukusoki44-domperidone how to boost milk supply while pumping

can you lactate when you re not pregnant sokukeru49-tumblr calculate molarity of hcl