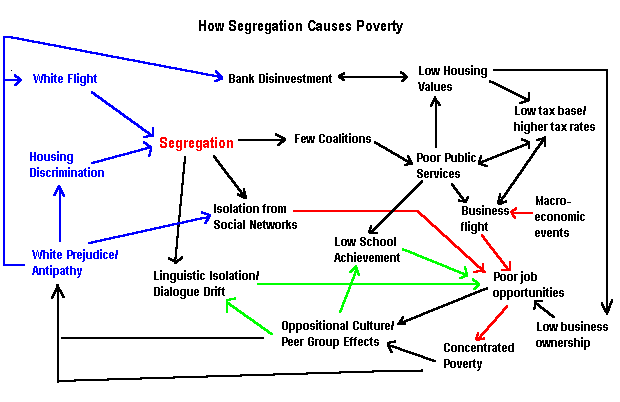

(University of Michigan chart.)

In the wake of recent events in Milwaukee, income and economic segregation there have garnered national headlines. This is a deep structural issue in the Memphis MSA with serious implications to our economy, our quality of life, and our commitment to the American dream. We should not watch things unfold in Milwaukee and say that it can’t happen here and things are different here. Memphis and Milwaukee share underlying characteristics and we should look to that Wisconsin city as a cautionary tale.

****

As PolicyLink’s National Equity Atlas says: “Cities are equitable when all residents – regardless of their race/ethnicity, nativity, neighborhood of residence, or other characteristics – are fully able to participate in the community’s economic vitality, contribute to its readiness for the future and connect to its assets and resources.”

That’s the obvious goal for Memphis. Unfortunately, economic segregation is the reality.

We All Lose

Memphis, both the city and the region, have too long fought problems, conditions, and lost opportunities that stem from the way that economic opportunity is always out of reach for too many people locked into neighborhoods of concentrated poverty. If the structural problem wasn’t difficult enough, the sprawl of the past 40 years has exacerbated the problem as it festered into economic measurements that are doggedly difficult for Memphis to turn around.

Put simply, every problem becomes harder to address because of economic segregation.

Research by Harrison Campbell, associate professor of geography at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte, proves what Memphis has experienced. He has concluded that when segregation is high in metro areas, those places’ economies perform worse when compared to places with less segregation. More to the point, segregated regions have seen lower rates of income growth and lower appreciation of property values.

Here’s the kicker: the impact isn’t just felt by African American and Latino families in segregated areas of concentrated poverty. It’s also true for everyone, regardless of where they live: neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, the urban core, the city as a whole, the suburbs, and the entire region.

We All Win

A common question asked of Professor Campbell is how exactly does the segregation of poor African American families drag down the economic opportunities for college graduates working in job centers on cities’ fringes. His conclusions is that as the spatial mismatch of jobs continues to get worse, and as employment opportunities sprawl, people in segregated cities are isolated more than ever. But this doesn’t just create problems for low-wage workers. It is also bad for people with good-paying, high-skilled work, because economies rely on labor of all kinds.

This spatial issue is compounded in cities like ours – which is #1 in the ranking of the top 50 cities for the places where people pay the highest percent of their median household income in transportation (27.3%) – and when job centers and office parks are located beyond the reach of public transit, as they are here, the inefficiency of the region’s development pattern starts to affect the region’s economy as a whole in a negative way.

As Professor Campbell posits, when poor people have more and better access to opportunity, besides the obvious economic benefits, cities can reduce their costs of to address poverty and the web of problems that spring from it.

All in all, it makes the case for how out of kilter our funding priorities are in this region and why over the past 20 years, economic segregation deepens.

The darker the green, the lower the income.

Public Transit Matters

Mr. Campbell’s suggested solutions:

1. Subsidize housing so low income people can live closer to jobs

2. Stimulate jobs in areas where poor people live now

3. Better connect poor people where they already live to jobs where they already exist

Of the three, he believes that improving public transit is the priority. “It doesn’t require state or local governments to pursue economic development policies that try to direct jobs to certain places,” he says. “It doesn’t upset housing markets. It doesn’t upset suburbanites who may not want housing that is part market-rate, part-subsidized. It just allows people to be more mobile.”

Getting To The Right Questions

Herein lies the greatest challenge to all of the new commitments made by new partners to attack poverty. So far, many of the ideas are ones we’ve heard before, but what’s left unspoken is the need to find the answers to these core questions: What would a high-performing public transit system in Memphis and Shelby County look like, and when do we get serious about adequately funding MATA to make it happen?

To answer these questions assertively is not merely an act of morality, charity, or empathy. Most of all, it is an act of enlightened self-interest.

Now, if anything, we need for Memphis and Shelby County to enter its Age of Enlightenment.

Next Post: Data Points – Segregation

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.