We’ve been re-reading one of our favorite histories of Memphis – Memphis During the Progressive Era 1900-1917 by William D. Miller (1957) – and we’re always struck by how some character traits of our city were apparent so many years ago and how their currents run through our history just as powerfully as the currents run through the river at our front door.

There are the envy of other cities, the selling of Memphis on the cheap, concerns about public safety and one of the nation’s highest murder rates, complaints about inadequate public transportation (street cars), the lack of attention to the needs of poor African Americans, the commodities approach to economic development, the need for more voter engagement, the lack of money for major investments in quality of life, and more.

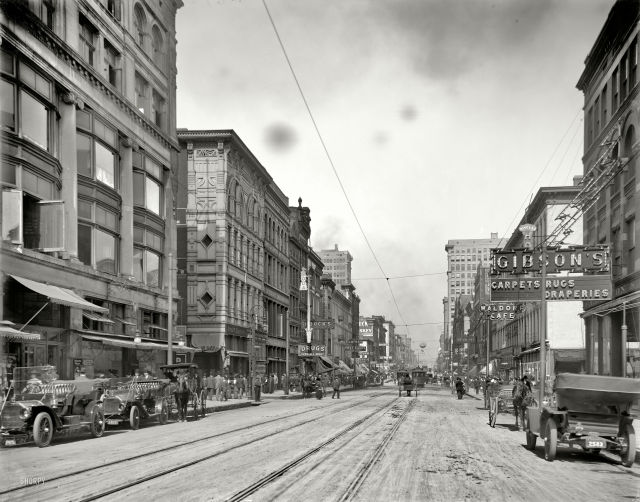

The good news is that during the Progressive Era in the United States – it was never called the Progressive Era in Memphis but rather was considered a time of reforms – this city was considered a leader in progressive policies, ranging from its standard-setting sewer system, its plan for parks and parkways, public ownership of the water company and movement to do the same with electricity and street cars, the beginnings of the zoo, improved street car service (they finally got rid of the mules), and a modern plan of road construction to replace the mud roads that passed for major thoroughfares and the deep holes and ruts that capsized unwary drivers (and even led to the report of a mule drowning on Main Street).

We’ve written previously about Memphis’ role in the Progressive Era so that’s not the purpose of this post. Rather, it’s about threads that seem to bind together the history of the city.

Commercial Appeal, April 25, 1900, selling Memphis at a discount:

The major benefits being marketed for the economic growth of Memphis were the docility and cheapness of Memphis labor. “Memphis can save the Northern manufacturer…who employs 400 hands $50,000 a year on his labor bill. Our advantage is the Negro…and there is no race problem at all.” The Business Men’s Club, soon to become the Chamber of Commerce, added: “Practically all Memphis labor, whether white or colored, is all American…Such conditions make for loyalty on the park of the employees to the government and to their employers.”

Commercial Appeal, September 27, 1901, about pistol packing Memphians:

Pistol-carrying was prevalent in Memphis. “Everyone in this community who wishes to do so carries a pistol. The enforcement of the law against pistol-carrying in this country is such a farce that nobody hesitates to go armed…Today the condition of affairs is worse than it was 20 years ago…There never was a time, unless it was immediately after the war, when the carrying of arms was as prevalent as now.” The pistol-carrying resulted in a number of murders on city streets in “pseudo duels” fueled by more than 500 saloons, numerous gambling houses, and ubiquitous brothels.

The Commercial Appeal, September 20, 1900, on the end of the bicycling fad:

“There was never a city more cycle mad than Memphis. Everyone owned a wheel then and it was considered the proper thing among the smart set to ride bicycles.” When “society realized that its poorer sister and brother were riding on the same boulevards, drinking and lunching at the same road houses and refectories – one by one…they took up golf and other stylish sports.”

The Commercial Appeal, August 27, 1902, concerned about impact of automobiles:

“The rapid gait of the automobile is apt to cause many runaways and much damage to life and property…We can very readily imagine the day when the farmers and country people will repel this danger just as did their forefathers the perils of the wilderness..A few catastrophes and those who have suffered will get their guns again and will treat the automobile as their forefathers treated the panther and the bear.” The following year, there were 40 automobiles in Memphis.

The Standard History of Memphis, J.P. Young, 1912, writing about the purchase of Lea’s Farm for what would become Overton Park:

“Rare wild plants, vines, grasses and flowers spring up in bewildering luxuriance and infinite variety to attract the scientist and lover of nature and where children can roam next to Mother Earth and her own immediate handiwork, as in the days of our first parents…Trees that were here when DeSoto came rear their mighty heads at intervals, and one buried in the great wilderness can discern no evidence that despoiling civilization exists anywhere near.”

The Commercial Appeal, July 18, 1902, expressing its concerns about modern women:

The “social education of the modern girl has been woefully neglected if she has not even a speaking acquaintance with golf.” The “indoor athletic girl” playing ping pong presents a charming pose “with her skirts held tight in her one hand, while she plays with the other…(paying) particular attention to the frills on the bottom of her frock, and on her petticoats, for they will show and be very dainty and chic on the reverse.” Sports participation by women is “a symptom of declining gentility, of the new, rude, free ways unaccountably attractive to the young.”

The Commercial Appeal, October 1, 1902, on the superiority of the South:

“A certain aloofness and lack of devotion to commercialism during the last 20 years of its growing ascendency in the national life, coupled with that temperate addiction to business which has ever characterized Southern peoples, have kept this portion of the United States from falling into a contemptuous attitude toward intellectual and social interests…There are not as many professional reformers in the South as in the North, because the superior solidarity of the people of this section minimizes the evils of civilization and renders the contrasts of life more endurable.”

The Commercial Appeal, September 18, 1898, supporting the “Greater Memphis” movement and annexation of Idlewild and Madison Heights:

The people opposing annexation are unwilling to pay for the healthier community they would gain and if annexation were thwarted, it would result in suspension of work on sewers and leave the city unprotected from invasion of disease.

The Commercial Appeal, January 23, 1903, criticizing public transit:

The street railway service was “two lines of rust no much larger than a lightning rod, between which was a tow path of gravel or a series of planks” and along which ran cars pulled by “an industrious little mule with the tingling sheep bell handing from its hame strings.” As a result, a trip across the city was an adventure wince a traveler could never predict when or in which condition he’s arrive at his destination.

The Commercial Appeal, April 6, 1906, quoting Judge L. B. McFarland’s call for a modern park system, including a proposal for a park for African Americans on President’s Island:

“The Negro park question is forever solved.” While the land floods, “the overflow comes at a season of the year when people do not care much about going to parks. When the water subsides, there is a rich alluvial deposit left, which accounts for the rich luxuriant growth that covers the island. The Negro ought to be in his glory among all that tropical growth.” Eventually, land outside the city limits near Macon Road was purchased and became Douglass Park.

The Commercial Appeal, on Memphis’ crime problem:

May, 7, 1907 — “Dives have been flourishing as they have never flourished before. Hundreds of lewd women, equipped with vials of chloral and knock out drops, have been imported. Street walkers have been as thick as wasps in summer time.” Brothels were located throughout the “Tenderloin” district and concentrated on Gayoso Street, center of the red light district.

March 3, 1909 – Murder is the “most thriving industry” in Memphis. “They kill them next door to City Hall and shoot them in park.” News boys cry “All about the big murder,” but “every day is murder day. Some day if he (the news boy) should go out and cry, ‘Not a man killed in 24 hours in Memphis territory,’ he might do a bigger business.” In 1910, Memphis had 105 murder, and in 1916, there were 134, when Memphis had the highest murder rate – 89.9 homicides per 100,000 people – of any city in the U.S. “What with the delays of the law, good lawyers for the defense, inefficient criminal methods in the courts, barbarous laws for the selection of juries, the murderer is in less danger of hanging than is the average pedestrian in danger of being hit by a stray bullet.”

National Audit Company, October 10, 1903, on its audit of city government after the mayor finally allowed the city’s books to be examined:

There is a “general lack of system in the accounting methods of the City, each department apparently being managed according to the offer in charge.” The Morning News wrote that the “methods of conducting the public business such as would bankrupt any private concern on earth in the course of a few years. “ It also pointed out that the 14-year-old son of the mayor was on the city’s payroll as a sewer inspector.

The Commercial Appeal, March 1, 1911, on Mayor Crump’s crackdown on crime:

The police department has “improved in appearance, in efficiency, and in courtesy during the last year. The officers are smarter, are neater in appearance, and do not look as if their time was spent chiefly in loafing around saloons.” Arrests were up about 66%, transients were rounded up, and any African American found on the streets after midnight was arrested.

Commercial Appeal, August 22, 1909:

In looking back at 1900 Memphis, the CA wrote: “Main street virtually ceased at Beale on the south and Poplar on the north. There was not a decently paved street in the city. Main was paved with cobblestones…Second street was an avenue of mud and slime…Rotten Nicholson pavement was prevalent nearly everywhere.” Three years earlier, Ladies Home Journal had printed pictures, “Eyesores That Spoil Memphis,” and one showed that the land between Front and the levee was used as a dump for broken down wagons and used packing boxes, which spoiled views of the river from Cossitt Library, and there was another dump behind the Grand Opera House.

Memphis During The Progressive Era’s summary by author William D. Miller:

“Progressivism had brought Memphis better water and sewage systems, better streets, better fire and police protection, and a handsome network of parks and playgrounds. It had reformed the courts and penal institutions, improved the school system and laid the foundations for an effective public health program. The city government had stood up to the corporations and had brought a measure of order to the city’s economic life. Through the establishment of a commission form of government, the city had achieved a more mature political leadership and a more efficient administration. Existing institutions had been reorganized and new ones developed to deal more effectively with many of the social problems of the time.

“But the failures of the progressive movement in Memphis were as apparent as its successes. Public health was far from achieved. The saloons and prostitution had been only spasmodically curbed. Violence and lawlessness persisted – the murder rate rising to a peak in 1916 – as evidence that the social disorganization of the city was by no means straightened out. The Negro was actually little better off than he had been in 1900. And in spite of governmental reforms, the city had not ended bossism – a feat that could have been done only through the growth of a critically minded self-informing electorate.”

Originally posted September 25, 2015

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.