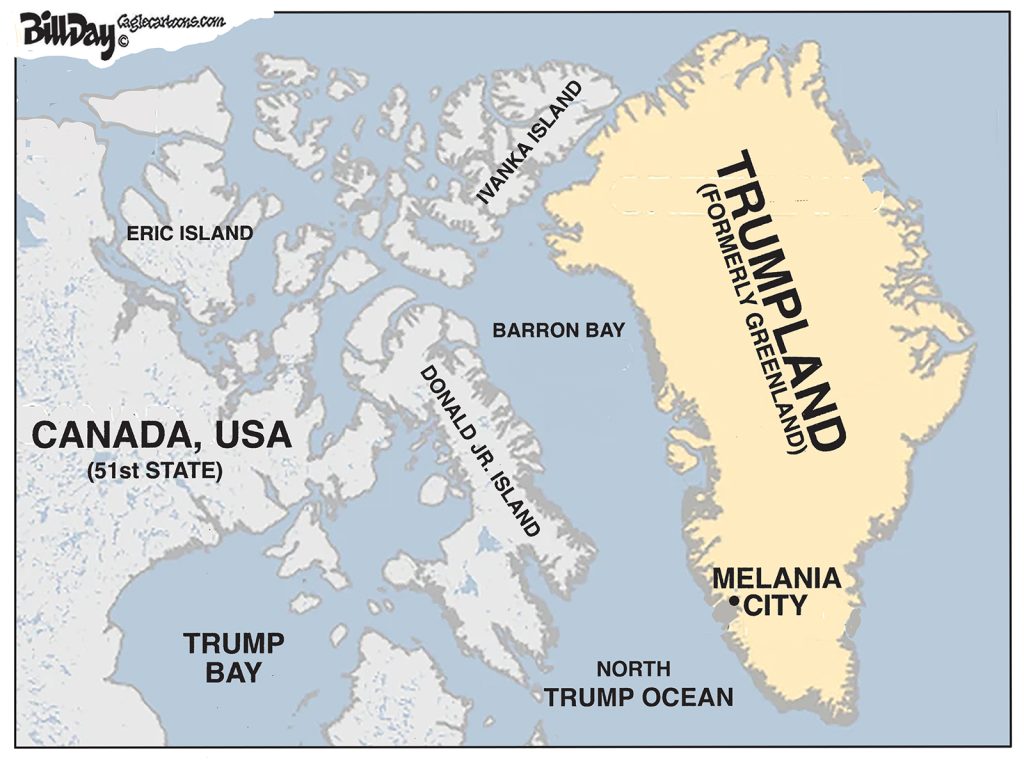

With the movement by City of Memphis to move Nathan Bedford Forrest from a city park to the cemetery brings to mind the Confederate detritus populating downtown’s Memphis Park. It’s time to clear that park with the random remnants of Confederate pride. If we indeed keep Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America and Memphis insurance company president after the Civil War, in the park, we’d like to make a modest suggestion: we should decorate the statue for holidays. We think the image of Jeff Davis festooned for the Fourth of July would be an ironic, and delightful sight. Or for Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, and other special days. If he is to be there, let’s add some some fun-loving decoration activities that put him into his proper place in modern day Memphis.

The statue has only been in the park since 1964, as John Branston wrote in 2013 in The Flyer.

Here’s our blog post from July 17, 2015:

Removing A Confederate Attic From Downtown’s Memphis Park

Now that we are intent on burying one racist artifact by sending Nathan Bedford Forrest back to the cemetery and shipping off his statue, can’t we also throw in the statue of Jefferson Davis in a downtown park as part of the deal?

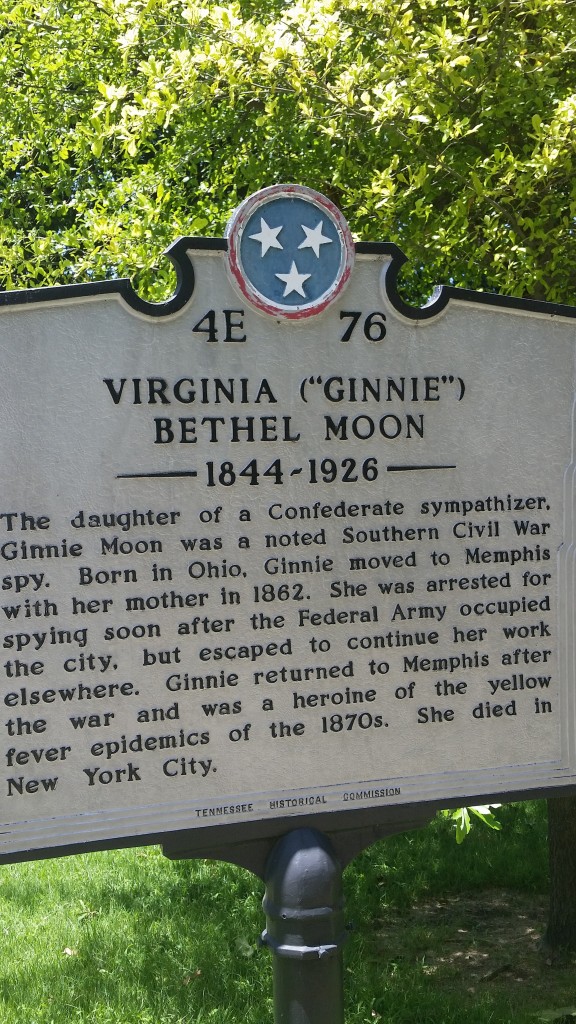

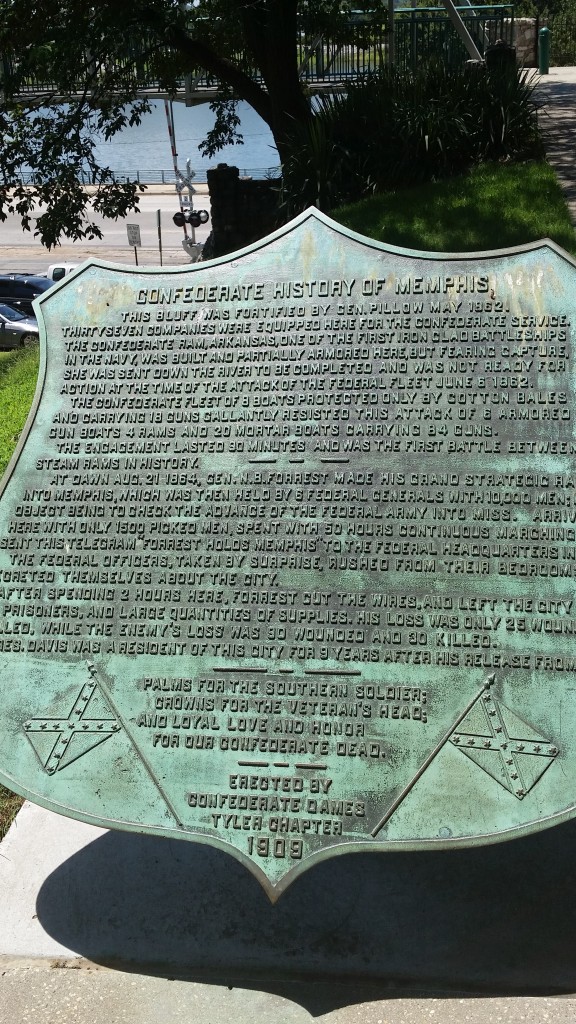

While the park has a new name – Memphis Park rather than Confederate Park – it still acts as the Rebel attic for a hodge podge of Confederate tributes, including the statue of the first and only president of the Confederate States of America. While most of Memphis’ Jim Crow monuments were put in place shortly after the 20th century began, the Davis statue was not erected until the 1960s, apparently as a direct response to the growing power of the civil rights movement.

It’s a troubling reminder of the hostility and hatred tha lay at the heart of decisions to honor and keep honoring soldiers fighting to maintain an economy built on the backs of slave labor at slave labor camps, plantations painted over time with a brush of sentimentality and fiction.

It could almost be humorous to watch the pretzel logic exhibited by the defenders of the Confederacy, ranging from the South wasn’t really fighting for slavery, it was fighting for state’s rights (true, the right of the states to have slavery); the battle flag is just a tribute to the courage of these brave soldiers (in the same way the swastika is a tribute to the courage of German soldiers), and these are our relatives and we don’t want them to be forgotten (our relatives also served in Confederate uniforms but we remember them as members of our family, not as heroes (since it’s hard to work around the fact that they were fighting so people could remain property).

No One’s Laughing

But it’s not remotely funny. These monuments are ugly reminders how those in power use their privilege to humiliate minorities, to pass laws that prevented black Americans from accumulating wealth, and to praise those who would have destroyed the United States as we know it today.

Strangely, in listening to the flimsy defenses of Confederate monuments, it is easy to come to conclusion that the defenders see themselves more as descendants of Confederates than as citizens of the United States, and as a result, they made the conscious choose to perpetuate the divisiveness of the Civil War and make their lives’ purpose the elevation of a lost, traitorous cause until it has no resemblance to the facts.

Apparently, it was in the pursuit of their revisionist history that someone in 1960s audaciously carved the following into the downtown statue of Jefferson Davis: “He was a true American patriot.” That the statue was erected in the same era that saw Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder in Memphis, and that even today, we have no statue of Dr. King speaks volumes on the power structure and its motivations at the time.

The statue was placed downtown six decades after Confederate Park was created – at roughly the same time as Nathan Bedford Forrest was buried in the Medical District park and a statue was added as a cherry on top.

Thumb In The Eye Of Unity

A friend told us this week that in a history of Memphis that he was reading recently, the explanation for Forrest Park was that in the first few years of the 1900s, Memphis had gotten its balance back after the devastating yellow fevers in 1878 and 1879 that resulted in 30,000 of the 50,000 Memphians fleeing the city. Of the 19,000 who stayed, 17,000 came down with yellow fever and 5,150 died.

Prior to the yellow fever epidemics, Memphis was home to large numbers of middle and upper middle families and a substantial underclass that has characterized it from its earliest days. During the epidemics, people with means moved, and by the end of the epidemics, it was poor African Americans, Irish, and others without means who were left here. (In fact, some of the “old” families in Atlanta, Nashville, and Cincinnati whose roots run to Memphis.)

With the dawning of the 20th century, the cause of yellow fever was determined, the city gained notoriety for inventing the modern sanitation system, and it started its road back. It is written that the city fathers wanted to drive a stake in the ground that said unmistakably that Memphis was back and that its future would be as a proud Southern city.

In that way, the Forrest statue and Confederate Park were ways that the message could be sent not just externally, but internally to let minorities know that although they had stuck with the city during its bleakest days, they should not get any big ideas that things had fundamentally changed.

Make The Park Worth The Trip

But that was then, and this is now.

If there is a place for the statue, the bust of Confederate captain, a history of Memphis during the Civil War, and a historic marker, it shouldn’t be downtown at the precise time that Memphis is trying to convince young professionals in particular that the city is not stuck in time or trapped by outdated, discredited historical events that have no relation to who we are today or the values that we have as a city.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

We may also consider doing something about Jackson Avenue through North Memphis where many Jackson Avenue street signs share their poles with signs marking the Historic Trail of Tears. Just sayin’.

Great point, Scott.

Move the Forrest statue to the pink palace where other confederate artifacts are already displayed. Somewhere on the grounds around the museum. You could do the same for Jeff Davis.