It’s a mantra heard for years by Memphis neighborhoods: We’d love to help but we don’t have any money and times are tough.

And yet, millions of dollars are given to profit-making projects and millions more are waived in tax freezes for private companies. Meanwhile, neighborhood leaders wonder if they can ever get to the front of the line when the money is handed out.

The Memphis economy, projected to return to pre-Recession levels at the end of next year, is finally rebounding and $4 billion in signature projects underscore that fact. City government gets little credit for its role in getting these projects off the ground in the form of tax abatements, direct appropriations, or financing mechanisms.

For example, Crosstown Concourse got a 20-year tax freeze waiving about $42 million in city-county taxes, but also $15.2 million from City of Memphis. The Chisca Hotel project got a $2 million check from City of Memphis to go with a 20-year tax freeze that foregoes $6 million in taxes.

The Tennessee Brewery got a 20-year tax freeze waiving more than $7 million in taxes plus $5.1 million from the Downtown Parking Authority for a parking garage and $2.5 million from city government. Most recently, City Council approved a $4 million loan/grant for a development at Union at McLean that also got a 15-year tax freeze that gives it a pass on $10.5 million in city and county taxes.

These are exciting projects, but it often seems that when developers are shown the menu of options for how city government can support them, they pick “all of the above.”

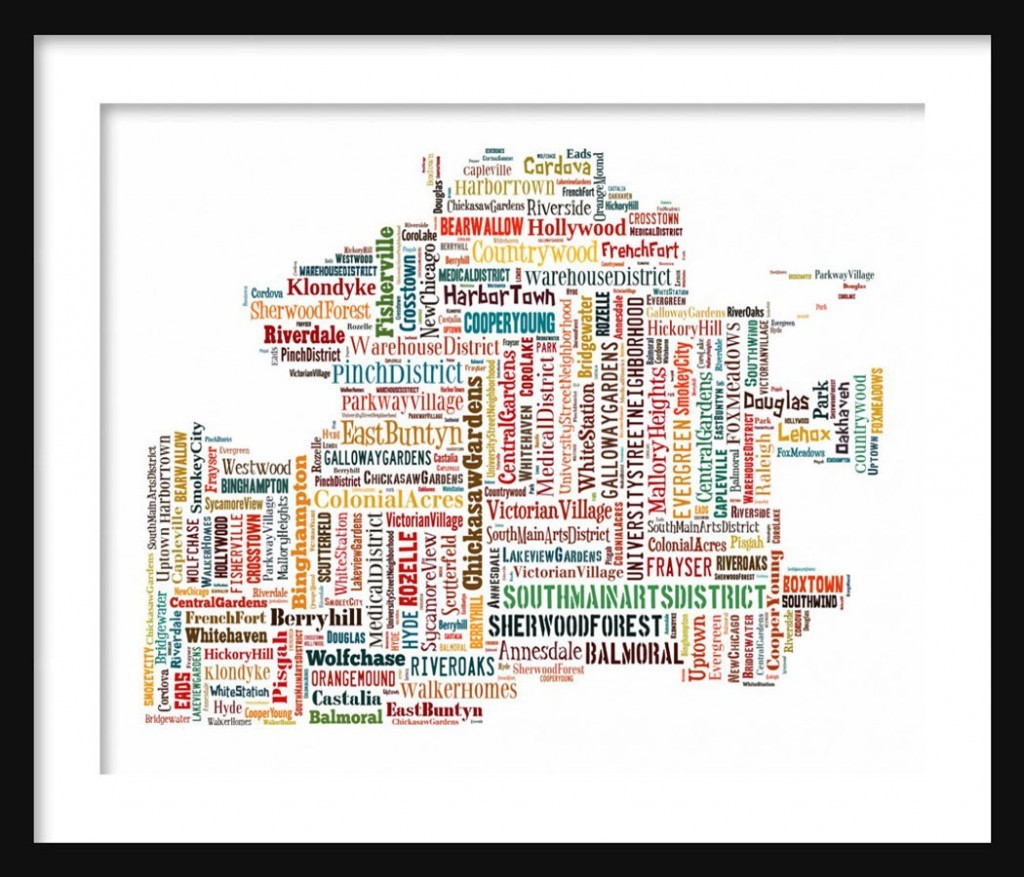

Redeveloping Memphis Inside-Out

At the same time, small-scale projects that could make a big difference in neighborhoods go wanting, leading activists to ask: If City of Memphis can approve funding, give away taxes, and issue bonds for big projects, why can’t it find money to help us?

City Council members at a meeting about Crosstown Concourse were told that as part of the work on that project, a plan to revitalize the Klondike/Smokey City neighborhoods to the north would be implemented. A slide presentation emphasized that “neighborhoods are the building blocks of community” and city government would “redevelop Memphis inside out, neighborhood by neighborhood.”

The high profile project got its money, but a City Council vote on the money to execute the neighborhoods’ plans has never taken place.

Neighborhood leaders took it as a hopeful sign when Mayor Jim Strickland called for his transition committee to focus on neighborhoods. Committee recommendations called for more direct city government involvement in identifying the needs of neighborhoods, creating measurements of programs’ impact, improving poor customer service, breaking down silos, and stimulating economic revitalization by creating stronger partnerships.

In addition, the committee said that “the City should establish and capitalize a new redevelopment fund comprised of city funds, private investment, grant funds, and other available national, state and local funds to assist non-profit and for-profit investors who seek to develop single family, multifamily and retail projects that will accelerate demand and investment in Memphis,” and “the City should partner and assist in developing a strong and independent community enterprise development entity that partners with the City and charged with facilitating increased urban revitalization for both commercial and residential areas.”

There is growing demand for greater attention to neighborhoods to build on the work of Memphis HOPE, Methodist Health Assets, Neighborhood Christian Center, Agape, LeBonheur’s nurse practitioners, GrowMemphis, Christ Community Center, BRIDGES, Caritas Village, Community Development Council, Community LIFT, neighborhood associations, and others.

Moving To The Front Of The Line

The transition committee said words matter, recommending that rather than talking about “blighted neighborhoods,” urban neighborhoods should instead be called “reinvestment zones.” As for the plan for the Klondike/Smokey City reinvestment zone, it remains on a shelf with other neighborhood revitalization plans waiting for a life line from City Hall.

All that’s needed for the plans and recommendations is money, but unlike many cities, city government puts no local money in the budget for neighborhood redevelopment. Instead, whatever gets done here has hinged on how much HUD funding is received by Memphis Housing Authority and Division of Housing and Community Development. With yearly declines in federal funding, city government funding will more and more determine if neighborhoods can be improved.

When city government talks about the need for a balanced budget, it’s referring to revenues and expenditures. But the budget also needs to be balanced between big projects and neighborhood improvements.

As neighborhood leaders say, it’s time for neighborhoods to move to the front of the line.

***

This was previously published in the February issue of Memphis magazine as its City Journal column by Tom Jones.

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

The city of Memphis provides loads of resources to help neighborhoods. Two two most basic tools are Neighborhood Improvement and the MPD. Neighborhood Improvement, under which falls code enforcement, ground services, and Memphis City Beautiful, is reasonably quick to answer any requests put to 311. Thing is, you have to use it.

The MPD non-emergency number, 545-COPS, is suitable for just about anything else.

Those two things alone can attend to most of the needs of Memphis neighborhoods. The more specific needs can be addressed through Neighborhood Watch Grants, simple local organization (as taught and reinforced through the neighborhood leader training program the city provides for free), and the city-wide drainage survey that is currently being conducted.

We have to be careful not to replicate too many services or we’ll find ourselves mired in redundancy.

Bravo!

Aaron: you are only looking at the maintenance side of neighborhoods. What is needed is the development side.

Neighborhood Improvement (Code Enforcement) is about complaints, blight, and dangerous conditions. This City agency is doing better than it ever has, but it is reactive, not proactive. Same with MPD. The Police Joint Agency initiative calls on neighborhood allies to identify problem properties and people. Again, it is only reactive and only dealing with problems.

What neighborhoods like Klondike/Smokey City need are developers and developments to repair and replace problem properties. This is turn creates jobs, trains residents, creates value, encourages stewardship, and improves a neighborhood. City Beautiful or the 311 system may clean up a lot or remove an abandoned vehicle, but only development dollars and deals can bring new life, new value, and ultimately new residents to an area.

It is woefully short to just clean up the mess; we have a city to build. Take a ride around K/SC and ask: who will repair these falling down homes? who will build on these vacant lots? who will do the hard work of changing empty lots into new homes and businesses? It is not Code nor the MPD nor CB. It is a developer like a Henry Turley (who brought Uptown out of the ashes), or an agency like Frayser Community Developer (who has created value for over 100 residents who were once renters and who now own rehabbed homes). These are the groups who need the millions of dollars and incentives that currently go to good projects like Union/McLean (Belz). But know well: these projects do help the poor areas of town. That’s where we need to be spending our public dollars and encouraging our private investment.

Aaron — what planet are you living on? Come look around Frayser and tell me that MPD and Code Enforcement are taking care of things.

A primary problem — Memphis has never had a strategy to defend its tax base. It has not understood the economics of reinvesting in our neighborhoods. We still invest to facilitate sprawl and flight,while our rhetoric says otherwise. And, for years, much of our funding has gone into Lipscomb’s vanity projects.

Rebuilding in our neighborhoods — done strategically to stimulate the for-profit market — is something we cannot afford not to invest in.

Frayser CDC