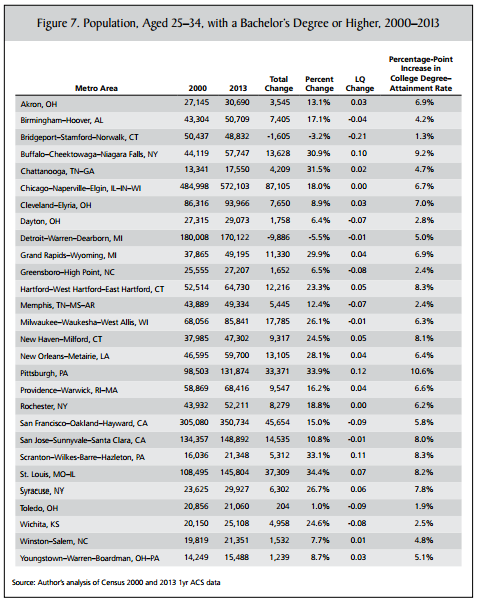

Memphis MSA gains 62,796 people between 2000-13 who have bachelor’s degrees or higher and 5,445 people with degrees between ages of 25-34. Respective percentage increases are 4.4% and 2.4% (which are among the lower growth rates), but at least the region is in the positive.

“It appears, the Rustbelt’s tide may well be turning. A fascinating study released last week by Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute (who many know as The Urbanophile), provides detailed data that shows that the Rustbelt has shifted from brain drain to brain gain.”

From CityLab:

Brain Gain in the Rustbelt

No region of the United States has been harder-hit economically in recent decades than the Rustbelt. A lot of my own recent thinking—and that of other urban theorists—has been shaped by the plight of this great region. My earliest research in the 1980s and 1990s tracked the transformation of its manufacturing base in the wake of sweeping deindustrialization and the annihilation of millions of once family-supporting jobs. My 2002 book, Rise of the Creative Class, grew out of my firsthand observation of Pittsburgh’s deindustrialization, its subsequent strategies for high-tech renewal, and the movement of both high-tech companies and talent from the region. I called it my “base case,” commenting that if Pittsburgh, with its great universities, neighborhoods, and other assets could not make it, what other older industrial cities could? And, in a 2009 essay for The Atlantic, I noted how the economic crisis had left Rustbelt cities like Detroit staggering.

But lately, it appears, the Rustbelt’s tide may well be turning. A fascinating study released last week by Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute (who many know as The Urbanophile), provides detailed data that shows that the Rustbelt has shifted from brain drain to brain gain. The region now boasts an increasing population of highly educated residents at rates above the national average, and even above some of the nation’s leading tech and knowledge hubs. Renn’s study zeros in on the gain or loss of college-educated residents across America’s so-called “shrinking” metro areas. He defines these shrinking metros as those among the nation’s 100 largest that experienced population or job loss between 2000 and 2013. Ultimately, he focuses on these trends in 28 metros, the vast majority of them in the Rustbelt (though note well that San Francisco and San Jose also made this list, as they both lost jobs over this period).

Rustbelt Brain Gain

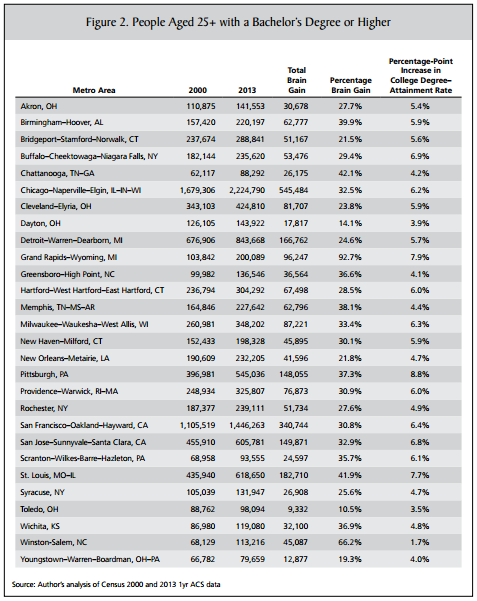

The table above charts the brain gain or drain for these 28 metros based on the change in the number of residents age 25 and above with a bachelor’s degree between 2000 and 2013. Grand Rapids saw the largest percent change in brain gain (with a 92.7 percent increase in college educated adults between 2000 and 2013), followed by Winston-Salem (66.2 percent); Chattanooga (42.1 percent); and St. Louis (41.9 percent). This compares to roughly 30 percent for San Francisco and 32.9 percent for San Jose.

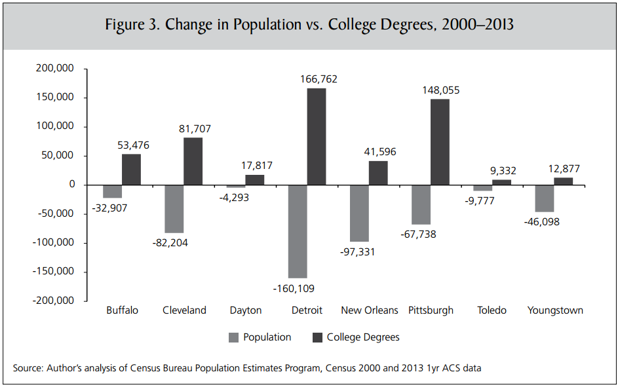

The next chart below provides additional perspective, comparing the change in total population to the change in population with a college degree for the eight metros that experienced population loss from 2000-2013 (seven Rustbelt metros and New Orleans, as a consequence of Hurricane Katrina). Of these, Detroit and Pittsburgh saw the largest increases in college educated residents, followed by Cleveland, Buffalo, and New Orleans. While Detroit’s overall population declined by more than 160,000, it gained nearly 167,000 residents with college degrees. And while Pittsburgh’s population declined by over 67,000, it gained 148,000 college grads.

Talent Migration

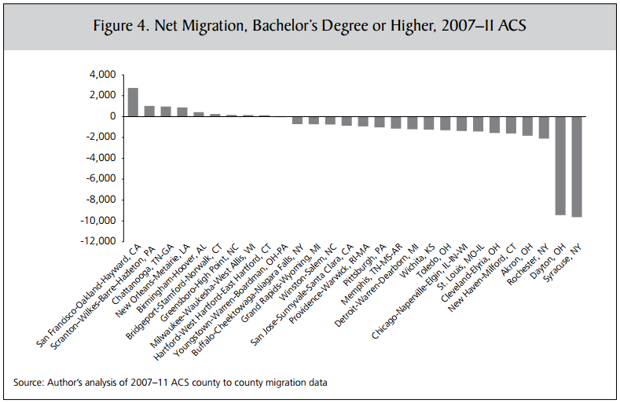

The picture is not entirely rosy, however, as the chart below, which tracks the net migration of college grads to and from these 28 metros between 2007 and 2011, shows. Only four of the 28 metros saw sizable gains. Eighteen saw a continued outmigration of college grads, with Syracuse, New York, and Dayton, Ohio, seeing by far the biggest loss. But it’s not just Rustbelt metros that are losing college-educated residents. As the chart points out, San Jose saw a similar outmigration, as did Chicago.

The outmigration of college grads is not just the province of shrinking metros. “In fact, more net residents with college degrees left New York than any other U.S. metro during 2000-2013,” Renn notes. “But no one frets that New York is hemorrhaging talent.” The reason of course is that New York and places like Boston, D.C., and San Francisco have a much greater concentration of highly educated people to start with. That said, this chart shows that the majority of these metros continue to suffer from a net outmigration of talented people.

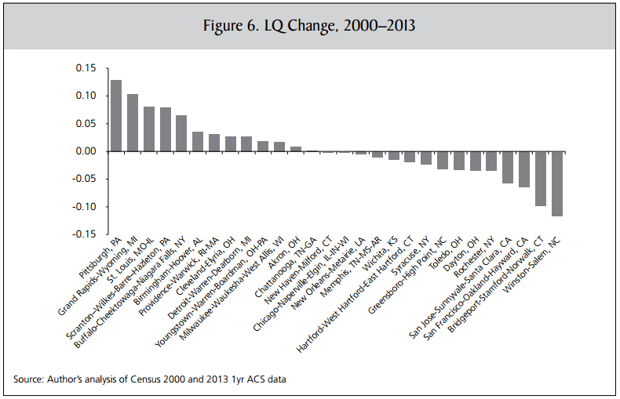

To get a more accurate sense of the ability of shrinking cities to attract talent, Renn turns to a location quotients, LQs for short, a frequently used metric in regional analysis. (An LQ of 1.0 means a metro is in line with the national average, greater than 1.0 means it is above the national average, and less than 1.0 means it trails the nation.) As the chart below shows, roughly half of the metros in this group, including Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Milwaukee, saw their LQ scores improve, meaning that they were more educated compared to the U.S. average in 2013 than in 2000. The other half, including San Francisco and San Jose, as well as Memphis, Toledo, and other Rustbelt metros, saw theirs decline. As Renn points out, “cities like Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo that are widely viewed as downtrodden…are actually catching up with or surpassing the rest of the U.S. in education attainment rates.”

While most people picture young, talented people moving to places like New York, L.A., the Bay Area or D.C., 26 of the 28 shrinking metros saw a net gain of young adults ages 25 to 34 with college degrees from 2000-2013, as shown on the table below.

Peaks and Valleys

This brain gain among Rustbelt metros is indeed, to quote Renn, “cause for celebration.” Over the past decade or so, some of the nation’s hardest-hit cities and metro areas have reversed their loss of talent, and now are gaining educated people, including educated young people, according to several metrics.

A good deal of this stems from basic demographics. When places like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit deindustrialized, they lost a good chunk of their younger, more skilled residents, who moved away to find work and opportunity, leaving older, less educated residents behind. But as those populations have aged and these cities have experienced “generational turnover,” that skills gap has begun to reverse. Younger Americans, after all, are much more likely to hold a college degree than their grandparents (32.9 percent for ages 25-34 compared to 24.1 percent for Americans over 65).

This process is amplified by the fact that many, if not most of the metros on Renn’s list are home to great colleges, universities, and medial centers, which help attract talented professionals and are also more likely to retain students as their economies and employment opportunities improve. And of course, these gains are also a product of starting from a relatively low base, compared to existing knowledge and tech hubs that had much greater concentrations of educated residents back in 2000.

Still, the brain gains seen by many Rustbelt metros are also a result of making talent a key part of their economic development strategies. It’s time to recognize that talent-based strategies work and can be a useful piece of the economic development toolkit. In fact, this may be where educational and medical institutions—so called “eds and meds”—play the biggest role. As Renn himself has previously pointed out (and I agree), eds and meds have not been particularly effective at spurring high-tech development. A more appropriate role seems to be in attracting and retaining talent.

Despite such admirable progress, Rustbelt metros continue to lag America’s leading knowledge hubs by a considerable margin. Alan Berube of the Brookings Institution points out that 7 of the top 10 metros that had the largest share of college grads in 1970 remained so in 2010, even as a number of older industrial metros like Pittsburgh and Dayton improved their positions. As of 2012, roughly 30 percent of adults in Pittsburgh were college grads, 28 percent in Detroit, and 25 percent in Dayton compared to 48 percent in D.C., 45 percent in San Jose, and 44 percent in San Francisco.

When all is said and done, these Rustbelt metros are among America’s largest and have considerable assets, from great knowledge institutions, accessible airports, and great parks to historic downtowns and neighborhoods filled with factories, warehouses, and other old buildings that new startups and talented people seem to prefer. Yet despite their gains, these metros remain far behind the nation’s leading knowledge hubs and superstar cities, not just in their share of highly educated talent, but even more so in their ability to generate innovation, startups, and high-tech industries, which remain highly concentrated in the Bay Area and the Boston-NY-Washington Corridor.

So what does the future hold for the hundreds of smaller metros that lack these sorts of assets? As Renn himself has noted, globalization creates vey real winners and losers among cities. “Meanwhile, back in the ‘spiky world,’” he wrote in 2012, “the peaks thrive while the valleys suffer. But it is the highest peaks that thrive most of all.”

The news of Rustbelt brain gain is indeed good, but it may not be time to celebrate just yet.

Somehow the article is not enlightening. As I sort through it, it is really hard to tell where Memphis is doing OK and where it is doing poorly. I guess there are two issues with the Memphis regional economy that I consider important. First, and most importantly, is the growth in African American college graduates. As an area with large black population, the growth and retention of black college graduates is extremely important. For years, as a professor at UM, I was excited by watching the number of black graduates grow each year. But are they working here or in Atlanta? Second, while college graduates earn far more than high school graduates, college salaries have plateaued in recent years. So we need a better sense of whether the number of college graduates in area is matched by the number of jobs requiring a college degree. I fear that Memphis may be failing here — we graduate people to take jobs that really don’t need a college graduate.

Great insight, David.

The bubble in Atlanta seems like it has burst, and people there are concerned that it’s not attracting the number of African American college grads that it attracted in the past. In the most recent four-year period, Atlanta was attracting high school graduates and people without HS degrees.

As you know, Atlanta built its economic juggernaut by attracting most of the African American talent in the Southeast, but these people seem to be spreading out these days.