We’ve known some of the core structural issues facing Memphis for some time, but few steps have been taken to address them in substantive ways.

Originally posted January 29, 2009:

Here’s the hypothesis:

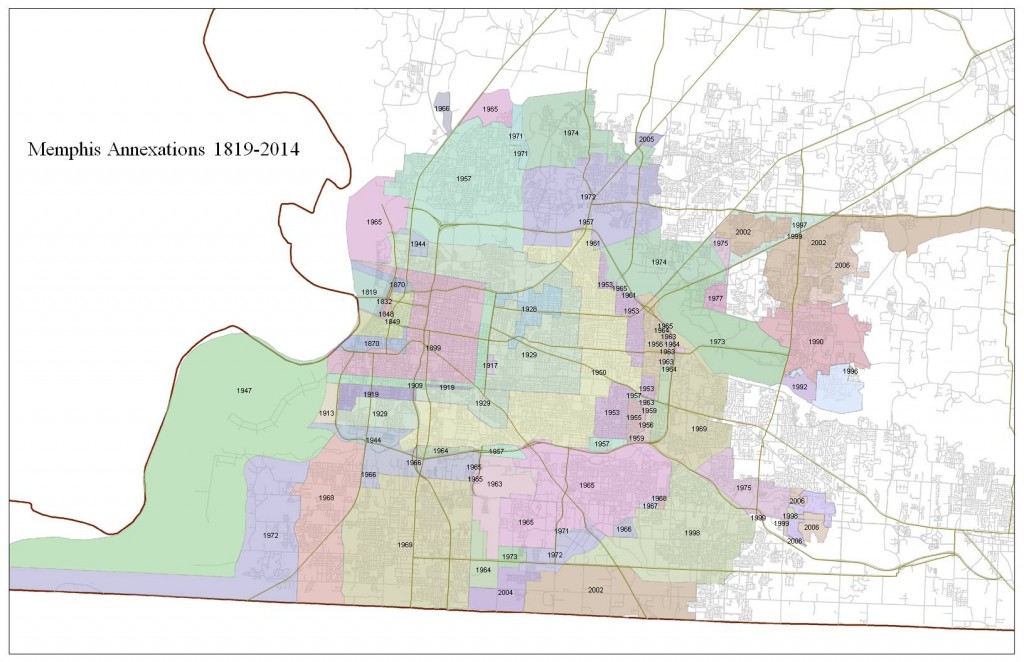

Tennessee’s liberal annexation law means that Memphis – unlike many similarly-sized cities across the U.S. – is not landlocked by small towns, and because of it, its population has been growing or relatively stable for several decades.

However, if we use the 1970 Memphis city limitsas the definition of the “core city,” Memphis is losing population, and annexation creates a false sense of security while older neighborhoods deteriorate and their problems intensify.

The Hard Facts

Here’s the fact that we mentioned in our last post: within the 1970 city limits of Memphis, population is 20% less now than then. In the meantime, Memphis has cut its density in half as it annexed about 150 more square miles of land.

The lure was new property taxes for a city – like every local government in Tennessee – strapped by the most regressive tax structure in the United States. In other words, the less you make in Memphis, the more you pay as a percentage of your income, and as the city hollowed out and middle income families moved out of the city limits, there seemed to be little alternative but to chase new revenues wherever they could be found.

But it’s time to step back and look at it all again. It’s time for a reality check. If the price for that new revenue is more responsibility over a larger area and no more to spend on core neighborhoods that are the heart of Memphis, the entire transaction may have been built on a false economy. Now, as the Memphis City Council has courageously forced a new look at the old way of doing things here, perhaps it’s also time to conduct a comprehensive return on investment analysis – one that tells us more than how much property tax is being produced in the new annexed area and the cost of the new public services. More to the point, the analysis needs to determine the cost to the neighborhoods left behind as the city searches for the green pastures of additional money for its coffers.

It’s A Simpler Place

This isn’t intended to criticize an annexation policy that was unfortunately about the only arrow in the city’s financial quiver. The truth is that we are lucky to have the current state law on annexation, because it does not produce a county more balkanized and where decisions are made even more difficult. For example, every time the St. Louis airport has to enter into new agreements about its facilities, it must deal with a dozen different cities. Louisville is surrounded in Jefferson County by about 90 governmental units (even after consolidation), and Cleveland, just in Cuyahoga County, is smothered by 36 cities.

In some ways, we perhaps were whip-sawed by the fact that our government structure is so much smaller than other cities. In those places, it’s often harder to give away taxes when it requires so much complicated cooperation between cities, villages and townships.

But back to the subject, Memphis is a shrinking city, so it’s no surprise that we’re showing many of the symptoms that perplex other cities. More to the point, we need to get into the serious discussions about the futures of shrinking cities and what they can learn from each other.

Changing Vocabulary

It won’t be easy. Elected officials and economic development officials prefer understandably to talk about population growth, but we need to remember that shrinking isn’t necessarily the same as sinking. Perhaps, just perhaps, when it comes to cities, size doesn’t matter or at least it doesn’t matter as much we have traditionally thought. Now, thinking about cities like our does require a new way of thinking, looking for assets that can be leveraged and competitive advantage to be maximized.

In Memphis, more than anything, it requires our city to change its way of conducting business. Now, it feels more like we’re playing not to lose, rather than we’re playing to change the game so we have a chance to win.

At CEOs for Cities, our colleague Carol Coletta’s research has already shown that “cities that measure success by population growth have an outdated view of what success is all about.” She pointed out that arguing that there is a correlation between population growth and economic growth and per capita income growth is wrong as much as it’s right. For example, Las Vegas topped the list in population growth while coming in 38th in income growth.

The Right Size

Pretending that it doesn’t exist is sort of like being in the ER but refusing to acknowledge that you are hemorrhaging. In cities, it results in massive public infrastructure that a smaller number of taxpayers have to pay for. As part of the shrinking city discussion here, we also need to consider how we right size the relationship between who needs and who pays for these kinds of expensive services.

The shrinking cities movement began in Germany following the fall of Communism and the historic shift in populations from East to West. As part of its research, it looked to Halle/Leipzig in Germany, Detroit, Ivanovo in Russia and Liverpool/Manchester in England.

The city that has embraced its shrinkage is Youngstown, Ohio, just as planner Gerald Nicely has turned around Tennessee Department of Transportation, is another planner, Mayor Jay Williams, who made Youngstown come face-to-face with its dire realities. He was elected after shaping a broad-based blueprint based on a simple fact: Youngstown would be smaller.

Straight Talk

He talked bluntly and embraced the philosophy that his city had to act radically and quickly. He’s not taken anything off the table, including de-annexations and digging up utilities and roads. It was a gutsy move for a mayor, but he refused to gloss over the problems and the reality of the future they would create if nothing was done.

Youngstown was always a “mill town,” and that’s why the shutdowns of the mills that began 30 years ago turned the city upside down – financially, civically and culturally. It took 30 years for the dose of reality that would lead to the election of Mayor Williams, and today, he and his city are now recognized for Youngstown 2010, which advocates strategies ranging from increasing density, removing streets from the traffic grid, tough changes in the delivery of public services, plans to remove large areas of abandoned houses and programs to lure people to areas where city services can make financial sense. That last one is particularly tough politically. If it were not so, residents of the Lower Ninth Ward is New Orleans would not be building new houses.

We’re not saying that the shrinking city movement has all the answers. We’re just saying that we need to start the discussion. We’ll be in good company, or should we say, we’ll be in company. More than 450 cities with populations more than 100,000 have lost 10% of their populations since 1950, including 59 in the U.S. For every two cities gaining population, three are losing population.

Talking The Talk

One conclusion that has received consensus already: traditional urban planning tools don’t work. That’s been proven by the slum and blight removal programs, followed by the urban renewal projects, followed by the economic development initiatives. Now, some cities are appealing to the young creatives who are not scared off by urban challenges but often find the funky environment and cheap digs that are so often lacking in boomtowns, and they are important.

However, they certainly won’t create solutions at the scale needed by cities like Detroit, where city housing is now going for $7,500 or for Memphis whose number of vacant properties has doubled since 2000 to about 14,000. But what it just might do is tap into the creativity and new thinking that creative workers and young talent offer for real solutions for Memphis. We have some now who need to be part – if not leading – this new discussion about the future.

In other words, this isn’t about creating a throwback to the past, but injecting new vibrancy and activity into nodes that together can stitch together the torn fabric of a shrinking city.

But first, we have to decide to begin. Too often, dealing with urban problems in Memphis is like the stages of grief. Just this once, maybe we can move past denial, anger, bargaining and depression, and unabashedly move to acceptance and develop the kinds of bold plans that can truly make a difference in the trajectory of our city.

Good post.

There is something to be said for annexation, which I guess means there is something to be said for a false sense of security since 1970. It is not hard to guess what Memphis would be like if Raleigh, Frayser, and WHITEhaven had not been annexed — and what might have happened to those places as Tipton County, Millington, DeSoto County, and Bartlett grew. Shelby County property taxes look like Delta’s seat-pricing, and change about as often. Segregation and resegregation are the root causes of so many of our problems here as they are elsewhere. Shrinking might make some sense, but why should one homeowner pay $7+ property tax rate while another a quarter mile away in, say, Southwind or Windyke, pays $4+ as was the case for the last ten years?

John Branston