To follow up this morning’s post about Riverside Drive, here’s an article by Kaid Benefield at Sustainable Cities Collective about the power of good street design to improve cities like Memphis:

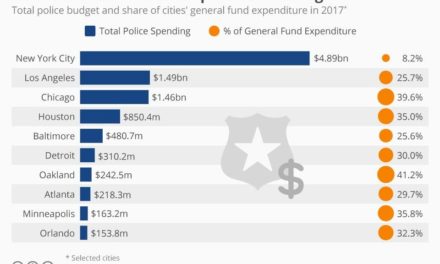

The study examined projects that had before-and-after data from transportation and economic development agencies, spread across 31 cities in 18 states.

In a blog post, Smart Growth America staffer Stefanie Seskin highlighted five particular findings from the report:

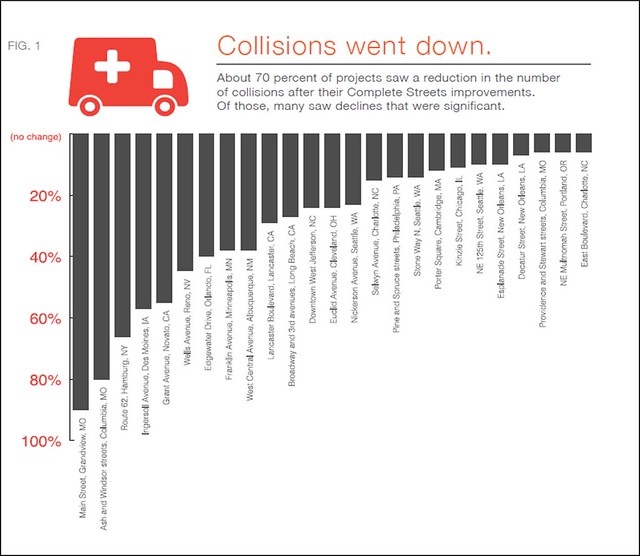

- Streets were usually safer: Automobile collisions declined in 70 percent of projects, and injuries declined in 56 percent of projects.

- This safety has financial value: Looking only within the sample, Complete Streets improvements collectively averted18.1 million in total collision costs in just one year.

- The projects encouraged multimodal travel: Complete Streets projects nearly always resulted in more biking, walking, and transit trips.

- Complete Streets projects are cheap: The average cost of a Complete Streets project was just2.1 million–far less than the9 million average cost of projects in state transportation improvement plans.

- They can be an important part of economic development: The findings suggest that Complete Streets projects were supportive of increased employment, net new businesses, higher property values, and new private investment.

(Full disclosure: I am a board member of Smart Growth America. I have had no connection with or advance notice of the study I am reporting today.)

For example, the report highlights Dubuque, Iowa, where the city reconsidered four main avenues in its historic Millwork District, replacing sidewalks, easing pedestrian street crossings, adding new street lights, painting “sharrows” (designed to alert other users that bicyclists are sharing the road space), and creating a multi-use trail. Within a year, bicycling use increased by 273 percent.

Since the project’s completion, the neighborhood has experienced more than $34 million in new private investment, with another $150 million in the pipeline. While it is impossible to determine an accurate fraction of that investment due specifically to the street changes, community leaders believe that the fact that the neighborhood’s streets work for everyone who uses them and visits the district is an integral part of its success.

It is a basic tenet of the Complete Streets movement that it does not offer a fixed prescription to apply in all situations but rather a menu of approaches that can be adapted as circumstances warrant.

From the beginning it has been more a political movement than a design strategy: the objective of the Coalition has been the incorporation of a core principle – that streets should serve different kinds of users – into state and municipal policies for roadway design and safety. Localities can then interpret and implement that principle with flexibility.

I last wrote about Complete Streets in 2013, when I noted the very good news that many streets today look and feel different – more thoughtfully designed, with more than just cars in mind – than they did, say, twenty years ago.

As I noted then, I live in a community (Washington, DC) where, depending on circumstances, I am at times a driver, a pedestrian, a cyclist, and a transit user. And, where these kinds of changes have been made, I feel safer and better accommodated as a pedestrian and cyclist – and, remarkably, not at all inconvenienced as a driver.

Indeed, my experience has been that automobile traffic pretty much moves as well (or as poorly) as it always has and, in some cases, it moves better because everyone’s spaces are better delineated.

The new study (titled Safer Streets, Stronger Economies) found that, in about half the projects, automobile volume increased or remained unchanged after the redesigns.

One of the most impressive examples in the report is in Orlando. I can’t improve on the authors’ description, so here it is:

“Edgewater Drive acts as the main street for College Park, a neighborhood four miles north of downtown Orlando, FL. When the street was scheduled to be resurfaced in 2001, the community saw an opportunity -to reinvent Edgewater Drive into a vibrant, pedestrian-friendly commercial district with cafés and shops.’

“The City of Orlando proposed a 4-to-3 lane conversion for 1.6 miles between Par Street and Lakeview Street, adding bicycle lanes, a center turn lane, and wider on-street parking. With resident input, the City of Orlando devised an extensive series of performance measures to monitor the project’s progress. These measures included travel times, traffic volumes for all modes, and safety-related crash and injury rates, and speeding data.”

“The newly improved street was clearly safer than before. Total collisions dropped 40 percent, from 146 to 87 annually. The crash rate was nearly cut in half, from 1 crash every2.5 days to 1 crash every 4.2 days. Injuries fell by 71 percent, from 41 per year to 12 peryear, and instead of 1 injury every 9 days, the reconfigured street saw 1 injury every 30days. These safety findings are particularly impressive considering that automobile trafficonly decreased 12 percent within a year following the redesign, while bicycle countssurged by 30 percent and pedestrian counts by 23 percent.”

“As a result, more people want to be on Edgewater Drive. The corridor has seen 77 net new businesses open and 560 new jobs created since 2008. Average daily automobiletraffic, which saw a slight dip following project completion, has returned to its original pre-projectlevel and on-street parking use has gone up 41 percent.

“The most dramatic results, however, were in long-term real-estate and business investment. Since the project was first proposed, the value of property adjacent to Edgewater Drive has risen 80 percent, and the value of property within half a mile of the road has risen 70 percent.“The street was resurfaced again in 2012. No one suggested it should go back to its original configuration.” (Emphasis in original.)

The financial savings of Complete Streets due to accident reduction are particularly significant: while the analysis found that the safer conditions created by the 37 projects in the study avoided a total of $18.1 million in collision and injury costs in a single year, those savings will continue to mount in subsequent years.

The financial impact of automobile collisions and injuries nationwide is in the billions of dollars annually. The report’s authors conclude that “targeting the country’s more dangerous roads and taken to any meaningful scale, a Complete Streets approach over time has the potential to avert hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in personal costs.”

With respect to economic effects other than savings due to accident avoidance, the authors concede that “before-and-after data in this area are scarce for all kinds of transportation investments and Complete Streets projects are no exception.” Of the 37 projects included in the survey, the Coalition was able to examine changes in employment in 11 places, and changes in business impacts, property values, and/or total private investment in 14 places.

The authors found found that employment levels rose after Complete Streets projects–in some cases, significantly. Communities reported increased net new businesses after Complete Streets improvements, suggesting that Complete Streets projects helped make the street more desirable for businesses.

In eight of the ten communities with available property value data, the values increased after the Complete Streets improvements. And eight communities reported that their Complete Streets projects were at least partly responsible for increased investment from the private sector. These data support the economic outcomes reported anecdotally by many communities.

The authors correctly concede that more and better data would be needed to conclusively connect Complete Streets with economic success. But the proposition that such measures can support economic activity does make intuitive sense: comfortable foot traffic, in particular, is good for business, and one of the basic objectives of Complete Streets is to make walking feel safer and more comfortable.

In the end, Safer Streets, Stronger Economies is less a scientific study than a compilation of available (and, to a great extent, differing) data from a limited range of case studies. To my mind, it is far from conclusive. But the direction in which it points is very encouraging for those of us who want healthier travel and living environments for everyone in America’s communities.