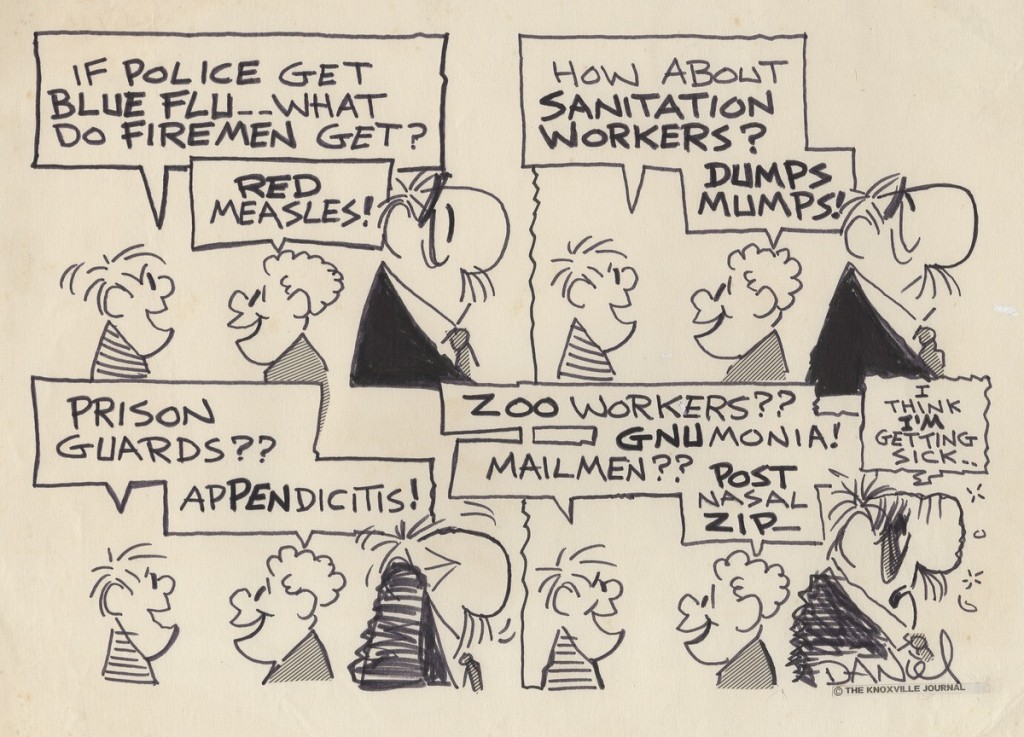

There is a developing theme on social media that demonstrates just how badly Memphis police officers have shot themselves in the foot with their sick-out.

It’s this oft-read comment: I haven’t noticed any change with more than 450 officers calling in sick, so maybe we didn’t need them in the first place.

It is impossible to base policy decisions on anecdotal comments, but interestingly, this one calls up the recommendations in City of Memphis efficiency studies which dealt with the number of commissioned officers.

More and More Hiring

Back in 2007, Deloitte recommended in its City of Memphis Efficiency Study that the complement for Memphis Police Department could be as low as 2,637 or as high as 2,833, depending on decisions about patrols. The study recommended that MPD reduce the number of PSTs, increase the number of civilians, and stop responding to minor non-injury traffic accidents.

In 2007, the full-time equivalent employees in MPD were 2,685 according to the City of Memphis CAFR (Comprehensive Annual Financial Report). Only six years later, the number had climbed to 3,032 employees, or about 200 more than recommended in the efficiency study as its “high side” number.

Looking at the 10 years between 2004 and 2013, the MPD workforce grew from 2,666 to 3,032. By way of comparison, Memphis Fire Department increased from 1,773 employees to 1,831, and by the end of the decade, three out of every four City of Memphis employees worked in police and fire divisions.

Meanwhile, the number of physical arrests by police in 2004 was 88,076 and decreased to 46,116 in 2013. Parking violations fell from 122,044 to 87,536 and traffic violations fell from 229,222 to 178,934.

More Officers With No Operating Benefit

By way of comparison, fire calls fell from 64,691 in 2004 to 24,522 in 2012 (MFD has 12 times more ambulance calls than fire calls). According to last year’s Multi-Year Strategic Fiscal Plan by PFM, the police department receives more than one million calls and about 50,000 of them are actual crimes. The report also said that many civilian functions, particularly administrative in nature, have become the responsibility of sworn officers.

“Rather than these sworn personnel being assigned to proactive policing, responding to calls, or other higher-priority jobs for sworn personnel, an increasing number of MPD’s sworn employees became – in essence – more expensive versions of civilians,” the strategic fiscal plan said. “The net result was an operational wash (no increased benefit of police presence or patrol) and a more expensive staff.”

In addition, the report emphasizes that hiring more police officers “is not the only method to reduce violent crime.” “Between 2006 and 2011, seven U.S. cities of 500,000 or more residents achieved violent rate reductions of greater than 25 percent – a quarter more than Memphis. No city with 500,000 or more residents had an increase in officers per 100,000 residents greater than Memphis, and three other cities of 500,000 or more resident achieved violent crime rate decreases with a reduction in officers per capita.

“Within Tennessee, Nashville achieved a 22.7% reduction in violent crime between 2006 and 2011 and slightly reduced its number of sworn officers per 100,000 residents. During this time, other cities decreased FTEs and sworn officers per 100,000 residents and achieved greater reductions in violent crime…Memphis remains an outlier in the size of its police department when compared to other cities with 500,000 or more residents that have achieved the greatest reductions in violent crime over five years.”

It’s More Than Lock ‘Em Up

The report said that the link between the number of police officers and crime rate reductions is “at best, elusive.” “Different studies have found different relationships and data suggest variation by city. As a result, other approaches related to crime prevention, prosecution, and punishment may have as much, if not more, of an impact on crime reduction and often come at a lower cost than sworn police officers,” the report said.

Some of these other alternative crime reduction programs include teen courts and family-based therapy for juvenile offenders, restorative justice for low-risk offenders, employment and job training for prior offenders, intensive supervision, and community-based drug treatment programs.

“Crime reduction requires a balance between investments in prevention and policing to achieve crime reduction based on research and cost-benefit analysis,” the report stated. “If the City chooses to continue its reliance on policing as its primary means of achieving crime reduction, it must find a way to pay for it – the current method is fiscally unsustainable…the City cannot afford the current level of police FTEs.”

The paradox of the current pension controversy and retirees’ benefit controversies is that they may be the result of a vicious fiscal circle in city government. Over a decade, more and more money was spent for public safety and more and more officers were hired. That in turn took away money to hire more officers that could have used to pay for pension and health costs.

Essentially, the success of the city’s public safety divisions (aided by the unions and enabled by the lack of courage by city officials to say no) in getting more money to hire more officers in large measure has led to the current crisis. In this way, today’s crisis is one of their own making.

Change But No Tax Increase

Meanwhile, numerous speakers before Memphis City Council have said that the public is opposed to the actions that have been taken. In December of last year, in connection with the Multi-Year Strategic Fiscal Year, a poll was taken (we’ve previously posted the survey results), and it was clear that the public was willing to change pensions and that they abhorred a tax rate increase to deal with the funding challenge.

Sixty-five percent said they supported changes to pension plans held by current city employees in order to contain future pension costs, and 22% opposed (the others weren’t sure). Asked if property taxes should be increased to pay pension obligations, 72% said no and 19% said yes.

Interestingly, when asked if they would support changes to the pension plan if changes were negotiated with unions, support went down to 58% with opposition at 25%.

It’s probably impossible at this point to convince union members that calling in sick has hurt their cause and that their online attacks and strong-arming behaviors on anyone who disagrees with them leave them with even fewer supporters, so we won’t even try to convince them that in large measure, it was climbing public safety budgets that limited City of Memphis’s options to pay for pensions and benefits in the first place.

Fabulous context. Thanks so much.

Excellent read.