During the Pre-K campaign, our friend and long-time Memphis blogger Steve Steffens (LeftWingCracker) often said that although Pre-K is important, in truth, interventions with our children should begin even earlier in their lives.

There is no question that he is right.

He commented on one of our posts about Pre-K: “Pre-K is a good start, but ONLY a start. We need intervention from birth, and no, I am not kidding. Pre-K is a good thing, but it’s only a part of the things that need to be done to truly change what is happening in Memphis.”

Our response: “No question at all, Steve. You are so, so right. By the age of three, a child’s mind grows to 80% of its adult size. It is a sponge. We were watching a TED talk last week in which the speaker said that babies’ brains are the largest computers in the world. At what level they operate is heavily dependent on those early years, and if we are serious about Memphis children, we have to be serious from the day they are born.”

Babies’ Brains

Here’s the captivating TED talk, “What do babies think?” by psychologist Alison Gopnik that we were referring to. “Babies and young children are like the R&D division of the human species,” she said. Her research explores the sophisticated intelligence-gathering and decision-making that babies are really doing when they play.

It’s a fascinating commentary on the power of the most sophisticated learning computers on the planet – our youngest children’s brains.

More Vocabulary, Better Outcomes

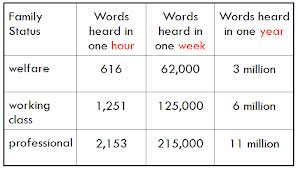

All of this has special meaning to Memphis, where 44% of our children live in poverty. Decades of research has shown that the children of lower-income, lower-educated parents typically enter school with poorer language skills than their peers from more privileged backgrounds. Previous research has concluded that five-year old children living in poverty score more than two years behind on standardized language development tests. By their third birthdays, children from more well-to-do families and whose parents are more educated have heard roughly 30 million more words than the children of less educated parents.

Stanford University researchers have now concluded that these differences begin to emerge by the time that a child is 18 months old. “By two years of age, these disparities are equivalent to a six-month gap between infants from rich and poor families in both language processing skills and vocabulary knowledge,” the primary researcher said. “What we’re seeing here is the beginning of a developmental cascade, a growing disparity between kids that has enormous implications for their later educational success and career opportunities.”

The link between a child’s early vocabulary and later success in reading comprehension is well-documented. This isn’t about flash cards and memorization for young children. Rather, it’s about the important impact of natural conversations with children, asking questions while reading books, and helping children identify words during playtime. Parents living in concentrated poverty who speak to their children more frequently can enhance vocabulary, because those children who hear and understand more words had larger vocabularies by two years old.

Memphis children from impoverished backgrounds deserve better. They deserve programs – and the civic commitment – that level the playing field at the earliest possible age, because the language gap is real and difficult to reverse.

Memphis Talks

We’re not saying that Pre-K isn’t crucial. It is, but in a city that can’t get its act together enough to pass funding for Pre-K, we worry about our ability to organize the programs to give every young child a fair start in life.

Of course, this isn’t a problem only for Memphis. The National Governors Association has called on states to ensure that all children can read proficiently by third grade and urged lawmakers to increase access to high quality child care and Pre-K classes and to invest in programs for children from birth to five years old.

In a state where our Tea Party Legislature seems more intent on punishing the poor than helping them, the likelihood of this wise approach being taken is essentially zero. In other words, it is incumbent on Memphis and Shelby County to take control of our own destinies, and Providence is a place with lessons for us.

As Mayor Angel Taveras of Providence, Rhode Island, said: “We need to really start in the cradle.” In his city, two-thirds of kindergartners show up on their first day already behind national literary benchmarks. Taveras will soon launch, “Providence Talks,” a program to take on the “word gap.”

Tune In But Not Drop Out

Providence will distribute small recording devices that tuck into a child’s clothes and automatically record and calculate the number of words spoken and the number of times a parent and child quickly ask and answer each other’s questions.

The program was inspired in part by the “30 Million Words” program in Chicago. That program is built on special kinds of parent-child interactions. It’s incumbent on parents to “tune in” to what the child is looking at, talking about, and ask questions that create a “serve and return” conversation between parent and child.

Plans for the Chicago program are to expand the program into child care centers and for it to be discussed. The program “is more than just talk,” its website says. “We’ve pulled from multiple disciplines to build a comprehensive curriculum that targets both the cognitive and behavioral development of a child.”

Good Place to Start

The program’s philosophy is summed up this way:

* Parents are children’s first and most important teachers.

* Enriching a child’s early language environment occurs through promoting parent-child interactions that have been linked to positive child outcomes.

* Enriching a child’s early language environment does not require changing cultural practices and values or idiomatic speech.

* Parents are Three Million Words’ most important collaborators. They have been part of the iterative process from the very beginning, creating, refining, and growing our curriculum into what it is today and what it will be tomorrow.

The demographics in Memphis and Providence are similar, and if that city can tackle the language gap, there’s no real reason why we can’t do the same. Everyone talks about the achievement gap, but we need to begin at the beginning – by addressing the language gap.