Local Memphis architect and planner Andy Kitsinger is now writing a regular column for the highly respected Planning Commissioners’ Journal. He is a principal consultant at The Development Studio, a firm focused on helping clients build stronger communities. He writes about Downtown and Main Street Issues.

His first piece ran this week:

Downtowns in many American communities have experienced more than fifty years of neglect, abuse, and abandonment. There are a number of factors that have contributed to this indifference toward our central cities. Several decades of bad public policy, private market forces, as well as individual prejudices have all worked counter to the health of central cities.

Fortunately over the last two decades this trend has slowly begun to shift. Today, cities of all sizes have implemented plans to revitalize, re-grow, and reinvent their downtowns.

Why are downtowns important and why the need for all of these revitalization strategies? Because downtowns are the heart of a city and region — and having a healthy heart is essential to having a strong city and region.

Noted urban economist Edward Glaeser recently described cities as mankind’s greatest invention. Glaeser noted that while urban cores have a reputation of being “dirty, poor, unhealthy, crime-ridden, expensive and environmentally unfriendly,” they are actually the “healthiest, greenest, and richest (in cultural and economic terms) places to live.” 1 He makes a very forceful case for the city’s importance and provides economic proof that central cities are our best hope for the future.

In my hometown of Memphis, Tennessee, like many cities in United States, downtown’s decline began in the 1960s and continued for several decades. As in many other places, government policies and incentives fueled outward growth that left urban centers a shell of what they once were. This outward growth, now commonly referred to as “sprawl,” led to the erosion of city centers and massive income-based segregation. Other side effects from outward migration left the less mobile urban population with fewer job opportunities and access to basic services, as well as leaving children and the elderly lacking independence.

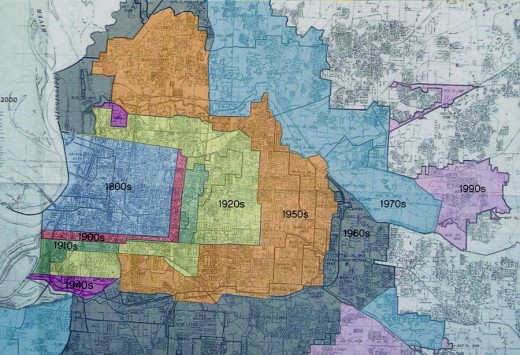

The City of Memphis’ annexation map reflects the outward migration and geographic expansion of the City. The geographic size of Memphis expanded from 50.9 square miles in the 1940’s to 340.5 square miles today. During that same time period, however, population density dropped from 7,800 to 1,900 people per square mile.

Although I use Memphis as one example, this pattern of low-density sprawl development continues to be prevalent throughout America and in many cities around the world.

To read more, click here.