We interrupt our blog posts – about the failure of our economic development and about the need for a comprehensive plan – to post some comments from two people who are precisely the target demographic that we need to give reasons to stay in Memphis.

Since we listed the negative economic indicators Monday that trouble us most and call into question our economic future, we posted a map yesterday that showed a blank spot where Memphis is supposed to be. It’s a map of high-tech start-ups, and Memphis was missing in action.

It’s yet another wake-up call for a community is adrift, unfocused, and non-strategic when it comes to economic development.

It’s not to say that there aren’t a lot of good things being done, but because we don’t have priorities, we are going in dozens of different directions. As a result, resources and energy are frayed and wasted, and opportunities to leverage them are often lost.

Get Serious

We have plans upon plans, but they are for initiatives, programs, and projects. There is not an over-arching economic development plan that is future-oriented, aspirational, ambitious, courageous, and balanced, that sets transformational priorities, and that can change the trajectory of Memphis and Shelby County.

Rather, we tend to do more of what we’ve been doing – think logistics. We are an internationally important logistics hub and we clearly should own that space, but we have to do more than identify logistics as the priority time after time. Surely, we can do more, and we have to if we want to keep and attract young college-educated professionals, inspire entrepreneurs, nurture startups, and compete on a global platform

As for us, we think we should quit talking about our logistics strengths until we are willing to correct the dismal condition of Lamar Avenue south of I-240, where so many of our logistics assets are located, and until we do something to make sure that the $1.3 million aerotropolis plan that is under way is not merely another missed opportunity.

A Memphis businessman asks: “Are we becoming a purely blue collar jobs capital?” Here are his comments:

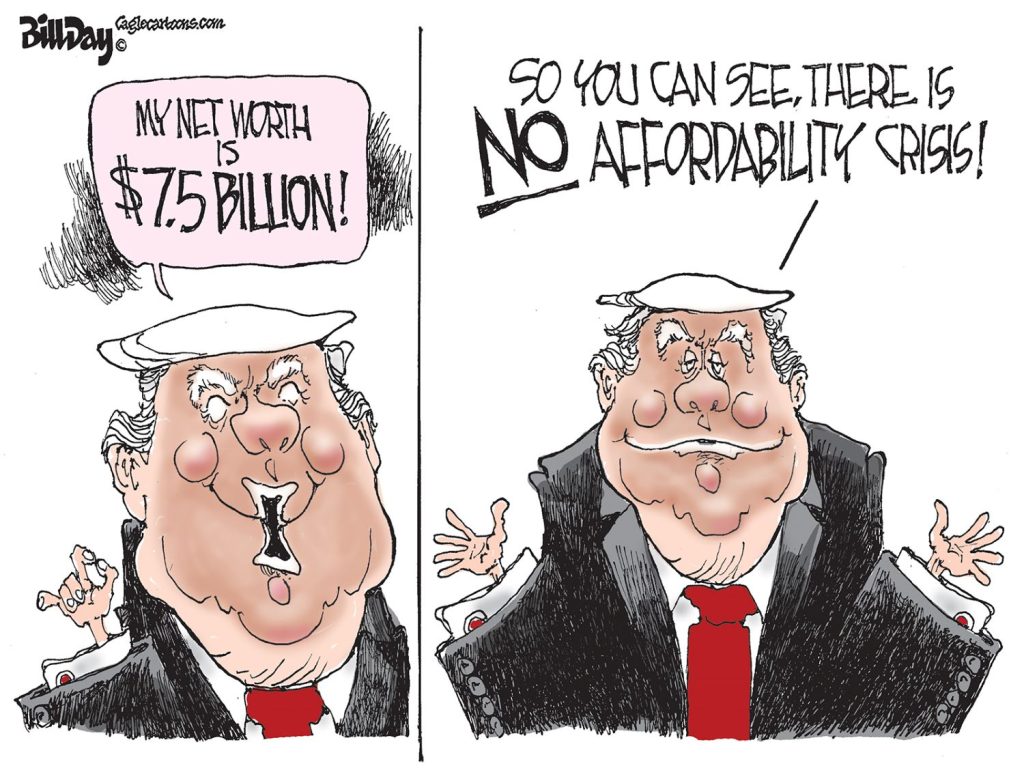

“Our white collar/professional job growth is virtually non-existent and too many of our job creation efforts seem myopically focused on “new economy” manufacturing, etc., not that those jobs are not needed here, but when downtown office, airport office, and Midtown office space activity is utterly abysmal (the only thriving office space sub market is East Memphis), it should tell you that we are headed in a singular direction of becoming a blue collar town (not for professionals).

“Are we oblivious to the fact that we have lost professional jobs in Pinnacle, Morgan Keegan, FedEx (those are the well-known ones) and before that, Harrah’s and Hilton Hotels Corp., and we continue to invest overwhelmingly in non-professional jobs. Simultaneously, we talk about talent and host events for young professionals saying come back/stay here, but we don’t pursue cultivating entrepreneurs to create local jobs for them nor have we prioritized incentives to lure the type of jobs here that the professional talent gravitates toward.

“I fear that by adopting and vocalizing the blue collar, grit-n-grind, ‘we are gritty and proud’ mantras, we only reinforce the thought process that we are doing the best we can with trading $75-$100,0000/year jobs for $35-$50,000/year jobs. It’s like our ever increasing poverty, education challenges, crime, racial tension, teen mother births, economic inequality, lack of population or economic growth, proximity to other poor counties, political turmoil, urban versus suburban standoffs are all emblematic of our true grit and scrappiness and we wear it like it’s a badge of honor.

“What happened to the city that birthed Holiday Inns, Universal Life Insurance, NBC Bank, First TN, Leader Federal, FedEx, Union Planters, Morgan Keegan, etc.? What major employers have we birthed lately (past 30 years since FedEx)? Are we structured/poised to birth any new ones or will we be solely reliant on the cheap labor/high subsidy job creation model to attract more Electrolux, Mitsubishi, KTG jobs that end up hiring a majority of their workforce from outside of Memphis from surrounding areas? I know there are professionals within these companies and that these companies will do business with local professional service firms, but that is a byproduct and not driven by priority.

“When Nashville’s #1 talent draw pool is Memphis, we have an immense problem.

“We should all be worried. It seems like the mayor should have a jobs czar who pushes the economic development job creation vision that he has for the community and that gives EDGE, Chamber, Brookings, Chairman’s Circle, Memphis Tomorrow, Mid-South Minority Business Council, etc., a specific piece to carry and deliver on, thus creating some degree of alignment with an overall vision and direction versus all of this free-styling, Lone Range initiatives that take up time, attention, money, and end up with unclear, unmeasured, mediocre results at best. Right now, it seems as though it is the flavor of the month rather them responding and aligning with his vision and direction. That’s what scares me most: the competing agendas that end up nowhere.”

In response to the same post, another astute reader – who’s a local professional – wrote:

“…but how many times have we been here or maybe the more accurate question is: how LONG have we been at this exact spot? Fumbling around with the same ideas and goals that we all agree with while those with the resources and positions to implement these strategies pay lip service to the concept by simply acknowledging the need, or worse yet, commissioning a 6-month study which places those exact words on high quality paper with generic images of young, smiling parents, professionals and children as they enjoy some nondescript activities? The final reports seem destined to gather dust on someone’s coffee table or to become gradually buried under other promotional and marketing material churned out by the Chamber.

“The region is akin to a stereotypical victim trapped and sinking in quicksand. ‘We’ are quick to grasp at the false and distracting escape offered by municipal school districts, random economic development projects such as oven manufacturers, unproven ‘green’ car assembly plants, providing tax breaks to jobs that are already in place, and airport gates. The more we struggle, the deeper we sink while quick observation, evaluation, and focused effort would likely lead to our salvation.

“The vine is there (damn it!), but it is going to require exerting some real physical force over a longer period of time than we prefer, and we may lose a shoe, a watch, and our shirt in the process. How do we snap ‘leaders’ out of the survival mode in which they seem to be entrenched when the fruit yielded by pursuing such goals will require a timeframe that spans multiple election cycles and thus the tough decisions that must be made stand a decent chance of costing them their political careers? How do you quickly reform a system that is built upon a foundation defined by a lack of change (or painstakingly slow evolution), is increasingly notorious for its devotion to self-preservation and is populated, and led by a large group of very loud individuals who are always prepared to defend the status quo?”

In response to the post about high-tech startups, the same reader said:

“When reading the title of the post, I thought it might be in reference to a finding that placed this area in the middle of the pack regarding our number of high-tech startups (or at least no more than two-thirds of the way down the list). Little did I know that Memphis would literally not appear at all. This provides more hard evidence showing that the Memphis Metropolitan Area has not even managed to simply tread water over the past two decades, but has lost ground when compared to both peer cities and to historic local performance measures.

“Consider this: Memphis and Buffalo may be the only metropolitan areas among the nation’s 50 largest MSAs to not show up on this map. Based on the report, Memphis has the dubious distinction of claiming the lowest startup density of any of the 52 metropolitan areas with a population greater than or equal to 1 million residents. The report also notes that the high-tech and ICT startup density in Memphis has actually decreased since 1990 (when Memphis did show up on the map). In fact, in 1990, Memphis was one of only handful of Southern metropolitan areas with a ICT startup density above the residual 0.0 – 0.5 and was comparable to places like Charlotte, San Antonio, and Indianapolis. Our startup density since 1990 has decreased by roughly 50%. – from 0.6 to 0.3 in both categories.”

As long as we continue to elect Mark Lutrell, AC Wharton or their clones to political leadership locally, or the group of clowns on the County Commission or Mark Norris, Jim Kyle, John Deberry and Brian Kelsey to the state legislature, there is no reason to expect anything other than more of the same.There is not one vision for Memphis’s growth among all of them.

I found this “blast from the past” while going through some old files. Neal Peirce is a nationally renowned writer about urban affairs.

Jobs Conference Memphis Has Turned Its Economy Around

April 11, 1987|By Neal Peirce

Publication ?

MEMPHIS — The 1980 Census found this old riverside port the poorest big city in America. Memphis suffered a deep guilt complex in the years following the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel in 1968. A prominent local banker acknowledges the city was close to an economic “death spiral” in the 1970s.

Yet Memphis has staged a stunning comeback in the ’80s. Federal Express, Holiday Inns and local enterprises are booming. Distribution firms added 5,000 jobs in 1985 alone. Tourism has moved from an afterthought in the city’s economic life to a $800-million-a-year business. Per-capita income is surging forward. The airport has become a major hub. Major corporate catches include International Paper, bringing 450 executives and a $30 million payroll from Manhattan.

Did all this happen accidentally, by the economists’ “invisible hand” of Adam Smith?

No way. Memphis hit the comeback trail when – and only when – it moved to heal its racial divisions, when business moved to strategic economic planning with strong citizen participation, and when a strong business-government partnership was formed.

Memphis may be the decade’s most vivid proof that our cities can be just as great – or mediocre – as their citizens and leaders make them.

The critical event here was the Memphis Jobs Conference, conceived and initiated in 1979 by Republican Gov. Lamar Alexander. Attending one of the conference’s concluding sessions in 1981, I was astounded to see one of the most “salt and pepper” – totally integrated – meetings I’ve witnessed anywhere in America.

“The Jobs Conference,” says Shelby County Mayor William Morris, “gave Memphis an understanding of itself – a sense of unity and purpose and direction for the first time. We got up off the mourners’ bench, developed a sense of self-esteem. It was the most important thing that has happened to Memphis in my lifetime.”

No one pretends, of course, that a community-wide forum for business planning and action could, or did, erase the deep economic gulf between Memphis’ blacks and whites. Memphis’ slums have not disappeared. Black-owned businesses lack much of a foothold outside ghetto areas and are unlikely to pick up more than the scraps from the region’s new economic advances.

David Cooley, back as president of Memphis’ Chamber of Commerce for the second time in his career. “I’m not dealing with a single person in the business leadership-structure I found here in the late ’60s and early ’70s,” he told me.

Then came Cooley’s clincher, underscoring not just new faces but radically shifted attitudes: “In addition to economic development, my board has given me four priorities this year: minority business development, expansion of low- and middle-income housing, education and training and, finally, consolidation of government.”

Consolidation of government – city and surrounding county? In most American metropolitan areas, it’s a pipedream. But not in Memphis. Morris vows to make it reality by the end of the ’80s.

FH-

Nice find. It makes this reader question so what happened. There was momentum generated locally in the 1980s. The local economy did begin to emerge from several major setbacks and new corporations were founded or relocated to Memphis. However, it seems that much of that momentum was lost by the turn of the 21st century. Back to what happened. Was the failure to capitalize on the nascent local economic recovery due to the same leadership that emerged from the job’s conference becoming lethargic with a tendency to rest on their laurels? Was it due to a handoff between generational leaders with the new class lacking the skill, training and understanding to drive the vision forward? Was it due to the political quagmire that developed with a representative body that now largely pursues a narrow, short term vision with a focus on that individual political careers? Did local economic growth simply pale in comparison to such an extent with the explosive growth which occurred in cities such as Atlanta, Dallas and Charlotte that Memphis failed to retain the first generation of tech savvy entrepreneurs at the dawn of globalization- a blow which continues to compound annually with the result being economic stagnation.

“I’m not dealing with a single person in the business leadership-structure I found here in the late ’60s and early ’70s,”

In 2013 Memphis is a city where the old maxim “it’s not what you know but who you know” makes us an insular, inward looking city.

Self-preservation masquerading as civic involvement drives away young new “thought leaders”.

Until a political movement is born to demand a more forward thinking local government nothing will change.

The following is excerpted from a Smart City Memphis post on August 25, 2011:

“Jobs Conference Lesson

We think back to the 1981 Memphis Jobs Conference, regularly hailed as one of Memphis’ finest hours, as disparate and diverse groups of Memphians came together to listen to the smartest thinkers on economic growth and to join hands behind new initiatives designed as game changers. Speakers before the SRO audience in the ballroom at The Peabody included nationally known people like Bob McNulty, president of Partners for Livable Communities, James Rouse, pioneering real estate developer, and others.

Speaker after speaker agreed on one thing: Cities have to take risks to succeed. Playing it safe would mean that Memphis could not compete with its competitors, and from this discussion came an emphasis on logistics, tourism, stronger economic development programs, Beale Street, Convention Center Hotel, Agricenter, and other strategies.

The message about risks is even more relevant today than it was then. Now, more and more of the incentives and programs for economic growth are being shoved down to cities and their governments to provide. It means that city governments have to be as sophisticated as the economy they hope to succeed in. It means that they have to find new ways to leverage dollars with the private sector or to make investments that spark new economic activity.

It is a trend playing out in cities across the U.S. and because the recession was international in its impact, it’s also playing out in Canada where cities are embarking on much larger, much bolder projects to keep their cities competitive. There are plenty of cities that decided to rest on their laurels and have faded from economic importance, some who decided to look backward at its glorious past while ideas and power flowed somewhere else.”

Urbanut, the last sentence about resting on laurels may apply to Memphis. Now we’ve got a lot of initiatives like business incubators, Brookings Institute’s Economic Development Plan, Fast Forward and its silos, MPO Transportation Plan, HOPE VI public housing redevelopment, et al, but as this blog site’s author keeps saying, we do not have a unifying, comprehensive development plan that everyone is behind.

The 1981 Jobs Conference’s most visible outcome was the priority spending of Governor Alexander’s $20 million on Beale Street, Agricenter, and the Convention Center Hotel; and logistics became the central focus of Memphis’ efforts to grow. What we haven’t done since is to reconvene a Jobs Conference with money on the table and find other sectors of the economy to exploit now that we have found a groove in tourism and logistics. Agricenter and biological technology may yet be a source of economic strength, but we haven’t seen an impact yet even though our region’s economy is based on agriculture.