From Atlantic Cities:

It’s ridiculously easy to think about the benefits of historic preservation in immensely walkable Providence, Rhode Island. I’m not sure I’ve seen a better collection of downtown historic architecture this side of New Orleans. Elsewhere there are fine smaller historic downtowns, of course, such as in Annapolis, and wonderful urban historic districts (frequently close to downtowns) such as Old Salem in North Carolina and Over-the-Rhine in Cincinnati. But in Providence, it’s the downtown itself that practically oozes with dignified charm.

I have a feeling that, as was the case with many fine older buildings in my hometown, Providence’s splendid architectural legacy remains intact because, when people were tearing down historic properties a few decades ago and putting up newer but mediocre buildings in their places, Providence’s economy simply couldn’t support the new stuff. So the splendid older buildings remain today, available to be given new life by creative-class businesses.

Providence may be a particularly fine example, but it is hardly the only city with underutilized historic assets that could become a cornerstone of future economic development. Information has largely replaced manufacturing as America’s economic engine, and young, talented workers today are seeking walkable districts with character in which to work and live. (Just ask suburban Dublin, Ohio about that.) From Pasadena to Portland, from Paducah to Providence, saving and sprucing up these assets is the way to go.

Scott Wolf is the executive director of Grow Smart Rhode Island, an organization that advocates asset-based economic development and smart land use.  Scott, who is my colleague on the board of Smart Growth America, argues persuasively that his state should capitalize on its historic architecture by encouraging older buildings’ rehabilitation and use:

Scott, who is my colleague on the board of Smart Growth America, argues persuasively that his state should capitalize on its historic architecture by encouraging older buildings’ rehabilitation and use:

Let’s restore our state historic-property tax credit to once again take advantage of our vast collection of historic buildings and neighborhoods, which we know are settings with great appeal for knowledge-economy companies and workers. It’s far from a coincidence that United Natural Foods, the largest distributor of organic food in America, relocated several years ago from Connecticut to the rehabbed ALCO site, in Providence, that Atrion Networking expanded into Hope Artiste Village, in Pawtucket, after that historic-tax-credit project opened for business, or that Moran Shipping, a technologically sophisticated, homegrown corporation with international reach, decided to forgo a move to Houston and instead relocate to a rehabbed building across from the State House.

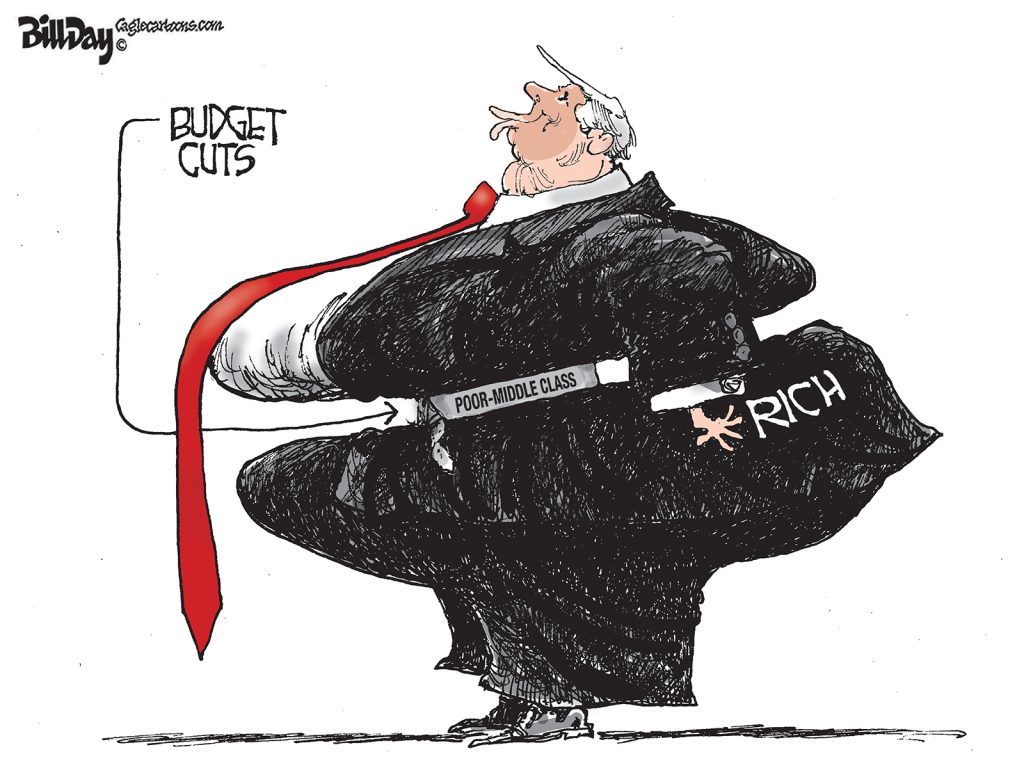

The federal government has a limited tax credit program for investment in income-producing historic properties: in particular, owners of buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places may be eligible for a 20 percent federal income tax credit that can be applied against the cost of their rehabilitation for reuse; in effect, 20 percent of the rehab costs will be borne by the federal government for most taxpayers. This reflects the public benefits of saving infrastructure and property.

But the federal incentive can be either undermined or strengthened by state law, depending upon whether there is a corresponding benefit available against state income taxes and, if so, how it is structured.

In many states, tax credits are indeed available to reduce the real cost of rehabbing historic buildings. According to an analysis by Harry K. Schwartz for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, most programs include variations on the following:

- Criteria establishing what buildings qualify for the credit;

- Standards to ensure that the rehabilitation preserves the historic and architectural character of the building;

- A method for calculating the value of the credit awarded, reflected as a percentage of the amount expended on that portion of the rehabilitation work that is approved as a certified rehabilitation;

- A minimum amount, or threshold, required to be invested in the rehabilitation; and

- A mechanism for administering the program, generally involving the state historic preservation office and, in some cases, the state department of revenue or the state department of economic development.

According to Grow Smart Rhode Island, that state’s Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission has found that, since 2002, Rhode Island’s Historic Tax Credit Program stimulated $1.2 billion of private investment in the rehabilitation of 208 historic buildings (mainly in urban and town centers) in 15 different communities. The Commission estimates that these projects created 22,000 construction jobs and 6,000 permanent jobs, and paid $806 million in wages, during that period. But the law was allowed to sunset, with its resurrection scheduled for debate in this session of the legislature.

I was honored to participate last week in Providence in an Earth Day program on how cities can celebrate diversity and culture while weaving together the interrelated needs of art, education, health and housing. The session, sponsored by the University of Rhode Island, was ably moderated by Marc Levitt, host and co-executive producer of the WGBH radio program Action Speaks.

In my portion of the program, I presented Mark Holland’s :Eight Pillars of a Healing City,” one of which is green buildings. (In a restatement of the principles by the Healing Cities Institute, this one became “restorative architecture.”) I emphasized that green buildings didn’t have to be new and that, in fact, older properties may have intrinsic green properties such as embodied energy and resources (that do not have to be spent anew as with a new building) and “original green” characteristics such as climate-specific design built before what Steve Mouzon calls “The Thermostat Age.” Older buildings also serve a less measurable, but no less important, function in constituting a shared cultural legacy. Simply put, they remind us where we – and our places – came from.

Providence is sometimes thought of as a declining city, but to me it seemed more like a promising one – poised for rebirth, fueled by the country’s emerging economy and demographics. Its chances – like those of other, similarly situated communities – will be enhanced if it recognizes the impressive assets that it has; builds upon those assets by courting the right kinds of businesses and residents that appreciate character and walkability; and preserves those assets for the future, starting with re-enacting the state’s historic property tax credit.