No public service attracts more magic answers, more instant experts, and more doctrinaire debate than urban public education.

Sadly, much of the discussion about public education is always anchored in two ideas: 1) public schools are bad, and 2) any program that takes students out of them is good. As a result, there are more superficial conversations about schools than any other public service, and rarely do the media call for the research that justifies the latest big idea that’s purported to solve all of the problems of public schools.

We’re not saying that we shouldn’t experiment with innovations in education or saying that many of the advocates for specific changes aren’t sincere or that they don’t care about the future of students and schools. However, many times these people, who are willing to have serious, thoughtful discussions, are overwhelmed by those with politically-driven agendas.

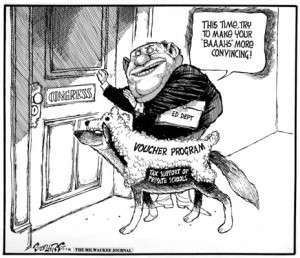

The latest example of this is vouchers, which are being pushed to implementation as a result of action by state politicians inspired by their right-wing agenda despite research that questions vouchers’ effectiveness. As a result, in the face of one of the most massive changes to take place in the history of Tennessee schools, there hasn’t been the discussion – engaging educators and academicians – that is needed so that educational policies are based on the facts and proven results. Rather, it’s been driven by the anti-urban school politicians who have now adopted new, palatable rhetoric about helping poor children get better education.

Consider the Source

Their sincerity requires, in the words of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a willing suspension of disbelief and it’s awfully hard to do it in this case because of the political dogma that propels it. After all, while the politicians pushing vouchers talk passionately about doing something to help poor students, they are simultaneously doing whatever they can to cut programs for the same families.

As a result, it’s hard to take them at their word (particularly since one of them once compared city schools to slavery) and even Stevie Wonder could see that their real purpose is to take aim on teachers’ unions (which to them, it is the scapegoat for all that they don’t like in public schools) and it is difficult not to be suspicious that the program providing vouchers for the poor is intended as a gateway to subsidies for the politicians more well-to-do constituents.

The Commercial Appeal opines that school districts must embrace school reform to succeed, but it begs the seminal question: what strategies should that school reform agenda contain? Rather than rush headlong with vouchers, why doesn’t state government take the time to test its talking points with a pilot program to test the theories that they claim will increase classroom results

What has always been remarkable about the new Tea Party majority in Nashville is how their actions so rarely reflect their allegedly ironclad principles. After years of extolling the evils of intrusive big government, state legislators are charging into every part of Tennesseans’ lives, but their school policies are particularly egregious.

Hard to be Trusting

They have already proven that they see public schools as vehicles to inculcate students with their doctrines, including mandates for teachers to teach religious beliefs rather than science, abstinence-only sex education that prohibits the discussion of almost anything related to sexual relations, and to ban the word, gay, from Tennessee classrooms. It’s hard to imagine that this group’s interest in vouchers is truly motivated only by their passion for the power of education.

It gives rise to suspicions that the vouchers, more than anything, are a way for state government to support religiously oriented private schools.

When it came time for a decision to be made about vouchers, it was made by state politicians rather than as a result of statewide discussions to determine if vouchers do in fact accomplish what the right wing rhetoric suggests. Instead, driven by political power rather than educational policy, they quote hyper-conservative research that sets out to prove a preconceived political position.

The research by nonpartisan, nonpolitical research institutes hardly suggest a clear victory for vouchers. According to the independent Center on Education Policy, a review of the past decade of research on school vouchers has found “no clear advantage in academic achievement,” and mixed outcomes overall, for students who attend private schools using vouchers.

Research Results

The report reviews and summarizes major studies on school vouchers from the past decade, and also summarizes current publicly funded school founder programs. According to the report, the scope of voucher programs and proposals has broadened over the past decade beyond serving just low-income students in low-performing schools to serving middle-income or suburban families. We suspect this is Chapter 2 in the Tennessee voucher plan.

In general, the report finds, several prominent voucher studies released since 2000, examining voucher programs in Cleveland, Milwaukee and Washington, D.C., have concluded that achievement gains for students receiving publicly funded vouchers are similar to those for comparable public school students.

“We have a great body of research about the effects of vouchers that policymakers should draw on to inform current debates,” study co-author Alexandra Usher said in a statement. “Before state legislators and Congress move quickly to enact new voucher programs, they should consider the evidence from programs already in place for several years to ensure they understand the impacts their policies would have.”

The report notes that many recent voucher studies have been carried out or sponsored by pro-voucher organizations, and recommends steps to ensure that studies are designed, conducted and reported in an objective manner. “We were surprised to find so many studies done by pro-voucher groups,” study co-author Nancy Kober said. “While this doesn’t mean researchers with definite positions on vouchers can’t be objective, it speaks to the need for outside scrutiny of study methods and guidance from objective expert panels.”

It’s exactly the kind of outside scrutiny that Tennessee legislators are so resolutely avoiding.