From Citistates by Neal Peirce:

Jeff Speck’s new book, Walkable City, starts with a chilling quote as he laments the fate of the many American cities plagued by “fattened roads, emaciated sidewalks, deleted trees, fry-pit drive-thrus, and 10-acre parking lots.”

Speck has seen a lot of urban disasters in his career advising cities on their development choices. But the thrust of his book is anything but downbeat. Rich rewards, he argues, await cities that move to tame traffic and put pedestrians first, create attractive streetscapes, mix uses, foster smart transit and create unique, quality places. In other words, truly walkable places.

Today only a handful of American cities are making all those moves correctly – Speck mentions New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle, with Denver and Minneapolis close runners-up.

But the formula of those top cities is precisely what today’s “millennials” – born after 1981 – vastly favor: urban communities with active street life, entertainment and stimulation. As demographer William Frey puts it, “A new image of urban America is in the making. What used to be white flight to the suburbs turning into ‘bright flight’ to the cities.” It needn’t be just the millennials: “Empty nesters” (the vast, post- World War II generation) include millions tired of maintaining their suburban homes and ready, in many cases, to opt for walkable, livable communities.

So opportunities for cities are exciting. However, Speck argues, this means reining in specialists who don’t see the whole city’s needs. He singles out school departments that push for larger facilities instead of cheaper-to-maintain neighborhood schools. Ditto public works departments that insist neighborhoods be designed principally around trash and snow removal. He reserves special criticism for transportation departments that keep pushing wide roadways to let traffic move more rapidly – roadways so big and dangerous they trigger vast numbers of serious accidents (adding to America’s world-leading total of 3.2 million traffic fatalities).

The nation’s sprawling development patterns mean autos get used not just for long commutes but for rounds of small daily errands. Vast wealth flows out of communities to pay for gasoline. Sedentary, auto-dependent lifestyles exacerbate obesity levels that throw a dark shadow over our national future.

The solution Speck carries to cities: “Put cars in their place.” Discourage big new roads. Tear down obsolete urban freeways. Recognize that “free” or low-cost streetside and employer parking is paid for in taxes, goods, meals or services paid for by everyone, drivers or not. Stop minimum parking requirements for office, shopping and housing complexes, he says, because they just trigger more costs and sprawl. Put subsidies instead into public transit – the golden complement to walking.

Speck favors welcoming cars (as long as they pay a fair parking price) on shopping-area streets. They bring customers and real income to cities. But for vibrant street life, he advocates pushing ugly open-air parking lots and garages some blocks away from major shopping areas.

But for a truly walkable, accessible and friendly American streetscape, Speck adds two other key factors: trees and bikes.

Why trees? They add loveliness and pleasure to walking, at maturity even a cathedral-like street canopy. They are nature’s best shade providers. They reduce temperatures in hot weather – more vital than ever as global warming advances. They significantly increase property values. They absorb tailpipe emissions, cleansing the air. They slow cars, meaning fewer life-threatening accidents. And they absorb significant amounts of rainwater, reducing the threats of fresh- and sewage-water commingling in storms.

Small wonder Speck inveighs against traffic engineers who want to remove street trees for fear cars will crash into them.

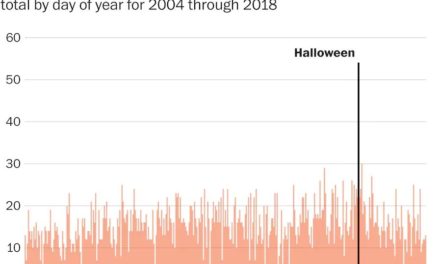

And bikes? Speck argues that “cycling has got to be the most efficient, healthful, empowering, and sustainable form of transportation there is.” With the same amount of energy as walking, a bicyclist can travel three times farther. Bike commuters get the exercise car drivers don’t. And happily, city bike riding is on a dramatic upswing right.now.

I subscribe without reservation to Speck’s bicycle pitch – perhaps because, like him, I live in Washington and have been cycling all over town for several decades. Like him, I enjoy the fresh air, the exercise and easily beating auto (and often even subway) travel time.

To be sure, Washington is especially bike-friendly: One finds parks, the National Mall’s roadways or quieter streets to avoid the heaviest vehicular traffic. Now an enlightened city government is installing bike lanes – some of them especially well-protected from traffic by vertical plastic posts – all around town.

From New York, Minneapolis, Portland, Tucson and other cities, Speck amasses evidence that biking is less dangerous, reduces accidents and saves more money than popularly thought.

Could we really have less motorized, calmer, quieter, truly livable global cityscapes? Two feet, on the ground or on pedals, may be our best formula ever – and now.

From the Big Fix:

(I can’t say that Jeff and I know each other well, but we’re friends, and I like him a lot. I’m listed in the acknowledgments, and one of my articles is cited in the narrative. I previously reviewed The Smart Growth Manual, which Jeff co-authored with Andres Duany and Mike Lydon.)

Here are the author’s ten steps of walkability, with a memorable line from his description of each:

1. Put cars in their place. (“Traffic studies are bullshit.”) Startling quote, no? Jeff believes, and I tend to agree, that a car-first approach has hurt American cities. This is in part because traffic engineers too often have failed to acknowledge that increased roadway traffic capacity can lead to more, not fewer, cars on the road. The resulting phenomenon of “induced demand” results in unanticipated consequences not only for traffic on freeways but especially in neighborhoods and downtowns, where streets are sometimes treated not as critical public spaces for animating city life but as conveyances for motor vehicles. Jeff generally supports congestion pricing, but cautions that we must be very careful about assuming the merits of pedestrian-only zones. (I think there are also circumstances where we must be very careful about congestion pricing, which I’ll discuss below.)

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Richard Masoner

2. Mix the uses. (“Cities were created to bring things together.”) The research shows that neighborhoods with a diversity of uses – places to walk to – have significantly more walking than those that don’t. Jeff makes the point that, for most American downtowns, it is housing – places to walk from, if you will – that is in particularly short supply. He also points out, quite correctly, that for most (still-disinvested) downtowns, affordability is not much of an issue, because relatively affordable housing is all there is. For those booming downtowns susceptible to gentrification, he recommends inclusionary zoning and “granny flats,” or accessory dwelling units.

3. Get the parking right. (“Ample parking encourages driving that would not otherwise occur without it.”) As do many progressive city thinkers, Jeff points out that we have a huge oversupply of underpriced parking, in large part due to minimum parking requirements for buildings and businesses. A side effect is that adaptive reuse of historic properties can be discouraged, because there isn’t sufficient space to create parking required for the buildings’ new uses. Jeff recommends consolidated parking for multiple buildings and businesses and higher prices, especially for curb parking, and shares a number of successful examples.

4. Let transit work. (“While walkability benefits from good transit, good transit relies absolutely on walkability.”) Jeff cites the disappointing experience of light rail in Dallas as an example of what not to do to support transit: insufficient residential densities, too much downtown parking, routes separated from the busiest areas, infrequent service, and a lack of mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods near the stops. Jeff recommends concentrating on those transit corridors that can be improved to support ten-minute headways, and working there to simultaneously improve both the transit and the urban fabric. Quoting transportation planner Darrin Nordahl, Jeff also reminds us that public transportation is “a mobile form of public space,” and thus should be treated with respect and made pleasurable. Amen to that. (For the opposite, see my 2010 frustration with the deterioration allowed to the Washington Metro.)

5. Protect the pedestrian. (“The safest roads are those that feel the least safe.”) Here again, it comes back to driving. Jeff asserts that roadway “improvements” that facilitate car traffic – such as wider lanes or one-way streets – encourage higher speeds; thus, we should instead use narrow lanes and two-way streets. Intriguingly, he argues – as have other new urbanists – for stripping some roadways of signage and mode delineation. The idea is that, if drivers feel they might hit someone or something, they really will slow down or change routes. Jeff supports, as I do, on-street curbside parking, because it buffers the sidewalk from moving vehicle traffic.

6. Welcome bikes. (“In Amsterdam, a city of 783,000, about 400,000 people are out riding their bikes on any given day.”) This step is only minimally about walkability, except for the point that bike traffic slows car traffic. It’s all about making cities more hospitable to cycling, which many U.S. cities are now doing. Although the drivers complain, both the research and my personal experience as a driver suggest that car traffic isn’t really inconvenienced much if at all when the addition of cycling infrastructure is thoughtful. Jeff does discuss the very interesting point that some experienced cyclists actually prefer riding in the main roadway rather than in a designated lane. Personally, if I’m on a busy downtown street, I’d rather have a dedicated lane; otherwise, I’d probably prefer to have full access to the road.

7. Shape the spaces. (“Get the design right and people will walk in almost any climate.”) Much as I liked this book, I’ll admit to wondering when, if ever, my urban designer friend was going to get around to urban design. This chapter is mostly about providing the sense of enclosure we need to feel comfortable walking. And, once again, the main villain is the car, this time in the form of surface parking lots along the walkway. But Jeff also takes some shots at blank walls (correctly) and look-at-me architecture (I somewhat, but not entirely, agree). He believes, as I do, that the amount of density to support good city walkability does not necessarily require tall buildings.

8. Plant trees. (“It’s best not to pick favorites in the walkability discussion— every individual point counts— but the humble American street tree might win my vote.”) Even though street trees correlate with fewer automobile accidents, many public transportation agencies seek to limit them because they believe they interfere with visibility. But Jeff points out that, in addition to contributing to auto safety, trees provide myriad public benefits, including natural cooling, reduced emissions and energy demand for air conditioning, and reduced stormwater pollution.

9. Make friendly and unique [building] faces. (“Pedestrians need to feel safe and comfortable, but they also need to be entertained.”) Of the ten steps, this is the one most about design, or at least the most about design of things other than roadways. For me, it evoked Steve Mouzon’s wonderful theory of “walk appeal,” holding that how far we will walk is all about what we encounter along the way. Stores and businesses with street-level windows help (meaning that most banks and drugstores don’t), as does disguised or lined parking, vertical building lines, and architectural details. Jeff isn’t so kind to parks, though, or green infrastructure designed to absorb stormwater. (I respond below.)

10. Pick your winners. (“Where can spending the least money make the most difference?”) The subtitle here could well be, “in the real world, you can’t do everything.” True enough. Jeff argues for focusing on downtowns first, and on short corridors that can connect walkable neighborhoods.

I mentioned above that there really isn’t as much about design in this very good book as one would expect from an author whose business is design. In that sense, it reminds me of my good friend David Dixon, with whom I have done more co-presentations at various conferences than I can count. David is an accomplished architect and planner; I am a lawyer. Yet, almost inevitably, in our presentations I talk about design that I believe is good for the environment, and David talks about assembling the political will to get it done.

Walkable City is like David’s presentations. It’s really a political text about why he believes we need to do these things, the objectives we should strive for (rather than the design solutions), and the obstacles that stand in the way, which he debunks one by one. There is not a single visual image in the book, and really only a handful of verbal descriptions of successful walkable places. This book is intended to motivate more than to illustrate.

Walking versus driving

The book’s opening chapter, before Jeff gets into the ten steps, is devoted to the rapidly increasing demand for walkable places and to an indictment of our car-oriented cities, which “have effectively become no-walking zones.” A “public realm that is unsafe, uncomfortable, and just plain boring” will not work for creative young people, he says, because they value a pedestrian culture that, among other things, creates opportunities for chance encounters that turn into friendships. Indeed, as others (including myself) have pointed out, the entry of the millennial generation into the housing market at the same time that baby boomers are retiring is dramatically strengthening the market for walkable places.

Boston. Photo by Kaid Benfield

To become competitive in the new marketplace for the best and brightest, cities must respond:

The conventional wisdom used to be that creating a strong economy came first, and that increased population and a higher quality of life would follow. The converse now seems more likely: creating a higher quality of life is the first step to attracting new residents and jobs.

Vancouver and Portland, Jeff argues, are among the places that are doing just that.

There’s a subtext to the book that I am not entirely comfortable with but that comes through strongly: if we just stop making driving so convenient, easy and inexpensive, people will do less of it and walk more. Put another way, making driving less convenient, more difficult, and more expensive will be good for walkers and for cities. Sure, there are more politically skillful ways of phrasing it, but I think it’s undeniable that there is a sort of ideology and, in some circles, even hostility forming around this belief (“Cars suck” was the way one of my Facebook friends put it. “Has a place ever been made better by making it easier to drive to?” chimes another, rhetorically.) There are losers as well as winners in this approach to walkability.

Saying I’m not entirely comfortable, by the way, does not mean that I entirely disagree. It’s all about finding the right balance and the answers, for me at least, aren’t always clear.

Parks and greenery

I do disagree with some of the suggestions in the book about greenery and parks, where I think Jeff is too dismissive. In a passage headlined “Boring Nature,” he concedes that green spaces are “necessary” before adding “but they are also dull.” “Verdant landscapes do not entertain.”

To suggest that parks discourage walking is to ignore the experience of the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, Russell Square in London, and St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin, to name three of my very favorite urban places. I don’t even want to think about Washington without Rock Creek Park, and I’m sure a lot of San Franciscans and New Yorkers feel the same way about Golden Gate and Central Parks. In downtown D.C., I will go out of my way to walk through one of our green squares while running an errand. I believe we need respite and calm in cities as much as we need liveliness.

Do some parks do a poor job of it? Oh, yeah. Just read my essay on DC’s National Mall for my thoughts about the ones that get it wrong.

Beyond parks per se, I disagree strongly with Jeff’s dislike of green infrastructure to reduce stormwater pollution:

Current impulses to make our downtowns more sustainable by filling them with pervious surfaces, prairie grass, and the latest craze—“rain gardens”— threaten to erase one of the key characteristics that distinguishes cities from the suburbs that remain their principal competition.

The way I see it, what these things “erase” is mostly mundane or ugly concrete. Moreover, they accomplish some important things besides just looking pretty. First, these techniques help prevent water pollution and combined sewer overflows, something Jeff rightly expresses concern about in his chapter on trees. Second, even the book he co-authored, The Smart Growth Manual, advocates permeable pavement to control stormwater, as do a growing number of urban scientists and thinkers. Third, because these things can be done very attractively and in ways highly compatible with city fabric, they can raise property values, even if you’re not the kind of person who values nature intrinsically.

Courtesy of Montgomery Planning

I actually doubt we have much real disagreement on these things; over an appropriate beverage Jeff and I would probably come to a great deal of agreement on which kinds of green belong where. I definitely agree with the starting premise that cities should be cities and rural land and wilderness should be rural land and wilderness. That’s one of the reasons I abhor the “new towns” that many otherwise progressive architects and planners are all-too-willing to plop down in the countryside when a big developer comes calling.

For me, the test of any city greening is whether or not it supports (rather than displaces) urban density and function. (I disagree with those who espouse the oxymoronic “agrarian urbanism,” or want to demolish buildings in disinvested cities to replace them with 50-acre farms. Smaller “farms” and gardens, though, can be great because they can support city life.) One of the points I would try to make over that beverage would be that different approaches work in different cities and cultures. Rightly sized and designed green infrastructure and parks are among the things that make cities possible in the 21st century.

I was a little surprised not to see more in Walkable City about street connectivity, which Ewing and Cervero’s exhaustive synthesis of transportation research found was the single most important determinant (among those analyzed) of how much walking takes place in a neighborhood. Connectivity shortens distances, making purposeful walking more attractive. Jeff does espouse small city blocks, which gets close to connectivity but isn’t quite the same thing.

Congestion can be good

Before closing, here’s why I think congestion pricing can be complicated: many American cities need more, not less, congestion. Suburban sprawl and the flight of people and investment out of downtowns in the late 20th century made a mess of things. Some central cities, like Washington, have started to grow again, thank goodness. But even D.C. has a population 23 percent below the 1950 level. Others, like St. Louis, Pittsburgh and Buffalo, remain far below their once-thriving levels and have yet to rebound.

The most commonly discussed form of congestion pricing is called “cordon pricing,” under which drivers are charged for entering downtown at certain times of day. It works in London, and might even work in New York, cities whose downtowns are so strong that they can withstand being taxed in a way that their suburbs are not. But the last thing that still-recovering downtowns need is to give people and businesses another reason not to go there. Besides, here in D.C. and I suspect in many other places, the suburban roadways are far more congested than those in the city. This needs some more thought and analysis before those of us who care about cities seize on it as a solution for everywhere.

I could say even more

There is so much more in the book that I wish I had more time and space to relate. (I’d love to quibble about grammar and syntax, too, preferably over a second round of that beverage I mentioned earlier.) My sense is that Jeff, like I have on occasion, pretty much poured at least a little bit about everything he knew on the subject into this one volume, making it rich with interesting detail.

The bottom line is that Walkable City is very good indeed, a worthy addition to the canon of urban thinking. The subject matter is critical, and Jeff is a very good and entertaining writer who keeps his reader engaged. For those of us who think about cities for a living, this well-annotated treatise can help organize our thoughts and point us to helpful research and opinion. For those outside the field but in a position to do something, it summarizes some of the best thinking on what to do to tame the car culture and make cities more walkable. For those who are merely interested or who may be curious, it will change the way you see cities. You can find Walkable City at your favorite bookstore or access it from Jeff’s website, which is pretty interesting in itself.