From Planetizen – Memphis was spotlighted in the year’s wrap-up of Tactical Urbanism success stories:

Thanks to this website and the Urban Times, 2012 began and ended with Tactical Urbanism being named one of the top planning trends of 2012. Clearly, the rapid rise of parklets, pavement to plaza success stories, and sanctioned build a better block projects are pushing this city andcitizen led movement into the mainstream.

What comes next for tactical urbanism will be the subject of an upcoming blog post, but for now I thought I’d reflect on 2012. Below you’ll find a description of five, perhaps lesser known North American examples, as well as a brief overview of the tactical urbanism work being carried out by two leading cities (hint: their names don’t end in “York” or “Francisco”).

In no particular order:

Image courtesy of Walk Your City.

Guerilla Wayfinding: Walk Your City

Last winter urbanist-entrepreneur Matt Tomasulo put his city on the tactical urbanism map with an intervention called Walk Raleigh. Without permission, Matt and a few friends posted simple pedestrian wayfinding signs in downtown Raleigh. In addition to directional information, the signs also included time-to-destination (minutes) and QR codes. A pragmatic and relatively soft spoken guy, Matt said in this Huffington Post article that the project was “just offering the idea that it’s OK to walk.”

The action-oriented approach to implementation quickly spread across the Internet, including garnering attention from the BBC. After a few weeks of praising the initiative and handling media requests, the City had to remove the signs because they were technically illegal. However, all the positive attention seemed to motivate the City Council to quickly create a sanctioned wayfinding ‘pilot project’ that allowed the the inexpensive but durable signs to be re-posted.

As an open and free platform, Walk Your City efforts have recently popped-up in Dallas, Miami, Blacksburg, Rochester, New Orleans, and elsewhere.

Image courtesy of Team Better Block.

Open Streets: Síclovía/Build a Better Block

From nine initiatives in 2006 to more than 80 in 2012, the North American open streets movement has exploded in the past few years. Measured against other successful tactics we’ve researched, open streets even surpasses the increasingly rapid adoption of parklets.

While there are dozens of successful open streets programs in cities large and small, San Antonio’s Síclovía definitely deserves some shine. Rolled out in October 2011 to creatively combat obesity, the 2.2-mile pilot initiative drew an impressive 15,000 people to the streets, which gave organizers confidence to follow through with another initiative.

In March 2012, Síclovía utilized the same route but also added a Build a Better Block initiative (another rapidly scaling tactic) so that people could physically interact with and understand a “complete street.” According to the Better Block team, more than 80 volunteers created cafes, pop-up shops and art galleries, kids’ art spaces, outdoor food courts, wayfinding signs, benches, landscaping, bike lanes, temporary reverse angled parking, and a functioning rain garden. An estimated 45,000 enjoyed Síclovía as a platform for innovative placemaking, social exchange, and public health. Great job, San Antonio.

Image courtesy of Sten & Lex.

Pre-vitalization: Living Walls

In 2009 the late Tony Goldman commissioned some of the world’s best street artists to transform the perception, and ultimately, the trajectory of Miami’s once forlorn Wynwood neighborhood. The story of what has happened since is impressive and relatively well known.

Discussed less frequently, however, is the impact sanctioned street art is having in other US cities. Atlanta, for example, doesn’t have the tradition of street art like New York or Los Angeles, but is gaining a reputation for fusing art and urbanism with the annual Living Walls conference. Launched on a shoestring budget in 2010, Living Walls pairs world-class artists with property owners looking to combat blight and attract investment with an enhanced sense of place. This past August Living Walls included block parties, bike tours, film screenings, and panel discussions debating art, urbanism, and gender (2012 artists were all women).

Living Walls maintains an heir of DIY cool and is not without controversy, but is clearly moving from margin to center as the city’s cultural establishment increasingly supports its role in putting Atlanta at the center of the American street art movement.

Image courtesy of Mike Lydon.

Pop-Up Town Hall: Imagining North Adams

Not just the provenance of large urban centers, tactical urbanism is often more powerful in small towns where less bureaucracy stands between the development and implementation of good ideas. Enter Jen Krouse, the lead instigator of a three week-long “festival of ideas and projects” called Imagining North Adams. For a town of 13,000, Jen brought national speakers to a storefront on Main Street, which was given over to her as part of a Down Street Art vacancy activation intiative.

As one of 500 lucky participants, I was treated to a veritable tactical urbanism playground: pop-up galleries, an experimental back-in angled parking trial (image above), multiple swings hanging from a roadway overpass, and a homespun Mass MOCA bike sharing system, to name but a few. Unfortunately, I missed the annual Eagle Street Beach Party, which transforms a downtown street into a temporary recreational oasis (for the record, the Eagle Street beach predates the famed Paris-Plage). To close the festival, participants demonstrated the potential of an underutilized parking lot by building a “StrEATing” cafe, which quickly inspired owners of an adjacent bar to plan similar activation projects in the space. If nothing else, tactical urbanism is about helping others seeing things differently.

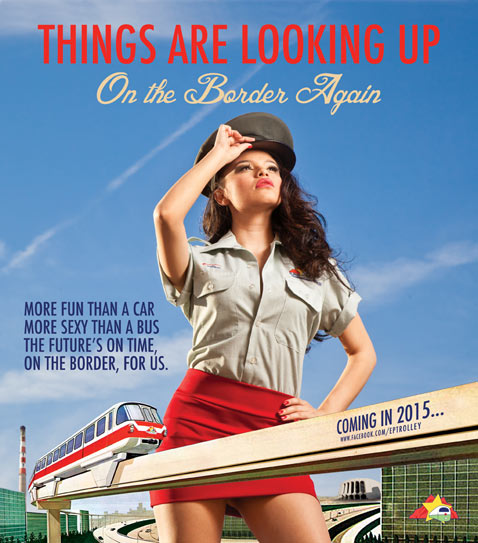

Image courtesy of The Transnational Trolley Project

Future-tising: The Transnational Trolley Project

“If you can’t imagine a better future, you can’t have a better future,” says artist and urbanist Peter Svarzbein, the creator of El Paso’s Transnational Trolley Project. Using his MFA thesis as an opportunity to remind El Pasoans of their once great international streetcar system, Svarzbein worked with two dozen artists from El Paso and Juarez to fashion a vintage PCC streetcar out of 2000+ citizen portraits. This specific piece was accompanied by a fake advertising campaign (see above) heralding the return of transit to the Texas border. The project quickly bolstered a citywide conversation already underway via the ongoing Plan El Paso, an award winning comprehensive plan, which called for…yes, more transit. Svarzbein’s effort, which I call “future-tising,” was greatly validated and bolstered in May of 2012 when the Texas DOT awarded El Paso with a $90 million dollar grant to implement a new downtown streetcar line.

This winter Svarzbein is offering up another tactical urbanism project: the downtown Purple Pop-Up gallery. “Bigger projects are great, but this creates an urban fabric that is more sustainable for Downtown,” says Svarzbein.

Two Cities to Watch

While the citizens and city leaders of San Francisco and New York continue to bolster their reputation as tactical urbanism hubs, several other cities began playing catch up in 2012, including Boston and Memphis.

Boston

I love Boston, but it hasn’t exactly been viewed as a hotbed of municipal innovation for quite some time. I think that all changed this year. From the establishment of the nation’s most proactive food truck program, to rolling out a mobile city hall, to launching Circle the City and a new parklet program, 2012 is the year Boston embraced tactical urbanism. The city also continues to connect physical innovation with a myriad of digital efforts coming out of the Office of New Urban Mechanics. In a recent Business Insider article, CIO Bill Oates had this to say about Boston’s efforts: “…we believe that government isn’t about providing data, government’s about providing results and so that’s how we think about this.”

Memphis

As in many other cities, the concept of tactical urbanism was introduced to Memphis through a better block inspired project called A New Face for an Old Broad. Organized in 2010 by local business owners and activists, a few largely vacant commercial blocks along Broad Avenue served as a temporary laboratory for better urbanism. The weekend long intervention, which brought an estimated 15,000 people to the area, has resulted in an estimated $8 million in private investment. The temporary DIY cycle track built over that weekend, which remains in place to this day, also helped Memphis leverage a Green Lane project grant to permanently construct innovative bikeways, including the one on Broad Avenue.

Learning from the enormous sucess of A New Face for an Old Broad, the Mayor’s Innovation Delivery Team hosted a Tactical Urbanism Salon in 2012 and is now using tactical urbanism as the middle part of a “Clean it. Activate it. Sustain it.” strategy for neighborhood revitalization. Indeed, in November numerous partnering organizations and an army of volunteers launched MEMFix. Using several of the tactics already highlighted above, the intervention brought thousands to the Crosstown Arts neighborhod to test out ideas for that area’s rejuvenation. Said Mayor AC Wharton: “Too often, cities only look to big-budget projects to revitalize a neighborhood. There are simply not enough of those projects to go around. We want to encourage small, low-risk, community-driven improvements all across our city that can add up to larger, long-term change.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.