From Better Cities and Towns:

I live in a city that is currently updating its Community Plans. This is an historically difficult planning job because Community Plans transcends both broad policy statements (such as the amorphous “New development should be in harmony with surrounding development…”) and specific development regulations (“Front yard setbacks shall be 25 feet deep from property line…”). An issue with updating Community-scaled plans is the personal sentiment people feel for their homes and the difficulty we have in expressing such emotion within conventional 2D planning documents. The source of most conflicts and confusion I see occurring during these updates is due to the confusion over the scale and size difference of a ‘community’ versus a ‘neighborhood’ unit.

A community is defined as, “a group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common.” Many places have different communities inhabiting them, such as an elderly, or arts, or ethnic community living and/or working in close proximity to each other. Even the Internet can be considered a place inhabited by many diverse communities. So the scale, parameters, and character of a community-scaled planning effort is difficult to define.

Usually, community planning areas are defined by political boundaries, or historic development plats and, in some deplorable cases, old insurance red-lining practices that gave a city its initial zoning districts. This being the case, I contend that the neighborhood unit is a better tool to define, plan, and express policies and regulations necessary to preserve, enhance and, yes, build great places.

The neighborhood is a physical place — varied in intensity from more rural to more urban — that many different communities inhabit. At its essence, whether downtown, midtown or out-of-town, its health and viability (in terms of both resilience and quality of life) is defined by certain basic characteristics. Easily observable in neighborhoods that work, these characteristics have been articulated a variety of ways over the years — most notably for me by Andrés Duany and Mike Stepnor. Combined, they form what I like to call the 5 Cs:

1. Complete

Great neighborhoods host a mix of uses in order to provide for our daily need to live, work, play, worship, dine, shop, and talk to each other. Each neighborhood has a center, a general middle area, and an edge. The reason suburban sprawl sprawls is because it has no defined centers and therefore no defined edge. Civic spaces generally (though not always) define a neighborhood’s center while commerce tends to happen on the edges, on more highly traffic-ed streets and intersections easily accessible by two or more neighborhoods. The more connected a neighborhood is, the more variety of commercial goods and services can be offered, as not every neighborhood needs a tuxedo shop or a class ‘A’ office building.

2. Compact

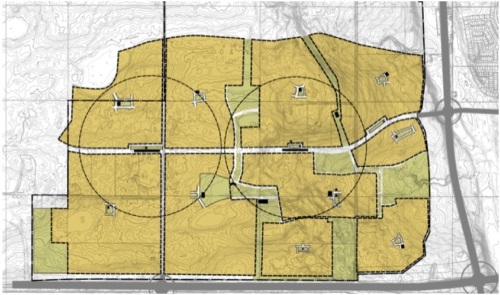

The 5-minute walk from center to edge, a basic rule-of-thumb for walkability, equates to approximately 80 to 160 Acres, or 9 to 18 city blocks. This general area includes public streets, parks, and natural lands, as well as private blocks, spaces and private buildings. This scale may constrict in the dead of winter and/or heat of summer, and expand during more temperate months. Compactness comes in a range of intensities that are dependent upon local context. Therefore, more urban neighborhoods, such as those found in Brooklyn, are significantly more compact than a new neighborhood located, for example, outside Taos, New Mexico. Remember, the ped-shed is a general guide for identifying the center and edge of a neighborhood. Each neighborhood must be defined by its local context, meaning shapes can, and absolutely do, vary. Edges may be delineated by high speed thoroughfares (such as within Chicago’s vast grid), steep slopes and natural corridors (as found in Los Angeles), or other physical barriers.

3. Connected

Great neighborhoods are walkable, drivable, and bike-able with or without transit access. But, these are just modes of transportation. To be socially connected, neighborhoods should also be linger-able, sit-able, and hang out-able.

4. Complex

Great neighborhoods have a variety of civic spaces, such as plazas, greens, recreational parks, and natural parks. They have civic buildings, such a libraries, post offices, churches, community centers and assembly halls. They should also have a variety of thoroughfare types, such as cross-town boulevards, Main Streets, residential avenues, streets, alleys, bike lanes and paths. Due to their inherent need for a variety of land uses, they provide many different types of private buildings such as residences, offices, commercial buildings and mixed-use buildings. This complexity of having both public and private buildings and places provides the elements that define a neighborhood’s character.

5. Convivial

The livability and social aspect of a neighborhood is driven by the many and varied communities that not only inhabit, but meet, get together, and socialize within a neighborhood. Meaning “friendly, lively and enjoyable,” convivial neighborhoods provide the gathering places — the coffee shops, pubs, ice creme shops, churches, clubhouses, parks, front yards, street fairs, block parties, living rooms, back yards, stoops, dog parks, restaurants and plazas — that connect people. How we’re able to socially connect physically is what defines our ability to endure and thrive culturally. It’s these connections that ultimately build a sense of place, a sense of safety, and opportunities for enjoyment… which is hard to maintain when trying to update a community plan without utilizing the Neighborhood Unit as the key planning tool.

Howard Blackson is principal, director of planning with Placemakers, a planning, coding, marketing, and implementation firm. This article was also published on PlaceShakers and NewsMakers.