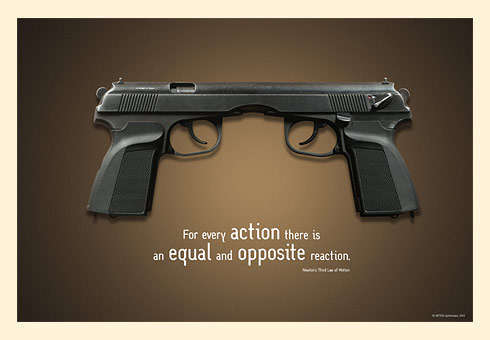

The business of the Tennessee Legislature is enacting laws, but the predominant ones on display in Nashville often are the law of unintended consequences and Newton’s Third Law of Motion: every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

That was certainly the case with proposed bills by some suburban Shelby County legislators about school consolidation and annexation. Both ended up producing exactly what the legislators were trying to prevent. One propelled the vote in Memphis to merge the city and county school systems and the other started the process for Memphis to annex eastern Shelby County.

Both are classic examples of why the legislative process, as it is now practiced, is characterized by lack of communications, an emphasis on political one-upmanship, and the use of divisiveness as political strategy. It may be smart, albeit cynical, politics for some, but it rarely produces smart public policy because it is built on dividing Shelby County into “them and us” and on fanning anti-Memphis fires.

Consequences, Unintended or Otherwise

That’s what makes the outcomes on schools and annexation so ironic. After years of chasing special school district status for Shelby County Schools, suburban legislators set out to make it happen, an action which moved Memphis City Schools to surrender its charter and create a countywide school district. Making it even more ironic was that the merger movement came in the wake of the resounding defeat outside Memphis of government consolidation, which had it been approved, would have protected the two school districts.

The same unintended consequences came into play in this year’s annexation controversy. After some suburban legislators penned a bill to keep Memphis from exercising their legal rights to annex eastern Shelby County, City of Memphis put a target on the Gray’s Creek and Fisherville areas for immediate annexation. Without the state legislators’ action, the area would not have been annexed in decades, if ever.

Some members of the Wharton Administration and City Council had begun to question long-held city attitudes about annexation. Past practice has been for Memphis to chase people and revenues and gobble up county land as part of the ever expanding city limits. The annexations propped up the budgets of city government, but the cost was paid by Memphians who were effectively subsidizing the decline of their own city.

Not Dense Enough

It’s difficult to look at the hollowing out of middle class Memphis neighborhoods, the deterioration of neighborhood infrastructure, and the climbing costs of city services and not wonder if the annexation at all costs policy might have been a contributing factor.

The population today within the 1970 city limits of Memphis is 28% less than it was then. In other words, 124,348 people within the 217.4 square miles of the 1970 Memphis borders are no longer there.

When the 20th century dawned, Memphis covered a grand total of 18.5 square miles with a density of 7,125. By 1970, it was at 178 square miles (almost a doubling of the size of the city since 1950 and 40 square miles bigger than today’s Atlanta). The density of Memphis now is about 2,000 persons per square mile, down from about 4,000 in 1960, about 3,500 in 1970, and about 2,500 in 1980.

Today, Memphis is bigger in land area than New York City – 346 to 305 square miles. Public services over such a massive area stretch already underfunded services even more and suggest that Memphis needs a serious debate about when big is too big and about how size matter when it undermines the effectiveness and economy of public services.

More Than Math

As happens often in government, there are no data and analysis of annexation to conclusively answer the question of what’s best for the future of Memphis. No one has tried to determine what the “real” cost of annexation is, because annexation studies were only about new revenues to be generated from the newly annexed areas and the costs of city services to the areas.

In other words, it has always been an arithmetic problem – revenues minus expenditures – to determine if the city “made” money on the annexation. Unfortunately, it was never an exercise to determine the full costs, which included the implications for inner city neighborhoods and the scenarios for all the options — annexation, no annexation, or even de-annexation.

This may run counter to American’s obsession with size as the ultimate definition of success, but perhaps, in the future, Memphis’ policy about annexations will change and its focus will shift from expanding its size with new territory to focusing its attention laser-like on improving the neighborhoods it already embraces.

Previously published as the City Journal column in the March issue of Memphis magazine.

You said “it has always been an arithmetic problem – revenues minus expenditures.”

I think that might even be too generous. I am not sure they are making decisions on data that basic, much less the “full costs” that you are discussing.

Good studies have been done in many cities around the country about costs and benefits. Some followed, many not, and many battles fought over annexation. Few cities and only selective landowners have profited from over-expansion of urban areas. Infrastructure and services are very expensive and low density development usually ends up being heavily subsidized by the denser urban development taxpayers for the benefit of a few speculators. Healthy growth can be good but people must know the difference between cancer, fat and muscle and know how to keep the arteries clean. Bigger is always better is the attitude of a cancer cell.