From Atlantic Cities:

Sunni terrorist detonates a bomb at a crowded Shiite shrine in Iraq. Political anti-Semitism is on the rise in the Russian Federation, even though most of its Jews have long-since emigrated. Millions of Central Africans have died because of the long-standing enmity between the Tutsi and Hutu peoples.

Prejudice is present in almost every community, but its levels and loci are constantly shifting. If Germany engineered the worst genocide in recorded history in the 1940s, it is a relatively tolerant place today. Lebanon, once noted for its cosmopolitanism, is much more divided now. What are the drivers of prejudice and tolerance? What makes them wax and wane?

With the help of my Martin Prosperity Institute colleague Charlotta Mellander, I calculated a Global Prejudice Index or GPI for short, based on the answers respondents provided to four Gallup World Poll questions: Is the city or area where you live a good place or not a good place to live for:

- Religious minorities

- Ethnic and racial minorities

- Gays and lesbians

- Immigrants from foreign countries

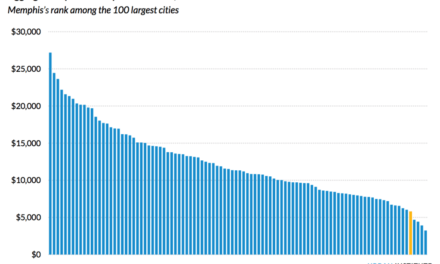

As the map shows, prejudice is strong across the former Soviet Union, through the Middle East and Africa and in Southeast Asia. Nineteen of the 50 worst-scoring countries are in the Middle East or Africa. Seventeen of the top 50, including Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Lithuania, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Belarus, are in the former Soviet Union. The Russian Federation itself ranks 14th. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Cambodia all score in the top ten, with Mongolia 12th and Vietnam 24th.

Put any one country or region under a microscope and you’ll quickly discern the uniquely local qualities of its hatreds. The Middle East has long been divided along religious and ethnic lines. The breakup of the former Soviet Union awakened dormant nationalist aspirations in places like Georgia and Chechnya. Cambodia and Thailand suffer from stark economic divides and are also traditional enemies.

Still, it’s just as important to step back and look at the bigger picture. What are the key social, demographic and economic factors underlying prejudice? What effect does prejudice have on the wealth and happiness of nations?

First and foremost, prejudice is associated with economic backwardness. With a few notable exceptions, it clusters most heavily in places that are rife with substantial economic, political, and cultural stress. Prejudiced countries also tend to be poorer and less developed. It is hard to say which causes which – whether prejudice holds development back or retarded development engenders prejudice – but the connection is clear.

Conversely, the most economically developed countries tend to be the least prejudiced. Most of Europe and North America show up pink on the map above. Canada, whose government once sought to erase every trace of its indigenous people’s cultures, is now the least prejudiced nation in the world. The United States, with its history of slavery and Jim Crow, is the fifth most tolerant. Luxemburg, Ireland, Spain, Uruguay, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand all show low levels of prejudice.

Ronald Ingelhart’s World Values Surveys have traced the close associations between economic development and open-mindedness; studies by the Peterson Institute for International Economics show a correlation between a country’s tolerance of homosexuality, its levels of globalization and the quality of its economic performance.

According to our statistical analysis, high levels of prejudice are associated with lower levels of income, less innovation and entrepreneurship and lower levels of happiness and subjective well-being. Conversely, high levels of acceptance and tolerance are associated with larger incomes, more innovation, higher human capital and happier populations.

While prejudice of any kind is problematic, prejudice against gays and lesbians is by far the most prevalent and ingrained. According to the Gallup data, an average of just 26.3 percent of World Poll respondents said their city or area was a good place for gay and lesbian people to live, as compared to 57.7 percent for immigrants, 59.3 percent for ethnic and racial minorities, and 66.9 percent for religious minorities. It also appears to be the most economically damaging. Gay-friendly places are much more prosperous than homophobic ones.

It makes intuitive sense. Places that are welcoming to different kinds of people are also likely to be hospitable to the kind of creative, out-of-the-box thinking that drives innovation and prosperity. Less prejudiced, more open-minded places benefit from their ability to tap into the talents of the whole spectrum of their population. At the same time, they are able to attract energetic and talented immigrants from across the globe.

Gauging a country’s level of prejudice also provides unique insights into its economic potential. Consider the emerging BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). Two of them, Russia and India, are beset by high levels of prejudice. (There is not enough data to adequately assess China). But Brazil is both racially tolerant and open to gays and lesbians (its GPI is on par with the United Kingdom). This will give it a substantial edge over its peers when it comes to attracting global talent.

The GPI can help us assess how the growing competition among Asia’s economic and financial centers – Shanghai, Tokyo, Singapore, Seoul and Hong Kong – is likely to play out. Of those centers, Hong Kong has the lowest level of prejudice. This not only gives it an advantage over its regional peers, it also positions it to compete with established business centers like New York and London.

The bottom line? Prejudice is not just morally reprehensible, it’s economically punishing as well.