From Placeshakers:

By the early to mid 1970s, something was wrong with rock and roll.

It no longer fought the system. Worse than that, it had become the system. Bloated. Detached. Pretentious.

Performer and audience, once fused in a mutual quest to stick it to the man, now existed on separate planes – an increasingly complacent generation sucked into the service of pomp and circumstance. And the shared experience of joyful rebellion? Replaced by pompous, weed-soaked, middle-earth mysticism.

Rock and roll needed to get back to basics. What country pioneer Harlan Howard characterized as “three chords and the truth.” Enter punk rock.

New Urbanism Wins the War

Missing the connection to urbanism? Stick with me. What sent me down this metaphorical rabbit hole were mounting suggestions that the war for America’s built future is over. And New Urbanism won.

My colleague, Howard Blackson, said as much in a recent blog post. But the most compelling evidence can be found in just about any municipal comp plan from anywhere in the U.S. Even ones written by people who’ve never even heard of the New Urbanism or, better yet, consider it some sort of threat to our sovereign liberty.

Take a look inside at the concepts being adopted and the words employed to describe them. Town and neighborhood centers. Walkability. Mixed-use. Form. Housing diversity. Transportation choice.

Not only is that the new language of livability, it’s also the gospel New Urbanists have been preaching for over a quarter century — now embraced everywhere you look as normative planning practice. That makes us the de facto victor in the battle for hearts and minds, even as it deprives us of our long-imagined, flag-planting, told-ya-so moment bringing the war to a poetic close.

Inch by inch, it just sort of happened. But now comes the aftermath. New Urbanists who built careers fighting the system are presently waking up to find that the new system is, well, us.

And all of a sudden, our roundabouts might as well be “Roundabout.”

20/20 Hindsight

I think I was on this charrette…

I think I was on this charrette…We should have seen it coming. In the glory days of the housing boom, developer charrettes were akin to Led Zep’s Boeing 720 “Starship” (minus the groupies and drugs, as far as I know). Luxury, comfort, and every creative whim not only welcomed but celebrated.

Ouch. In that context, our frequent argument over whether to code something four stories or five, despite a market that may never support more than a story or two, suddenly takes on the overreaching tones of an eight minute guitar solo.

And our greenfield TNDs? While certainly beautiful, functional and neighborly, many remained so connected to auto-intensive patterns of commuting and consumption that, in retrospect, they were the creative equivalent of a free-form jazz exploration in front of a festival crowd.

Santana Row. Beautiful, but can we build it in the future?

Santana Row. Beautiful, but can we build it in the future?Finally, there’s our master planned town center development schemes which, like Genesis’ “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway,” dutifully satiated our desire to be entertained at a grand scale. But all too often, behind the curtain, were balance sheets so bloated that fostering the incubation of small business start ups or service sector housing, the bedrock of sustainable economics, remained flat-out impossible.

Yes, those plans reflected the optimistic tenor of the times — not to mention the evolution of the century’s most influential design movement — but they were also the beginning of the end. Call it New Urbanism’s operatic collaboration with the London Philharmonic.

Where’s punk rock when you need it?

Meet the New Boss

As it turns out, it’s been kicking around the underground for a while now. A new breed of back-to-basics urban troubadours, banging out songs of incremental infill, architectural temperance, sustainable economics, and design tuned to humans across the social spectrum. Here are three:

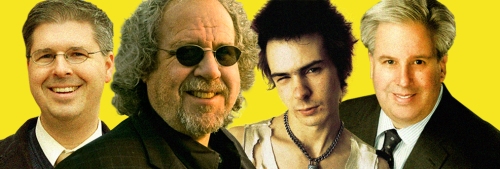

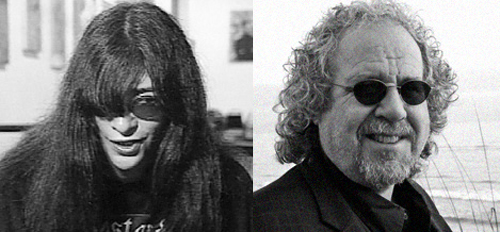

Bruce Tolar, New Urbanism’s Joey Ramone

Like Joey Ramone, Bruce Tolar is shaggy haired and roughly 20 feet tall yet, despite that, friendly and unthreatening. An architect in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, we’ve written about his work before, here and here, but the Cliff Notes version is this: Bruce participated in the post-Katrina Mississippi Renewal Forum, where the idea of the Katrina Cottage was born, and has since gone on to be one of the most active, put-yer-money-where-yer-mouth-is champions of small scale, cottage infill as a catch-all solution for workforce housing, business incubation, and aging-in-place.

Cottage Square, the embodiment of his ideas, speaks a particular brand of truth because it emerged organically over time. “Some people collect stamps,” he explains. “I collect cottages.”

The Cottages at Oak Park, adjacent and connected to

The Cottages at Oak Park, adjacent and connected toBruce Tolar’s Cottage Square.

Through a combination of strategy, good fortune and happenstance, a slew of the movement’s proof-of-concept cottages, 14 in all, have come to reside on Tolar’s property. The original MRF Cusato Cottage that debuted at the 2006 International Builders Show in Orlando. The Lowes kit cottage. Two from the Mouzon Katrina Cottages collection. The DPZ cottage. Even a row of MEMA emergency houses. Together they form a modest, infill proto-neighborhood of both commercial and residential structures, walking distance from primary conveniences and a short bus or bike ride to the finest downtown on the Mississippi coast.

More importantly, they’ve also proved scalable, having since inspired an adjacent development of another 30, now fully occupied, rental units. All in all, over 40 cottages occupy the lush, four acre site.

While not necessarily tearing down the walls of the establishment, Tolar’s efforts expose an exciting and empowering alternative to the conventional wisdom of the old guard — that workforce housing is housing of last resort; that it can’t be desirable when produced at a reasonable cost; that it can’t add aesthetic and economic value to a community; that it has to be concentrated on a large scale; that it can’t be integrated with existing development; and that people won’t downsize by choice. Given the right options, they will. Happily.

Chuck Marohn, New Urbanism’s Ian Mackaye

A self-described “recovering engineer,” Chuck Marohn is on a mission. Like Ian Mackaye, he compels people — or, in this case, towns of people — to take ownership of their inherent value, follow their own path, steer clear of destructive behaviors, and become more of what they’re capable of becoming.

Some people find the blunt edge of his truth unsettling. He doesn’t care.

In his own words, here’s what’s driving him: “The American approach to growth is causing economic stagnation and decline along with land use practices that force a dependency on public subsidies. The inefficiencies of the current approach have left American towns financially insolvent, unable to pay even the maintenance costs of their basic infrastructure. A new approach that accounts for the full cost of growth is needed to make our towns strong again.”

Like parenting, his work requires tough love and the ability to tell people things they instinctively do not want to hear. It garners scores of fans for Strong Towns, the nonprofit advisory he runs from Saint Paul, Minnesota, but it can also get him in hot water. Turns out, pointing out that the emperor is wearing no clothes is an often thankless business.

Last month, Marohn was on a tear about development patterns, contrasting the economic performance and future potential of two blocks in his hometown — one with traditional, pedestrian-oriented, small lot urbanism; the other with an auto-oriented fast food franchise. There was no soppy lamenting of lost memories, no touchy-feely boosterism of “community.” There were only numbers. Numbers that don’t lie.

Long story short, the idea that we’re achieving economic gains through auto-friendly strip development is a fallacy. Instead, we’re signing our own death warrant.

Such revelations alone are enough to encourage some folks to insert their heads comfortably back in the sand, but Marohn was just getting started. He followed things up with this post taking easy aim at the consulting profession still happily suckling at the teet of delusional municipal aspirations. To him, it’s akin to professional malpractice.

You can’t stop him. He doesn’t want to help cities thrive. He needs to. Exposing the Growth Ponzi Scheme while pushing models of scale and form proven to endure without bankrupting the places we purport to care about, he doesn’t pander to his audiences. He confronts them.

It ain’t pretty, but the truth rarely is.

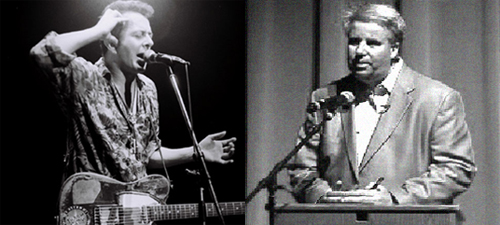

Bob Gibbs, New Urbanism’s Joe Strummer

Joe Strummer had a gift for taking aim at the system and helping people see how it wasn’t always ideal for helping them be who they wanted to be. His mantra, “The Future is Unwritten,” summarized his belief that, ultimately, things will be whatever we make of them. That we have it within our power to change our apparent destiny. To change systems.

That kind of describes retail guru Bob Gibbs.

The author of the recently published “Principles of Urban Retail Planning and Development,” Bob takes those schooled in conventional retail and reorients them for an urban future. He’s a sensei. A mythbuster. But most importantly, he’s grounded in the reality of what people want.

Bob knows our economic gravy train has ground to a screeching halt, perhaps permanently. In response, he scours our built past — when we lived in traditional, urban communities with comparatively less wealth — for models to guide the present.

He doesn’t so much seek to destroy the system as he does to subvert it in a quest for better outcomes. Here’s a dose of his pragmatism, taken from a previous interview:

“We need to make it as easy or easier to develop in city centers. Developers made the mistake of thinking that town centers had to be complicated with lots of ornamentation – fountains, clock towers, paving. Santana Row was $400-500/SF to build, requiring $40-50 rents (per foot). It’s unsustainable. They didn’t appreciate the value of urbanism. When you’re passing a strip center, you’re passing it at 40-50 MPH, so they have to make them attention getting. When experiencing urbanism on foot, it’s totally a different animal.

New Urbanism got this tag that it was more expensive to build than conventional retail. So most developers think that good urbanism is twice as expensive. Terry Shook, for example, is really good at building town centers that are the same price or less than conventional: $60/SF for office buildings that are really beautiful, while others were paying $120/SF for the shell. All four sides of the building don’t have to be brick, and it doesn’t have to have a slate roof.

If you look at great cities, when they were peaking in the 40’s and 50’s, they were simple. Great placemaking, good squares, places between the buildings were beautiful. Even street trees were rare. The older buildings in Winter Park’s Park Avenue or in Palm Beach’s Worth Avenue in Florida are often 1-story, $60/SF buildings.

Palm Beach. 1-story. Built for roughly sixty bucks a square foot. Image credit: Bob Gibbs.

Palm Beach. 1-story. Built for roughly sixty bucks a square foot. Image credit: Bob Gibbs.Cities can redevelop themselves by going back to the 20’ x 60’ lot, and selling them to small entrepreneurs who can build their own. Instead of waiting for someone who can build a $60 million project, the city can replat to the smaller lots, and sell under $50,000 each, then smaller businesses through sweat equity can build their own stores. Rosemary and part of Seaside were built this way. The only part of Rosemary that got in trouble was the large hotel, which went through a few bankruptcies. It’s a very good post-recession model. Instead of taking out a large note to build an Easton Town Center, build the streets and squares, and let the rest occur incrementally, on a small scale, as the market will bear.”

It’s Now or Never

The bloat of the housing boom is over. We’re living in a different era now — an era of new economic realities — and the relevance of the planning and development trades depends on their — our — ability to get back to the basics of urban growth and development.

It’s happening. The torchbearers profiled here reflect something real and growing and I encourage you to become a part of it. Of course, I’d never be so presumptuous as to speak on their behalf, but my gut tells me their response would go a little something like this: