From Places:

These are places we Americans know well: suburban and exurban neighborhoods, where gently curving streets are lined with single-family houses with driveways, multi-car garages, front lawns. We have been constructing these houses for decades, from coast to coast; and for decades the extensive car-dependent neighborhoods and cities they have produced have been roundly critiqued for their negative impact on natural landscapes and ecological systems, on cultural life and social relations, on energy use and personal health. For at least a generation urban design practitioners and theorists have focused on the redevelopment of suburbia; one of the most prominent recent studies is Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson’s Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs, which features case studies for up-zoning corridors, converting strip malls, reusing big box stores, etc. [1] The big-picture ideas and national movements are by now well known — transit-oriented development, New Urbanism, Smart Growth, and so on. And yet the suburban reformers, focusing almost always on the scale of systems, have rarely paid sustained attention to suburbia’s essential component, its irreducible unit — the freestanding single-family house.

Suburban development, South San Jose, CA, 2006. [Photo by Sean O’Flaherty via Wikimedia Commons]

From the modest Cape Cods of Levittown to the center-hall colonials of New England, from the bungalows of the South and Midwest to the Spanish-inflected ranches of California, these houses at once embody and perpetuate longstanding national ideas and assumptions about home ownership, land use, family life and the relationship of the individual house to its neighbors and to the community as a whole. Viewed collectively, suburban housing constitutes the most ubiquitous construction type in the United States in the last half century. At the peak of the housing boom that ended in 2006, single-family houses made up more than three-quarters of housing construction permits and housing starts; and by then the average size had ballooned to more than 2,200 square feet, and the average price topped $250,000. [2] The sustained growth in sales of ever-larger suburban homes is truly remarkable, especially given changing family structures and population demographics and the marked mobility of American life. In fact, since the postwar years, average household size has notably decreased (from 3.8 people in 1940 to 2.59 in 2000), and the population remains strikingly peripatetic (in 2009 and 2010, 12.5 percent of Americans relocated). [3] The disconnection between the rising diversity of housing needs and the monotony of housing production speaks to the tenacity of the postwar American dream — the enduring allure of the detached house with front lawn and backyard patio — as well as to the profitability of catering to these aspirations.

Suburban development, Colorado Spring, CO, 2008. [Photo by David Shankbone via Wikimedia Commons]

Outdated Dreams

That is, until recently. The accelerating decline of suburban neighborhoods from Florida to California suggests that the contradictions of the system are finally catching up with it. The Great Recession is challenging not only the economics of homebuilding but also the essence of the suburban dream. Residential construction has slowed dramatically, and yet there remains a massive oversupply of single-family houses, especially on large lots. [4] This raises a difficult question: What to do with that oversupply, with the millions of houses now in foreclosure, many deteriorating or abandoned? [5] It is possible — and no doubt to many real estate developers desirable — that once the economy revives we will simply return to home-building-as-usual. But right now we have an opportunity to rethink suburban housing: to make it responsive not to dated demographics and wishful economics but rather to the actual needs of a diversifying and dynamic population — not only to the so-called traditional households but also to the growing ranks of those who prefer to rent rather than buy, who either can’t afford or don’t want a 2,000-square-foot-plus detached house, who are retired and living on fixed incomes and maybe driving less, who want granny or nanny flats, who want to pay less for utilities and reduce their carbon footprint, and so on.

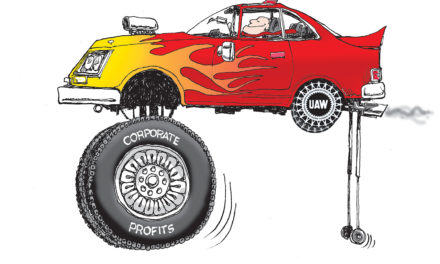

Rethinking suburban design is an enormous challenge because many suburban neighborhoods have been designed, developed and managed precisely to avoid change and limit uncertainty. Indeed, many subdivisions exude a palpable sense of stasis, even immutability, which owes not to residential construction technologies, which are relatively adaptable, but rather to the economic expectations and regulatory structures that inform their inhabitation. [6] By now these are familiar: we know that many houses function not simply as family residences but also as investment vehicles; they’re not just homes but commodities. Lightweight wood-frame designs are replicated across the country, regardless of location and climate, because they are cheap and efficient to build; often the houses are purchased to be quickly flipped, not dwelt in comfortably or solidly for years. It was indiscriminate production of this housing type that inflated the bubble and drove the economy to near collapse; yet the very policies that enabled the proliferation of these neighborhoods now render them unproductively inflexible. Large-scale social, cultural and economic changes — in family structure, household income and mobility, gas prices, home heating and cooling costs — have registered hardly at all in the built environment of suburbia.

To read more, click here.