The Bass Pro deal for The Pyramid is disturbing.

And our concern has nothing to do with the terms of the agreement.

It’s about the dependable Greek chorus of people who complain anytime Memphis pursues anything that requires city government to act like a modern, big city government. They sometimes are the same people who howl because Memphis can’t keep pace with (pick a city) but then decry any project aimed to advance our city.

It prompts ugly comments about “thieves” and “crooks” in City Hall although the authors obviously have not read any of the documents or can offer up scintilla of evidence about a hint of malfeasance. They have firm opinions about Memphis elected officials, who, if they built up a billion dollar reserve fund and suspended property taxes, would still be pilloried. It prompts incomprehensible commentaries like the politically motivated ones delivered Monday by Shelby County Commissioner James Harvey and it generates a litany of questions by people who don’t take the time to the financial reports, the market studies, and the financing plan but still manage to decide that city public officials didn’t get their questions answered.

It’s All How You Do It

Here’s what disturbs us. All of this stems from a fundamental lack of understanding about what makes cities successful today: They take risks.

That doesn’t mean that they don’t mitigate risks, but if anyone thinks that cities today should avoid anything that even has a whisper of a risk, he is wrong. It’s a curious opinion expressed by some because it often comes simultaneously with the mantra that government should act more like a business. There’s few lessons more compelling and more obvious from the private sector, just ask Fred Smith, than the need to take calculated risks.

They are taken after mounds of evidence are gathered, after teams are assembled to test theories, and after all scenarios have been assessed. No project in memory has been vetted as much as The Pyramid redevelopment. There have been numerous presentations and updates to City Council, and because of Council questions, the deal was improved and strengthened.

We learned in the first decade of this century what it looks like when city government sits on the sidelines. It took no risks. It didn’t get into the game. Lethargy came to characterize decision-making and the expansion of the economy was left to others to handle. We saw the effects. Memphis shed about 40,000 jobs, it fell to the bottom of most measurements of economic vitality, and it failed to even train workers for better jobs.

Jobs Conference Lesson

We think back to the 1981 Memphis Jobs Conference, regularly hailed as one of Memphis’ finest hours, as disparate and diverse groups of Memphians came together to listen to the smartest thinkers on economic growth and to join hands behind new initiatives designed as game changers. Speakers before the SRO audience in the ballroom at The Peabody included nationally known people like Bob McNulty, president of Partners for Livable Communities, James Rouse, pioneering real estate developer, and others.

Speaker after speaker agreed on one thing: Cities have to take risks to succeed. Playing it safe would mean that Memphis could not compete with its competitors, and from this discussion came an emphasis on logistics, tourism, stronger economic development programs, Beale Street, Convention Center Hotel, Agricenter, and other strategies.

The message about risks is even more relevant today than it was then. Now, more and more of the incentives and programs for economic growth are being shoved down to cities and their governments to provide. It means that city governments have to be as sophisticated as the economy they hope to succeed in. It means that they have to find new ways to leverage dollars with the private sector or to make investments that spark new economic activity.

It is a trend playing out in cities across the U.S. and because the recession was international in its impact, it’s also playing out in Canada where cities are embarking on much larger, much bolder projects to keep their cities competitive. There are plenty of cities that decided to rest on their laurels and have faded from economic importance, some who decided to look backward at its glorious past while ideas and power flowed somewhere else.

Risk = Innovation

As the brilliant British innovation expert Charles Leadbeater, who spoke by video conference to Leadership Memphis a couple of years back, said: “Innovation is not a theoretical activity but a very practical one. You have to try, fail a bit, learn, adapt, try again. That means that organizations and cities that want to innovate have to take risks. They also need a way of committing resources to ideas to scale them up. It is not for the faint-hearted.

“But the city will face huge challenges and dilemmas in the future and it may well be that the recipe it needs in the future will different from the one that got it from 1990 to 2005. You cannot build a culture of innovation in the way you build a new road.”

Or as a FedEx leader puts it, you can’t bring 1990 thinking to 2011 problems. If you do, it only means failure.

Then, there is Charles Landry, author of the much-quoted book, The Creative City, who spoke at Leadership Memphis’ annual community breakfast (now a luncheon). “Intelligent, innovative, imaginative responses to varied demands involve risk,” he said. In most organizations, especially public ones, risk is frowned upon. Aversion to risk-taking can mean that an institution has no internal R&D mechanism.”

ROI

That said, governments cannot be in the business of wild risk-taking that is not anchored on research and a process that takes risk to its most minimal levels. It seems to us that Pyramid redevelopment is the result of this kind of process. Like many decisions that involve the public sector, it is a trade-off. You may not like Bass Pro as a retailer, but its presence – as it does in every city where it locates – attracts other retailers like those pilot fish that swim in the shadow of the larger fish.

The market has already given its verdict about Bass Pro, and the developers contacting city government about the Pinch redevelopment attest to its allure.

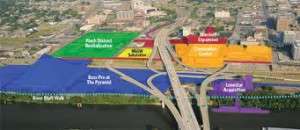

In other words, because of the new Pyramid incarnation, the Pinch Historic District will be redeveloped (renderings so far are only conceptual), Marriott Hotel is likely to be expanded, and the Memphis Cook Convention Center will get a new façade. None of it happens without Bass Pro, and even the cynics among us were converted by the opportunity to create a true convention center district so that conventioneers no longer feel like they are abandoned on an isolated island with few nearby amenities.

Mitigating Risk

As part of the deal, the Convention Center debt moves from Shelby County’s books to Memphis’ books, but its funding source does not change. It continues to be paid from the Tourism Development Zone, in which incremental increases from state sales taxes collected from purchases in the zone are remitted back to Memphis from state government. That’s the same source of money being used to retrofit The Pyramid and which is producing about $100 million in Bass Pro improvements.

Here’s the thing: the TDZ funds can’t be used for anything else so it’s use them or lose them. We know from experience that when City of Memphis goes to Nashville and asks for some small amount of help, it regularly is shown the door. With this funding, money spent in Memphis stays in Memphis and it in effect it is producing new local sales tax money and hotel-motel funds.

We’ve asked a lot of hard questions about The Pyramid deal in the past five years, and we have been skeptical. However, every question has been answered with hard numbers, independent studies, and safeguards. There are cities across the U.S. taking huge risks, but Memphis’ risk is minimal and measured, and we moved into the plus column because of it.

I would take it one step further and say that in some ways, cities and the people in cities need to be comfortable with some forms of failure.

Often times the things that have made cities the greatest places don’t ever pencil out on paper. We might never see a *direct* ROI on some things.

To put it in terms that many people understand – look at some things a city needs to do as though they were the yard work around your house. There are several ways it can go. You can put in the hassle and sweat of doing it yourself, and a little expenditure on some basic yard tools and supplies. You can hire someone else to do it for quite a bit more money – but much easier for the “lazy” (or more likely people who are just out of time). Or you can not do it at all and let your place look like a rathole.

The only one that really pencils out on paper is pretty much the not doing it at all (or at a very minimum only doing the least possible to keep things from getting dangerous or causing damage).

Yard work will *never* pencil out. The investment in the yard will NEVER add enough value to the house to look good on paper. (It’s like adding accessories to a motorcycle – you might have $10,000 in chrome added on but the motorcycle will still only sell for $5000).

So why do yard work? Because we collectively don’t want to live in ratholes.

Indirectly of course, there is both a cost to not doing yard work and there is a gain to doing good yard work. And it’s not one to one. My yard alone will not impact the value of any house – but every yard in the neighborhood will. If all the yards are nice the neighborhood will be values higher eventually, or if they collectively all go bad – so will the values in the neighborhood.

Cities have this “problem” in almost everything they do. There may not be a direct ROI on something, but having a nice yard (or a motorcycle with all kinds of extra chrome) is nice.

Cities need nice stuff. Some times when looked at on an item per item basis, the stuff has no ROI. But if a city is full of nice stuff you get these benefits which are not directly attributable to a line item in a city council meeting:

1. People like you city and want to go there. Tourism dollars are great because they are dumped into your local economy from someone else’s job base. Every time someone comes to a city and likes it, they will tell other people, they will plan conferences or work trips to your city, etc etc… (the opposite is also true – if your city sucks, people will tell people and everyone will start to think your city sucks even if they have never been there).

2. People who are decision makers will chose your city. Sure tax abatements or under-the-table deals may help get a plant with 100 low paying jobs to build in your city. But that doesn’t really help all that much. But like item number one, if people like your city – ultimately some of those people will be decision makers. An Executive comes to your city for a conference, falls in love and ten years later moves the corporation to your city – wham, hundreds of mid and high paying jobs. Remember, executives and managers have to have nice places to live and recreate. Without those, headquarters will not want to be in your city.

3. People will have pride in their own community. It is kind of a chicken/egg problem. But if people think their own home town sucks they will do little to protect it. However, if you build a place that is wonderful more citizens will take an active part in protecting it.

None of those three things can be itemized or amortized in charts graphs or budgets.

Cities need sidewalks, bike lanes and bike paths, parks, museums, riverwalks, attractions, nice street lighting, quiet places, bustling places, all sorts of things. People need to be comfortable with saying “Our government is going to spend $100 million dollars over the next decade making nice stuff” and be OK with that.

You can’t put a dollar value on civic pride.

Based on my travels I recommend this: People like water and views. If you have water – develop it for the citizens so they can enjoy it. If you

can develop some sort of area where people (normal, not wealthy people) can see your city from the air – it gives people a great view of their home and builds great love for the community (if you have no natural elevation like mountains in the city – think Space Needle, Sears Tower, Empire State Building, Stratosphere, The Tower of The Americas, Canada National tower, etc etc etc)

VR: Beautifully said. Thanks.

The next big thing Memphis needs to do is establish a TDZ for the Graceland area. In Atlanta they use TADs to rebuild areas, it works the same way as TDZs, is it possible that Memphis can use a TDZ for areas such as Hickory Hill? It seems like cities that use TADs or TIFs (Tax Increment Financing)are successfully redeveloping depress areas.

City of Memphis might find it hard to establish a TDZ for Hickory Hill without a clear tourism engine there, but it certainly could establish a TIF or a BID there, and it seems like the timing for it is right now.

Thanks Smart City Memphis. Memphis needs to establish a TIF in Hickory Hill, ASAP. Memphis also need to establish a TIF for the Airport area to help build the Aerotropolis plan. A TDZ for Graceland and TIF for the Airport Area can help create another booming area in Memphis.

About one-fourth of the sales tax revenue increase in the TDZ is local sales tax money that will go to the project as well as the state sales tax funds. So I don’t see any new tax revenue being produced in the TDZ that will go to general government or school purposes. And to the extent that Bass Pro and other new developments down there draw retail spending from the rest of Memphis and Shelby County, Memphis city government and schools will lose local sales tax revenue. At the same time, I and other property taxpayers across Memphis will have to fund fire, police and other city services in the TDZ. This will be among the needs that may very well require another property tax increase in the future. I can accept all of this. I think that development of the downtown area is good for the overall city and I don’t mind paying higher city property taxes to support this. However, I would like for city officials to stand up and forthrightly tell me and the rest of the public all of these things. My problem with the elected officials is that they simply will not be forthright with the public.

Very nice article guys. Articles like these are why I love this site.

I applaud the city for building up its convention center area. I work for a company here in Memphis that attends a lot of business shows around the country. So far, I’ve had the opportunity to attend the convention centers in Boston and Orlando. Both are top notch facilities. Especially Orlando. Also, when you attend one of these events, you start to realize just how much money is being spent and poured into the local. I think what a lot folks don’t realize is that there is a ton of money being dropped in the evenings when these folks leave and head out for dinner and drinks. Folks really drop the hammer on the evenings after the day is over.

That being said, Memphis has chance here to really capitalize on walkability around the convention center. As nice as Orlando and Boston are, neither have the walkability that Memphis could have after this thing is complete. The city of Boston is walkable but the location of the convention center is not. It is separated from the rest of downtown. And Orlando, you have to ride the bus to get to the center.

That’s why I’m excited about this project. If it’s built like it’s supposed to, Memphis could see a very nice return IMO.

Did you guys see the study a few years ago that showed that cities don’t have to hire added police and fire for tourists because they don’t need those services. Other cities handle it under their current setup. I don’t see why we can’t either.

Thanks, mtown85, we appreciate it.

jcov40: The market and financial studies are extremely thorough and detailed and the quantify the new revenues to the hotel-motel tax and local sales tax, especially the portion going to schools.

40% of the spending at The Pyramid comes from new visitors to Memphis, so it’s new money injected into the economy here. So it’s not simply moving money from other retail stores to this one. I want to emphasize that the school portion is exempted from the tax collections.

Based on my information and watching the Bass Pro hearings on line, there’s been more information about this project produced and distributed than any we’ve ever seen. And the fact that the city now includes information about risks seems like progress to us.

My information through the years has been that all of he local sales tax increase in the TDZ, including the schools’ normal one-half share, goes to the TDZ fund. If I am wrong on this, I would like for somebody to show me some proof. Now at the state level, I believe that one-half cent of the seven-cent state rate is retained for the state education fund. Generally, I think about half of the state sales tax revenue goes to education so the one-half cents is really only a small part of what would normally go to state education funds from TDZ funds.

Overall, it seems to me that the downtown area is pretty much a “dead zone” as far as producing tax revenue for general government purposes, including city services in the area. I believe that general government services in the area are funded primarily by tax-paying residents in the rest of the city. If I am incorrect on this, I would like for someone to show me how I am wrong.

That’s not what the lawyers and financial analysts said in the presentations to Council, and even the percentage of the state sales tax allocated to schools was exempt. The state said what percentage this was and it’s calculated into the formula.

We know that we pay a special assessment fee that covers additional security and services so we sure feel like we’re paying for services, including through property taxes. And so much of what we deal with downtown isn’t the result of downtowners but because of tourists and residents enjoying downtown amenities. We’re o.k. with some of our special assessment and property taxes going to pay for that because we know that it’s the role of downtown.

Just because lawyers and financial analysts say something to the council doesn’t make it so. I still haven’t seen any evidence that I am incorrect on the local sales tax. I have gone back and read the law on it. I am not a lawyer but it seems to be written in pretty clear English. There is no exemption listed for the schools portion of the local sales tax.

And a letter from the state said it was so.

“…….. ‘disparate’ and diverse groups……..”

I heard “disparate” 5 times yesterday from 3 different talking heads including Rev Al Sharpton. Is this the new word of the month?

Put it up there with actually, my thought pattern, rigorous, and surreal.