| From Sustainable Cities: |

|

Mark Nickita, is an architect and planner Mark Nickita, principal of the city’s Archive Design Studio and a lifelong Detroit resident. In a very refreshing change from the mind-numbing negativity one usually hears about the city, Nickita is upbeat and hopeful. His point of view, emphasizing revitalization, is much closer to my own than much of what I read, which effectively takes the approach that the city has somehow been abandoned beyond redemption, leaving the only question how to manage its more-or-less permanent shrinkage.

But it’s not that simple.

There has indeed been a decline in part of the region. In 1970, 1,670,144 people lived within the city limits of Detroit. By 2010, that number had declined to 713,777, an astounding apparent loss of some 57 percent of the 1970 population. Recently, much has been made the 25 percent population decline over the last decade, from 2000 (951,270) to 2010.

But the extent to which Detroit is such a tragically “shrinking city” depends on your definition of “city.” The population of metropolitan Detroit – the jurisdictional inner city and its immediate suburbs – did decline from 1970 to 2010, but only from 4,490,902 to 4,296,250, a loss of only four percent. Big difference.

Do the math: what that means is that, while the inner city’s population was declining so drastically, its suburbs added some 761,000 people, growing at the handsome rate of 27 percent. (In the most recent decade of 2000-2010, the suburbs added some 91,000 people, or between two and three percent.) Patrick Cooper-McCann writes on his blog Rethink Detroit that, far from shrinking, the physical size of metro Detroit grew by 50 percent in those 40 years. As I’ve written before, neither the economy nor the environment pay attention to jurisdictional lines; neither should analysts.

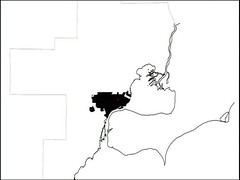

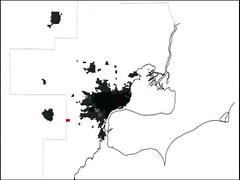

Look at the maps below. On the left, the physical size of metro Detroit around 1900; on the right, by 1950 the developed area had grown:

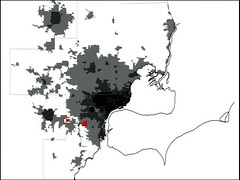

And by 2000, it had become immense:

Under current trends, it’s only going to get more expansive: As of 2004, the region’s planning agency was predicting that, over 30 years, the amount of developed land in metro Detroit is going to expand yet another 36 percent or more. “390,000 more acres bulldozed for progress. The development will continue to be mostly single-family housing, and will require more sewers, more stores and more schools,” wrote Sheryl James of the Detroit Free Press (published on the web site Urban Planet).

Shrinking city? Really? What this tells me is that an even bigger problem for Detroit than the decline of the rust-belt economy has been that the fringe of the region has been allowed, more than in most places, to expand, not shrink, and to suck the life and hope out of the inner city. So why aren’t the self-styled progressive responses to “the Detroit problem” addressing this critical aspect of the problem?

Maybe they are, but the only ones I hear and read are about “right-sizing” the inner city – demolishing vacant (and even some occupied) housing, letting vast areas revert to nature or farming, and so forth. Let sprawl, the cause of the problem, be someone else’s issue to address. But, in fact, the areas that are sprawling are where the “right-sizing” most needs to occur.

Whether or not there is any good in the current approach for Detroit as a community, it is impossible to see how it will be good for the region’s carbon emissions. Just as is the case in every other US metro area, households on the fringe emit far more CO2 than households in the center of the region, because their inhabitants walk less, drive longer distances, and drive more often. On the map above from the Center for Neighborhood Technology, households in the areas in red emit, on average, 8.6 metric tons or more of carbon dioxide per year from transportation; households in the pale yellow areas in the center emit 3.3 metric tons or less. Again, big difference.

The way to stem pollution is to address the unchecked expansion on the fringe and keep the center as urban as possible. In this troubled place even more than in others, Detroit needs a regional approach, not just demolitions in the center.

I’ve wondered about this. About whether the media reports of Detroit as a real-life “Escape from New York” were overblown hype, or an accurate report of what life is like for a Detroiter (Detroiteur?). They’ve still got teams in all four major North American sports leagues, so surely someone’s watching, right?

This reminds me of the media coverage of Memphis’s recent “flood of the century,” which (arguably) did more economic damage to Memphis than the flood itself. Article: http://onforb.es/k1pt8F

Detroit is psthetic. Memphis in many ways is not far behind

Anonymous: There is no data-driven argument that Memphis is not far behind Detroit. No data at all to support that theory which seems more race driven here than reality driven.

Detroit, nonetheless is, and has been pathetic for decades! anyone hald-blind can see and read about that.

I guess perhaps some might also think that Memphis and Detroit are constantly mentioned in the same breath.

Sorry to point out, but race IS a factor…like crime, health, education, and a ton of other variables.

I guess some also might not think that black-on-black crime itself is not a factor in dragging a city into the dumps.

I think most of the people already know about how social dynamic can, and does influence ‘city life’ and well-being….

Race matters….behavior matters more, no doubt.

Race and racial relations have factored greatly in the development of Memphis, and in its lack of development as well…that’s obvious to most anyone.

Anonymous: This blog is generally about making statements that are supported by factual evidence. Your statement may be supportable by such evidence, but it’s up to you to provide it. Make your case, please.

Surely you’re kidding ! I don’t find any requirement for any poster to ‘support by factual evidence’ any freely given opinion. Since when is issuing a statement of opinion reuqired by another poster to provide EVIDENCE.

Look, most forumms exist for providing opinion, not necessarily fact.

Duh, this is not a court of law, pal.

Get real…it’s the web, not a research academic effort for godsake !

“Make your case” ???????? how silly indeed. You must be watching too much television such as “Judge Judy” and “Dr. Phil”.

Memphis sometimes even surprises me with such third-grade logic and parochailism.

But, just as an aside, do you have any facts to offer that supports your ad nauseum opinions.

opinions don’t need your factual adjudication…imagine that ‘fact’

Of course, people are perfectly welcome to have opinions that are unsupported by fact. But if you’re actually hoping to convince anyone, as opposed to posting for the simple pleasure of hearing your own voice, then your opinions will be a lot more persuasive with some kind of factual support.

You don’t seem willing to provide such support. And that’s fine; you keep your cherished “opinion,” and I’ll keep thinking you’re a crackpot. At best.