To read entire commentary from Urban0phile, click here.

…I gradually became aware that many of the stops were at Sim-city like attractions – the kind you are allowed to build when your city gets to a certain size- such as the convention center, an arena, a baseball park, a football stadium, and a casino. Each of these must have taken hundreds of millions of dollars to build. I thought, “They’ve been spinning the roulette wheel, hoping to get the tourists and suburbanites back into the city”. But what had the city fathers done for the residents themselves? Later I was to walk through Campus Martius, a center city park that people take considerable pride in, but even in the middle of the day it was largely empty. On the last day of my trip I walked up Woodward Avenue, the grand street at the center of the city that used to be the main place where people shopped. The buildings on one side were largely empty. The buildings on much of the other side were simply gone, some torn down for underground parking garages that were to be the new base of new office buildings to be built by private developers. These office buildings didn’t materialize.

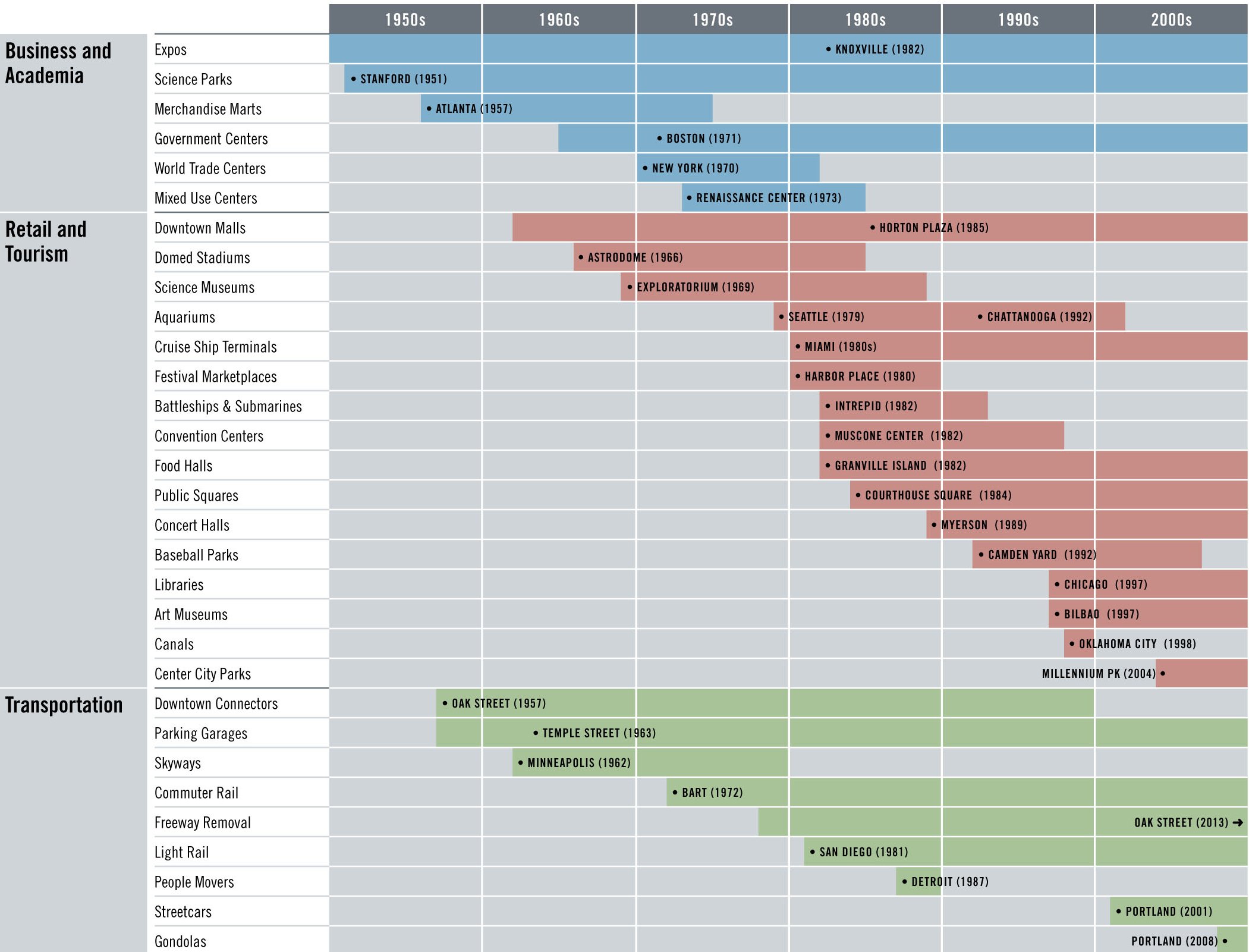

After this trip I began to compile a list of the “silver bullet” solutions, of redevelopment projects that city leaders have put in place in various places across the U.S. over the last sixty years like those I saw in Detroit, and that I present here. Early in my career I prepared marketing and feasibility studies for these things, so I knew there would be a number of different kinds, but I was still surprised at their number when I stopped counting. Like Baskin Robbins, there are 31 flavors on the list, and it would be easy to add to it.

Graphic by Carl Wohlt from an original chart and information by Rod Stevens/Spinnaker Strategies. Please do not re-use without attribution.

I have divided these into three kinds of projects: business, retail and tourism, and transportation. The bars show the decades they span, from the 1950s through the 2000s, with the earliest kinds of projects shown first. Expos, first on the list, actually started with the Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition in England in 1851, which later inspired Chicago’s “White City”, but my time frame here starts after WW II, when American cities began to consciously redevelop themselves in the face of suburban competition. For each kind of project I have also included an example and the year that example opened. The examples were not always the first built, but they inspired others to follow. For example, the Ontario Science Centre came before the Exploratorium as a modern, hands-on science center, but it was the Exploratorium that most of the other centers in the U.S. looked to as an example. San Diego’s Horton Plaza was not the first downtown mall, but it excited a lot of talk in the world of urban development.

Notice that the largest category is retail and tourism. If you really looked behind the rationale for most of these projects, you would find that most were in fact aimed at tourists or at suburban shoppers who had fled the city. The grand-daddy of all redevelopment projects is Ghirardelli Square, which remains vital to this day, although the upper floors have now gone condo for rich people who want to keep a place to stay in the city. Ghirardelli inspired the festival marketplaces of the 1980’s, many built by the Rouse Company, and many of which are now struggling. These later morphed into the food halls inspired by Granville Island in Vancouver and the Pike Place Market in Seattle, and, more recently, the market halls or sheds for farmers markets that have recently begun to show up. Notice the trend here for an ever-more-local clientele. Partly this is due to retail trends. When Ghirardelli first opened, it was filled with unusual boutiques selling clothing and glasses not found in the malls. Today you can buy these things at suburban “town centers”, where chains like Crate and Barrel keep a good selection of wine glasses and linens.

There is almost a flavor-of-the-month approach for transportation as well, which really started with the downtown connector freeways aimed at whisking shoppers to ailing main streets. More and more cities are now tearing out these freeways and converting the space to parkland. What’s more interesting is the evolution in rail, from heavy systems like BART and the DC Metro, to light rail in places like San Diego, to the current passion for street cars. Transportation is becoming lighter than air, and now this is even an urban gondola in Portland, with Vancouver planning a second on Burnaby Mountain. Years ago Disneyland had one of these, for frenetic visitors eager to punch all of their E tickets.

Notice how few kinds of business-related projects there have been. Science parks, which started with Stanford and the Research Triangle, have mostly been in the suburbs, but a few are in the city, such as Yale’s Science Park, and more are on the drawing boards. Carnegie Mellon’s Collaborative Innovation Center may be the best example of integrating academia, industry and the city, for here private sector tenants come together on a campus in the middle of a very urban city.

Notice just how briefly projects like Renaissance Center were popular. John Portman, an Atlanta architect, designed the most prominent of these, including not only Renaissance Center but the Hyatt Regency/ Embarcadero complex in San Francisco (which is connected with sky bridges), Peachtree Center in Atlanta, and the Bonaventure Hotel in downtown L.A. At the time these were the wonder of their cities, and tourists came in to gaze upward at the atriums and light-bedecked elevators that moved through these. They almost all included office buildings, hotels, and mini-shopping malls, and almost never housing. Many of these were introverted, arrived at by car in special drop-off lanes, with the pedestrian entrances being hard to find. Few or no lobby windows faced out onto the street. At Embarcadero Center in San Francisco, the main level of pedestrian activity is one floor above the street. and for about 20 years it had a thriving trade of office workers from nearby buildings eating and shopping there at noon. Now most of that lunchtime activity is out walking along the Bay, on the true Embarcadero, or eating in the Ferry Building next to it.

And then there are the truly wacky projects, which may or may not work in their own right. Projects like the automated people movers in Detroit, Miami, and Morgantown, West Virginia. The canal in Oklahoma City’s Bricktown “entertainment” district. And the submarines and battleships, like such as a submarine in the prairie land of Muscogee, Oklahoma and the dreadnaught Olympia at Penn’s Landing in Philadelphia. The Olympia ship may be headed to the scrap heap, for lack of support and visitation and Penn’s Landing has struggled because of its isolation. Fish don’t shop.

Why is it that these projects work in one place and not in others? And why is that Portland has pioneered so many of these projects? I believe the answers are related, and having grown up in Portland, with a family that was involved in creating some of these solutions, I can offer some insight.

Aaron Renn uses the term “silver bullet”, and that is exactly why many cities copy other cities’ solutions: they hope these will magically solve their problems. But as Aaron points out, these other cities frequently fail to adequately define what problem they are trying to solve, and what their priorities are. The approach that works well in one city for one set of challenges will not work well for a different set.

But why has Portland been so successful? I believe there are three reasons: 1) crises and political turnover that opened the community up to questioning and new leadership; 2) a growing facility with problem definition and problem solving; and 3) the attraction of “outsiders” who joined the community and brought fresh new approaches and energy.

Yeah!

Great post.