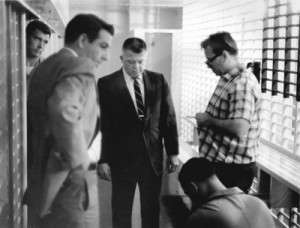

The release of photographs of James Earl Ray’s booking into Shelby County Jail reminded us that someone needs to record the oral history of Bill Morris, sheriff at the time of the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and later to be Shelby County Mayor.

Mr. Morris was the Josh Pastner of law enforcement when he was elected as the youngest sheriff in the history of Shelby County. He was 32 years old and none of the political old-timbers expected him to beat a much older sheriff connected to the fabled Crump machine.

His political springboard was the Memphis Jaycees, a group of impatient young businessmen who decided that it was time for fresh leadership in local politics. The group was the seedbed for several of the now familiar names in our government history, but back then, they got much the same treatment by the established political structure that groups like New Path get today: lip service and a pat on the head and told to wait their turn.

Historic Times

Mr. Morris had other plans, and running on a platform of ushering in a new day in the crony-larded, white sheriff’s department, he defied prognosticators and took office in 1964 as the Civil Rights Act was passed and in the wake of the Klan killings of three civil rights workers in his home state of Mississippi.

It was a turbulent time in the South and pandering for white votes was common, and yet, the new sheriff managed to keep his balance and his significant African-American support. His African-American base remained intact and was instrumental to his later election as Shelby County mayor in 1978, an office he held until 1994 with only nominal opposition at election time.

Four years after he took office as sheriff, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Sheriff Morris got one of the first calls about the assassination, and while driving on Riverside Drive, he flagged down Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb to tell him that Dr. King had been shot.

Fighting for Memphis’ Reputation

Historical footnote: the first police dispatches called for patrol cars to be on the look-out for a car chase with a possible suspect that was speeding out of Memphis. One car’s description matched the sheriff’s car and the other matched the car owned by Memphis black militants, The Invaders, who had that afternoon been kicked out of the Lorraine Motel after the objections of King insiders. Conspiracy buffs see it as the first of several things intended to throw the blame for the shooting to the militants, who had been infiltrated by an FBI undercover agent and was also a subject for the Ernest Withers reports.

Two months and four days later, James Earl Ray was arrested in London and quickly extradited to Memphis. That’s where the Morris story really gets interesting.

FBI officials viewed Memphis as a backwater river town as surely as Time magazine did in its infamous description of our city. Sheriff Morris was young, untested, a Southerner, and Memphis was rapidly being smeared as a hotbed of white supremacy, all of which gave the FBI serious concerns about Memphis’ ability to keep Ray safe; however, it was not long before the sheriff and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover were on each other’s daily call lists.

The Arrival

Sheriff Morris’ office was on the second floor of the southeast corner of the old Shelby County Criminal Courts and Jail building in downtown Memphis (now the Shelby County Archives). The front of the building faced Washington Avenue, and the entrance to the jail was on the back of the building, crowded by the newer Shelby County Administration Building.

Access to the jail was primitive by today’s standards. Deputies drove their squad cars to the back of the jail building and walked the defendant to the back door, where they were buzzed in and the processing of the accused began.

Before James Earl Ray’s airplane ever arrived, the world’s media had encamped at the jail door, surrounding anyone who stepped from a county squad car. To prepare for the most famous murderer in the jail’s history, Mr. Morris had arranged for a complete medical physical – with photographs – of Ray so there could be no allegations of brutality.

Invisible

Because the jail was not air conditioned, the cell block where Ray ended up – on the second floor of the northwest corner of the building – regularly had the windows opened to ventilate the cells. Passersby could occasionally even see inmates who sometimes stood on the bars of their cells to get higher for better breezes (and to sometimes yell their carnal desires at woman walking by).

To prevent anybody from being able to see James Earl Ray, particularly through a rifle scope, Sheriff Morris had steel plates placed over the windows and there were no other prisoners in the entire cellblock except for the world’s most famous murderer.

Faced with the gauntlet of reporters and photographers, the sheriff concocted an ingenious scheme at one point. He dressed Ray as a sheriff’s deputy and walked him directly through the journalistic melee without a single reporter noticing. In an epic tale, it is one of our favorite Morris anecdotes, but it is just one of many that someone should record for the ultimate insider’s view of a chapter of Memphis and U.S. history.

The Story Continues

Based on his handling of Ray, Mr. Morris was asked to advise on the security of Sirhan Sirhan following his murder of Senator Robert Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He left the sheriff’s office in 1970 and six years later, he was elected Shelby County mayor after putting together an unusual coalition of African-Americans and young Republicans.

As the longest serving mayor of county government (there is now two-term limit), Mr. Morris was mindful in his 16 years in the office that he was shaping the powers of the newly created chief executive’s job, and because of it, he drew a strong line in the sand when it came to legislative encroachment and to demanding equal standing with the Memphis mayor. Through sheer power of personality, he elbowed his way into the public spotlight and into countless events with the city mayor, leaving a legacy of equality that is unusual in most cities and that continues today for the county mayor.

But what people close to him remember most is that while open to new ideas and provocative policies, he never asked if they would lose votes or gain votes. That alone is worthy of an oral history of his public service.

I’ve heard so many interesting stories about Bill Morris (no familial relation) over the years. I’d like to get him on the record about this one: After Ray’s guilty plea, Sheriff Morris safely transferred custody of Ray to state prison officials, but not the typical way. The prison officials were scheduled to pick up Ray at the jail at an appointed time, which the press knew. Instead of waiting for them, Sheriff Morris surreptitiously left the jail with Ray hours earlier, but not in a government vehicle. Sheriff Morris enlisted the help of an old Jaycee friend who was an early adopter of technology and had a primitive car phone. His friend drove Sheriff Morris, a deputy and Ray around Memphis killing time until they contacted the prison officials via the car phone to alert them that they would meet them at a particular spot on the highway, where the transfer was made without any fanfare. While killing time driving around Memphis, Sheriff Morris’s friend mentioned to Ray that his picture was in the latest edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Ray was quite interested to see for himself, and they drove to the friend’s house to retrieve the applicable volume to show Ray, who seemed perversely delighted at his infamy.