Sometimes, it seems that Memphis simply runs the risk of falling off the grid in the future.

We admit to these thoughts when we look at maps showing critical plans for the new economy infrastructure and the platform from which cities like ours will compete in the coming decades.

There’s the map of the high speed rail corridors.

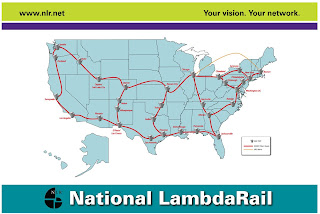

There’s the map of LambdaRail optical network infrastructure.

There’s the map of Internet2 hybrid optical and packet network.

There’s the map of the U.S. megalopolises, the super-regions that will inevitably become the economic units for the U.S. in the global economy.

Sewing Up Old Jobs

As a result, there’s the uneasy feeling that we are so busy in Memphis hanging on to the threads of the past economy that we aren’t paying attention to the fabric of the coming economy.

Because Memphis operates from an attitude of scarcity, which begets the “if you’re winning, I must be losing” approach, we tenaciously hang on to the low-wage, low-skill jobs that are too much at the center of our economic development strategies.

We continue to sell our region for its cheapness. Unfortunately, we aren’t aware of a city that is succeeding or positioning itself for the future on the basis of cheapness. The currency of success is quality, and most often, it’s the high-cost cities that have expanding economies.

Here’s the thing: smart people are congregating with smart people, and the trend is accelerating. Today, 16 cities are attracting most 25-34 year-olds, and it probably unnecessary to mention that Memphis isn’t among them. In the first seven years of this decade, our city’s percentage of this age group fell from 25.6% to 21.8%, or a loss of just over 5 people a week for seven years.

Cheap’s Really Expensive

In other words, Memphis isn’t on the positive side of today’s trends, and as they step up their speed, we’re not just running in place. We’re losing ground. Business as usual will not change our relative position, so let us say it again: it is hard to find any data that shows that cheap is a successful strategy.

The problem is that there’s really not much market for cheap, and there’s absolutely not one in a knowledge economy characterized by and dependent on innovation and creativity. That’s why we have to be more intentional about our economic growth strategies and why we need to be creating a plan to compete 10-20 years from now.

It would be encouraging if our economic development officials could show as much passion about planning for the future as they do hanging on the tax freezes for jobs in the old economy. We have to think differently, because the Memphis region is heavily reliant on energy-dependent industries and we are are essentially betting all of our chips on their future.

Even if they find ways to become more sustainable and energy efficient, it is unlikely that they will ever be the high-value jobs that we need, meaning that our region will continue to be in the bottom rungs in income and college attainment.

Getting It Right

It’s become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Our economic development officials say that we have to give tax freezes to low-wage companies because we have low-skill workers. More and more of these jobs increase their impact on our job market and perpetuate the national reputation of Memphis as a city with a poorly trained and educated workforce.

Maybe we break out of this race to the bottom by sending the message that we are setting bolder and more ambitious goals for ourselves by aggressively working to put our city on the map for the major projects of an economy built on connectivity.

It’s all about connecting our people to the regional economy and our regional economy to the global economy. That’s why the LambdaRail and Internet 2 are so important. Now we are outposts for the networks, and it’s almost as if the plans leave a hole in the middle of the country, leaving us in the hinterlands between Nashville and Tulsa. The networks are the backbones for innovation and research.

Then, there’s the high-speed rail corridors mapped by the U.S. Department of Transportation — the line from San Antonio to Dallas to Little Rock, one from Houston to New Orleans to Atlanta and another from St. Paul to Chicago to St. Louis to Kansas City.

Railing For A Better City

In other words, the closest one to Memphis is about 120 miles away. The Obama stimulus funding bill provides $8 billion for high-speed and intercity rail projects, and support will be sustained with $5 billion over five years to states. Of course, that’s only a start, since the plans in California alone cost $40 billion, but already, cities are pitching high-speed rail as essential to economic growth, particularly if it connects with a multi-modal center connecting to airports, ports and public transit.

It makes Memphis, Shelby County and Tennessee governments’ continued chase of I-269 pathetically misguided, because other cities are getting it right, campaigning for their place on the map of high-speed rail.

All of this is taking place in the age of the megapolitans, super-regions strung together by economies, commuting patterns, culture and demographic trends, giving birth to what are becoming the super-novas of the global economy.

More than two-thirds of the country’s population already live in 10 megapolitans, which are growing at a faster rate than the U.S. as a whole, according to Robert Lang, the Virginia Tech University professor who’s become the nation’s expert on this statistical phenomenon. He predicts that the population of the megapolitans will grow by 85 million people and see $33 trillion in construction spending in the next 35 years.

Wrong Place At The Wrong Time

The problem for Memphis is that when the age of megapolitan areas dawns, we’ll be in its backwater, no closer than about 200 miles to the nearest one – the Piedmont megapolitan area, which embraces 19 million people in an area that stretches from Charlotte, Raleigh, Atlanta and Birmingham. Its western edge teases the Nashville metro.

The largest of the megapolitan areas is the gigantic Northeast, stretching from New England to Northern Virginia and holding 50 million people and a $3 trillion economy. The Pittsburgh, Detroit and Chicago corridor holds 40 million people in the Midwest; Southland embraces Southern California and Las Vegas with its 22 million people; the I-35 megapolitan area runs from San Antonio, Dallas and Kansas City with 15 million people; and the Peninsula is essentially all of Florida south of the mainland and holds 14 million people.

It’s unlikely that Memphis will become part of a super-region. We’re just too far off the growth corridors, and it seems unlikely that I-69 – which on most days feels more like a real estate scheme than a transportation plan – can produce the kind of growth that could attach Memphis to the Midwest megapolitan, and it seems even more unlikely that the Piedmont super-region will ever ooze this far west.

However, that doesn’t mean that we should not be exploring ways to create connections to the megapolitan areas that will be the centers for economic activity in the future. If Memphis continues to be willing to continue to sell itself at a discount, our city will continue to pick up the crumbs from the knowledge economy table. More to the point, we need to be creating scenarios in which we get our city on to the grid that will spell success in the future.

It may take a citizen revolt to make it happen, to make sure we’ve got the most progressive agenda, to make sure we’re having the right conversations and to increase the intellectual capital brought to issues and to spark new thinking. Best of all, the seeds of that revolt seem to be bubbling beneath the radar and can it has the power to change everything.