For seven years, I walked out to my driveway each morning with a knot in the pit of my stomach.

The morning bout of angst may have been bad for me, but it was good for Memphis.

I was a reporter for the Memphis Press-Scimitar and the competition between the afternoon newspaper and The Commercial Appeal was fierce. All of us opened our competitors’ papers with trepidation. Often, we didn’t even get the chance to open the newspaper, because the metro editor was already on the phone yelling about some the story we missed. It was an age when “scoop” really meant something; when we called ourselves reporters, not journalists; and when colorful characters filled the newsrooms.

There was the reporter who called in drunk from Dyersburg to report that no protests were taking place there. The only problem was that he was supposed to be in Forrest City. There was the reporter in the cop shop who got so mad at an editor that he threw his phone out the window into Second Street. There was the old-timer who regularly called in an insert to a story that was longer than his original copy. There was the guy who slept for months and months on a table at the Press Club. There was the reporter ordered to investigate the repairs of personal cars in the county auto shop but first had to get his car out. There was the shoving match between reporters from the CA and the Press-Scimitar in City Hall about who had broken a story first.

Bad Day At 495

Conversely, there was the reporter followed by the FBI because she was “too close” to civil rights workers. There was the series of articles about Memphis’ most powerful people that created a new understanding of how Memphis worked. There were daily stories that regularly shone light into backrooms, some based on purloined papers from the grand jury garbage and others from hiding in the Courthouse law library to overhear judicial ethics hearings. There was coverage that brought to live the panoply of people who made Memphis work, made it fail, and made it endlessly fascinating.

It was the post-Watergate era, and J-schools across the U.S. were jammed with young people looking to meet Deep Throat in shadowy garages to bring down the president. Back then, it seems that America was on the verge of a journalistic golden age, an era when the Fourth Estate would be the leveling force that would make democracy work.

Perhaps, in hindsight, we should have all known it could not last. It was just too good and too much fun, but then again, we also thought that we lived in a country of readers who admired the nobility of our profession. Surely, if there was anything that had special value to Americans, it was their newspapers. And yet, slowly, the world changed. People shifted to television news until today, 88% of people in Shelby County get their local news from television (which in truth has less and less news), compared to only 41% for The Commercial Appeal.

All of these memories come bubbling to the surface after hearing about “Black Wednesday” at our daily newspaper, as even more reporters were cut from the payroll. It’s all feels so much like a race to the bottom by an industry trapped in an Internet world with an offset press mind. It’s also strangely reminiscent of the grasping at straws behavior that typified the Press-Scimitar’s slow decline before it sank out of existence.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

There was the added irony that the firing of reporters came at the same time that the CA’s website proclaimed: “Poll finds some Tennesseans happier than others.” There was no question that this was the case in The Commercial Appeal newsroom, and perhaps the uninspired headline writing reflected the pall that hung over 495 Union.

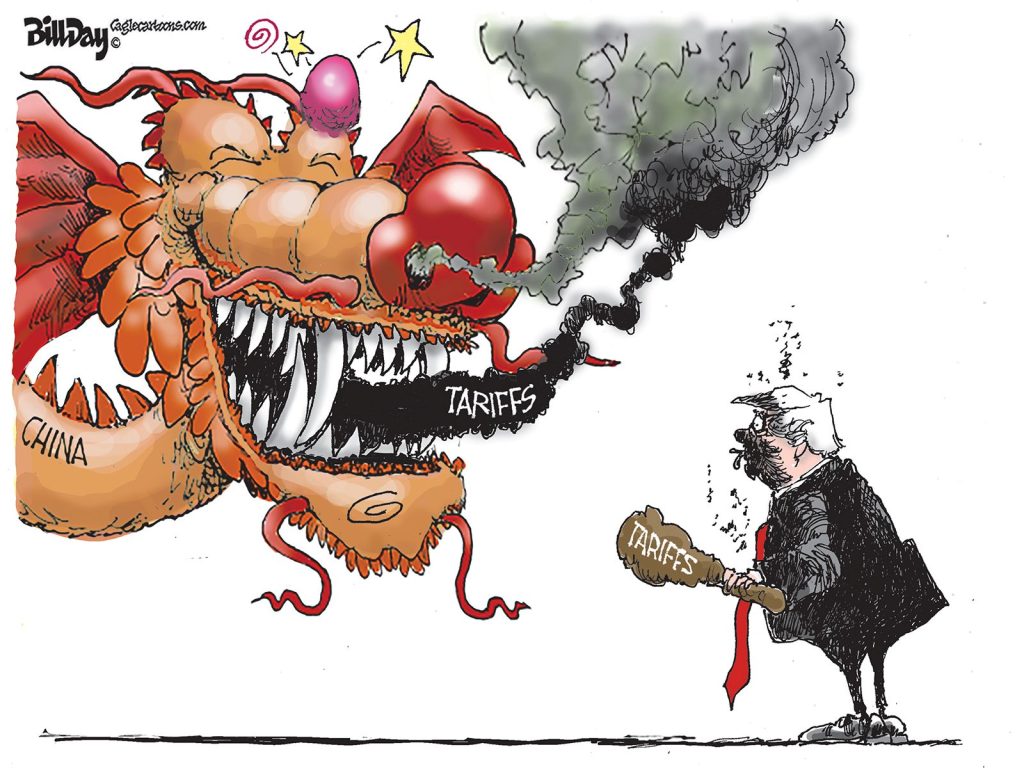

It seemed that in a final act of surrender, the newspaper slashed even more institutional memory with the layoff of the venerable Jimmie Covington, who has forgotten more about Memphis than the rest of the staff knows, and editorial cartoonist Bill Day, whose exit brings to a close the long tradition (rewarded with a Pulitzer Prize) of locally produced cartoons. One insider said that perhaps the CA will rely more on free content from “new Marilyn Loeffels and their blazing insights.” (The joke in the newsroom: Marilyn Loeffel’s column is free and the paper is still overpaying.) Meanwhile, another person said that if you want to see the reason for the newspaper’s decline, it can be seen in the editor’s column every Sunday. “Besides finding out who he met at a party this week, it demonstrates the absolute lack of understanding about what makes Memphis tick. It’s a weekly advertisement of how clueless management is.”

It may have been bitterness talking but seemed to reflect the general lack of confidence in the paper’s management. After all, The Commercial Appeal is certainly not alone in its crisis mode, a condition deepened by things like its suburban strategy – which dotted the landscape with offices but did nothing to attract subscribers (and in fact, might have resulted in a decline inside the loop). Circulation of the paper continued to slide until it fell below the magical 100,000. Advertising revenues fell off a cliff (across the U.S., they are down 25% from three years ago). No longer did the CA’s big story of the day dominate the conversation around the water cooler. There was no turning back.

Then the recession hit, and the industry was sent to the mat. What looked like a slow death for a number of papers was made quicker. A few died and several seem headed for the morgue. Some major newspapers have become on-line only or and some have begun to experiment with publishing a few days a week.

Part Of The City Infrastructure

A couple of years ago, St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay, who normally used his blog to spotlight problems in this city and to occasionally complain about media bias, wrote: “The paper’s (Post-Dispatch) current struggling fiscal health and demoralized voice are drags on our own civic renaissance.” He’s right, but the fact that city mayors recognize the importance of their newspapers says volumes about the impact of smaller reporting staffs and fewer pages.

Before the Press-Scimitar called it quits on Halloween, 1983, there were nine reporters covering government and courts in downtown Memphis. Now there are three. Because of the aggressive competition between the newspapers, and more importantly, between the reporters themselves, there was regular behind-the-scenes coverage back then of the wheeling and dealing in government, there were the outtakes and anecdotes, there were stories connecting the dots and there was the in-depth articles that too rarely appear today.

“No one connects the dots, but it’s worse than that,” one former Commercial Appeal reporter said. “Now, no one even sees the dots. Most people who ‘got’ it are gone.” And despite watchdogs and on our side reporters, there’s just no way television news will ever fill this void. The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism has reported that a typical metro newspaper has 70 stories a day, and when sports and style sections are added, it’s more like 100. Meanwhile, a half hour of television news has 10-12 stories (typically with more about crime, fires, traffic tie-ups and weather).

Some people think that blogs can fill the vacuum, but they can’t. Some think newspapers will reinvent themselves into a digital form, but there’s no reason to feel optimistic about it. It’s just too hard for an industry defined by its legacy systems to adjust to the demands of today’s consumers. They want to individualize their own experiences and customize their own communications networks. Here, we receive more than a dozen newspapers a day, we receive a summary report of what the major papers are headlining, we aggregate stories about issues we’re tracking and set up searches for things we are interested in.

Six Bits

It creates a daunting challenge for newspapers to reinvent themselves in such a world. The trend in business, the arts and cities is that it’s the middle getting squeezed out. The large entities are succeeding because of their size. The small ones are finding niches. It’s the ones in the middle that are biting the dust. It’s a trend that doesn’t bode well for most big city newspapers, including The Commercial Appeal.

That’s how far the industry has come since the Watergate journalistic aura when predictions were that newspapers would leave the ambulance-chasing to TV and offer the kind of serious, literary journalism that the public would reward. That dream continues to walk out the door with the layoffs of newspaper veterans this week.

Standing in a Tiger Mart to pay my bill, the man in front of me lays down 50 cents for the newspaper, but the clerk tells him that it now costs 75 cents. “I just wanted to support them since papers are in trouble everywhere. I’ve been reading it online because I didn’t think it was worth 50 cents any more,” he said. “Never mind.” It was telling: a quarter was just more than the perceived value.

Molly Ivins said a short time before she died that newspapers’ answer to their problems is to make its “product smaller and less helpful and less interesting.” Perhaps that partially explains why the average age of a newspaper reader is 55 years old and rising and that only 19 percent of 18-34 year-olds look at a daily paper.

It Is Called The “News” Business For A Reason

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein shared her opinion: “People are becoming better educated, more sophisticated and more global, not less. The days are long gone when daily newspapers could satisfy readers – particularly the younger and more affluent readers that advertisers crave – by hiring inexperienced young reporters to write desultory stories about city council and planning board meetings or by filling much of the news hole with bowling scores, school lunch menus and bad photographs of high schools sporting events.

“News executives will often try to justify dumbing down their product, or making it more parochial, by explaining that local coverage is their unique competitive advantage and that readers who want more can always get it somewhere else these days, often for free online. I’m aware of no evidence that time-stressed readers would not value having a single, convenient and trusted source for most of their news. It hardly seems like a winning strategy to drive customers to other news sources when, with a little imagination and a modest investment, newspapers and their websites can acquire most of what readers want in the way of national and international news and features from quality news organizations eager to explain their reach.

“If you ask me, the challenge facing our industry is not that readers have lost faith in their newspapers, but that newspapers have lost faith in their readers.”

We hope he’s right, but we think that it’s time for both the left and the right to declare a truce in their wars against newspapers and stand up for the importance of newspapers in the history of this nation. Both ideological sides have benefited from the rhetorical wars based on the premise that journalists aren’t objective and fair, and now, less than 20 percent of people say they believe all or most of reporting. (Of course, the Judith Millers and Jayson Blairs of the world didn’t help any.)

But, first, the newspaper business needs to stabilize and acknowledge that its business model just doesn’t work anymore. Maybe MinnPost.com is a harbinger of the future as reporters join together to put out online newspapers. Maybe it’s the nonprofit model that’s gaining traction (although it seems to presuppose that the managers of a nonprofit newspaper will act nobly and impartially). It does seem, however, that if local business leaders were willing to pay several hundred millions of dollars for a dying professional basketball franchise, they might be willing to do the same for a dying newspaper franchise. It’s easy for us to figure out which is more important to our city’s success.

No Profits, Nonprofit

After all, while readership of newspapers has dropped into the 40 percentile and the average operating profit margin has dropped from 22 to 11.5 percent, that’s still has the potential to be a respectable business within the right business model. And that business model might more logically be a nonprofit one.

In the end, it’s our belief – dream? – that newspapers can still accomplish the goals set out by Walter Lippman so many decades ago. He said the average American is like a deaf spectator in the back row at a sports event. “He does not know what is happening, why it is happening, what ought to happen,” and “he lives in a world which he cannot see, does not understand and is unable to direct.” Explaining that world has uniquely been the responsibility of newspapers for 300 years, and it’s difficult now to see anything that can take its place.

The days when owning a newspaper was a permit to print money are long gone, and those who greet the industry’s travails with a shrug should think again. With the decline of newspapers will also come the decline of government accountability. Already, we are seeing the anti-media frenzy of the current Tennessee Legislature – apparently intent on staking a solid claim to being the most dismal group assembled in Nashville in recent history – playing out in the votes to block public records about gun permits from being published and recent attempts to weaken the open meetings laws.

We may have entered the era of what is loosely and oxymoronically called “citizen journalism,” and while we have blogs and commentaries at every turn from every one (including us), they also have no professional standards and transparency. More to the point, they will never have the impact of newspapers in getting the attention of corrupting influences in government and shining a powerful spotlight into the dark corners of political deal-making.

Democracy is stronger because of the Fourth Estate, and it seems that the future of The Commercial Appeal and other metro newspapers will only get more difficult.

We wish we knew the answer. We do know that we’re not reading The Commercial Appeal online tomorrow. We’re buying one.