New market tax credits, a little-known development tool for low-income areas, is making a high profile appearance in Memphis as part of the Bass Pro Shop financing package at The Pyramid.

That revelation was made to the Memphis City Council this week, although financial details of the package are yet to be revealed. However, it was announced that rent based on sales would be a minimum of $1 million a year.

It is a political bonus for elected officials to have the chance to announce that rent is being paid by Bass Pro Shop, and while the final computation of rental rates in the contract may make the federal tax code look simple, if $1 million is paid to local government each year by Bass Pro Shop, that amount would cover around half of the annual debt service still being paid by Memphis and Shelby County Governments on the cost of the signature building.

As for the new market tax credits themselves, they were created by Congress in 2000 as an incentive to make projects in low-income areas more attractive to private investors. Applicants vie for the credits in a highly competitive process.

In the first three rounds of allocations of the tax credits, which began in 2003, the demand for then has oustripped supply by 10 to 1. While the incentives can be used for business development, the majority are used for commercial real estate because of the way the program was structured in the “Community Renewal Tax Relief Act of 2000.”

Across the U.S., the credits have been used for the rebuilding of shuttered manufacturing companies, new business incubators, public markets, mixed use arts districts, charter schools and a community center. The credits can be used for virtually any business, with the exception of liquor stores, golf courses, country clubs, massage parlors, hot tub and suntan companies, racetracks and gambling facilities. In several cities, it has been the financial foundation on which downtown redevelopment plans were built.

The credits can only be used in low-income communities, which are defined as census tracts with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent or with median income not exceeding the greater of 80 percent of area median or statewide median income and, for a non-metro census tract, 80 percent of statewide median income.

Got it?

With the tax credits, investors pay lower taxes and the savings are passed along to the community through lower rent per square foot. Total disbursements so far have been $8 billion. The firms or investors who receive the market tax credits have five years to use them to attract private investment, or they are withdrawn and shifted somewhere else.

The New Market Tax Credit law has developed a cottage industry of advocacy groups and banks lobbying for its reauthorization in 2007, and since the program was expanded to help with the rebuilding of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast following Hurricanes Rita and Katrina, prospects are good for renewal.

According to the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, while inner city consumers represent $100 billion in buying power, unmet demand exceeds 25 percent in many inner city neighborhoods. Previously, the research of University of Memphis has shown that these neighborhoods are underserved with retail and can support more and varied businesses.

Ironically, when The Pyramid was opened, it was supposed to spark significant investment in The Pinch District and to create a lively district known for its restaurants, mixed uses and retail. In truth, The Pyramid did just the opposite, leading to the demolition of a number of buildings simply to make way for a more profitable revenue source — parking lots.

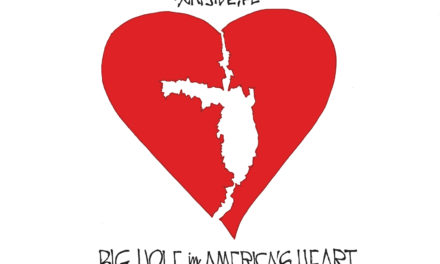

When the legislation creating the credits was passed, President Clinton said it was to expand economic opportunity to distressed communities. The area around The Pyramid is now the poster child for such distress, and hopefully, the introduction of New Market Tax Credits in such a highly visible way will encourage their use in inner city neighborhoods in desperate need of an infusion of capital for economic development.