This post represents the third (Part 1 and Part 2) and final tour of the Memphis parkway system.

By this time, you have toured South Parkway from MLK-Riverside Park to East Parkway, twisting and turning several times around its famous “jogs.” Once on East Parkway, you experienced an equally stimulating drive negotiating around the ever expanding and contracting East Parkway median. Now, you’ve reached what is one of Memphis’ more complicated intersections: East Parkway/North Parkway/Trezevant/Summer. Take a left and head downtown via North Parkway. Part of the confusion of this intersection is due to the history of these streets: just as East Parkway was aligned along the old route of Trezevant, North Parkway was laid out along what had been Summer Avenue, but the parkway designations were only applied to the sections of the roadway that had been given medians, so Trezevant north of this intersection remained Trezevant, and Summer east of here remained Summer.

The first thing you will likely notice driving along North Parkway is its relative straightness. The road has no twists and turns and no drastic median changes like its southern and eastern brethren, for as far as the eye can see. To your right is one of Memphis’ classic 1920s subdivisions, Hein Park.

Hein Park, which is now on the National Register of Historic Places, was laid out in 1925 by William A. Hein and features the same curvilinear street pattern and rural cross-sections (no curbs, gutters or sidewalks) as its sisters out east that were developed at about the same time, Hedgemoor and Red Acres. Hein Park has maintained its position among Memphis’ nicer neighborhoods over the decades thanks in large part to its close proximity to Rhodes College, which is the next landmark along North Parkway.

Rhodes College, known as Southwestern at Memphis until 1984, relocated to this site from Clarksville, Tennessee, in 1924. The most impressive architectural feature of the campus is its adherence to Henry C. Hibbs’ master plan for the campus and its replication of the original Gothic Revival buildings he designed. The president of the school at the time of the move to Memphis, Dr. Charles Diehl, bought an old stone quarry in Bald Knob, Arkansas, to ensure the consistency of the buildings. If you have time to walk around campus, you will find it hard to tell which buildings date from the 20s, 50s, 70s or 2000s.

The first traffic signal you will reach on North Parkway is University Street, which was named for the abutting Southwestern University. Note that University is one of the few streets of its vintage, besides the parkways, that features a median down the middle. Once past University, you will come across the first of two 1960s residential towers along North Parkway, Parkway House.

Parkway House, now a condominium building, was one of the first residential buildings in the city to style itself as a luxury apartment building. Two buildings constructed in Memphis in the 1920s were attempts at luxury apartment buildings: 1) the Forrest Park Apartments (now razed) near Forrest Park were planned to be a tenant-owned cooperative building with large units of 3 and 4 bedrooms, but the Depression struck and the building became an apartment hotel, and 2) the Parkview at Overton Park (now a retirement community), which was really more of a hotel than a true apartment building. Luxury apartments planned for Union and East Parkway in the 1920s (see my past post) were never constructed. Kimbrough Towers, at Union and Kimbrough, was arguably a luxury apartment building due to its 2 bedroom units, but was not marketed as such (it was completed in the 30s, a decade without too many “luxuries”). Memphis really had to wait until the 1960s for a true luxury apartment house that was marketed that way. The success of Parkway House set off a chain reaction in Memphis, as many more apartment towers would be built in the late 60s and 70s, especially adjacent to the Memphis and Chickasaw Country Clubs.

Immediately past Parkway House is the former headquarters of the National Cotton Council of America.

Having been at this location since 1955, the Cotton Council decided to move out to Goodlett Farms in suburban Memphis in 2008. Plans for a mid-rise apartment building to replace the old Cotton Council building have apparently been abandoned with the current crisis in the housing and construction loan market. Immediately past the old Cotton Council is one of Memphis’ most celebrated schools, Snowden. Constructed in 1909, with additions in 1924, 1939 and 1979, Snowden features faux columns on its entrances along the parkway.

The traffic signal at Snowden School is McLean Blvd. Overton Park has been on the left side of North Parkway for your entire journey up to this point, so once you pass McLean, you will be able to enjoy buildings on both sides of the street. The blocks west of McLean are largely single-family in nature. From bungalows to colonial to Spanish revival, some of the best houses from the 1910s and 20s in the city dot this stretch of North Parkway. The home at the southwest corner of Parkway and Evergreen even has a name (see below).

A few blocks past the traffic signal at Evergreen, the second apartment tower rises on your right. Formerly known as Woodmont Towers, the building is now called the Glenmary and serves as a retirement community. Never quite as architecturally stimulating as the Parkway House, the Glenmary was recently repainted in green tones to give it a little flair. Across the street, on your left, is Stonewall, the lone street in the very linear Stonewall Place Subdivision. Laid out by Robert Brinkley Snowden in 1909 on the heels of his success in Annesdale Park and Annesdale-Snowden, Stonewall Place featured one of the widest residential streets in the city at the time (see below).

Just past Stonewall and the Glenmary, you will notice a behemoth of a building rising on the horizon. This is the old Sears Crosstown building. One of nine regional distribution warehouses constructed by Sears and Roebuck from 1910-1928, the building has nearly 1½ million square feet, making it one of the largest buildings in the city.

Memphis’ Sears building was vacated by the company almost 20 years ago and has sat empty ever since. It was purchased a few years ago by a local entrepreneur; unfortunately, given the current state of the economy, it is unlikely that it will be redeveloped anytime in the near future. Other cities’ Sears buildings have experienced a variety of fates: Philadelphia’s and Kansas City’s have been demolished. The one in Dallas is now condos. The City of Atlanta purchased the one in that city for various municipal functions (it came to be known as “City Hall East”); it, too, is currently being converted to condos. The buildings in Minneapolis and Boston have been renovated into celebrated mixed-use centers. The one in Los Angeles is still used for various commercial uses and the one in Seattle is now the world headquarters of Starbucks Coffee. Interestingly, Sears’ massive main offices and warehouses in Chicago have largely been demolished, with the exception of the old clock tower, which now stands alone surrounded by recreation fields.

Of course, North Parkway is purely residential and institutional for most of its length, and Sears does not actually abut it. Instead, there is a narrow row of bungalows separating the building from the parkway, but its enormity cannot be missed as you drive past it. Sears is located on Watkins Street, which North Parkway dips under. This underpass also avoids a now defunct railroad line (which presently acts as the terminus of the Vollintine and Evergreen Greenline, a pedestrian and bicycle pathway). The underpass did not always exist. In fact, up until the 50s, the North Parkway-Watkins-L&N RR intersection functioned in a somewhat dysfunctional manner (see below).

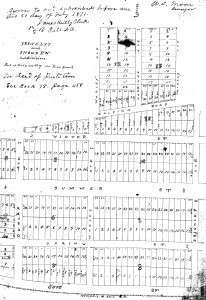

While you are driving through the underpass, take a quick look up at the railroad bridge: an old “L&N” sign still adorns the side. This is somewhat remarkable considering the Louisville and Nashville was absorbed into CSX some 30 years ago. Once you emerge from the underpass, a long row of neat bungalows greets you on both sides of the parkway. This long stretch of bungalows facing a slightly wider parkway median west of Watkins is over a mile long. Indeed, you may note that the North Parkway median stays intact much further into town than did the South Parkway median. The last stretch of median lies between Decatur and Dunlap. Interestingly, the subdivision that lies between these streets was originally laid out in 1871, more than 30 years before the parkway system was established. Nevertheless, the plat from 1871 (see below) clearly shows a very wide Summer Avenue (160 feet wide, to be exact), so this clearly indicates that Summer was at a very early stage contemplated to be a wide, median-ed boulevard.

Given its 1871 pedigree, this stretch of North Parkway can also be considered the oldest stretch of parkway in the entire city. Once you reach Dunlap, not only will you find the median disappearing, but you will get your first glimpse of the Pyramid, that great municipal experiment that seems to create perpetual conjecture on its rightful place among the City’s venues.

The next big intersection is Danny Thomas. This is the end of North Parkway, and as such, your tour of Memphis’ parkways. Although the roadway will run straight through Danny Thomas into the Pinch District and across the Wolf River to Mud Island, the name of the roadway becomes AW Willis Avenue, so it is not technically part of the parkways. At any rate, the roadway has no median and is largely commercial and institutional in nature, so it certainly does not feel like one of Memphis’ parkways. Up until about a year ago, North Parkway did actually cross Danny Thomas: it traversed through what is now the St. Jude campus and terminated at the foot of the Pyramid. The City abandoned its right-of-way in the vicinity of St. Jude and the section west of Third Street is now known as Shadyac Avenue, named for Richard Shadyac, the longtime and recently retired CEO of the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, the fund-raising arm of St. Jude. There was no outcry from the community due to this reduction in the parkway system’s mileage because that stretch of roadway was also very un-parkway like.

This concludes your tour of the Memphis parkway system, now over 100 years old. There are other stretches of roadway that can be considered spurs of the parkway system, including Mississippi Blvd, particularly the section around Booker T. Washington High School, and Riverside Drive, but these were not part of the master plan created by George Kessler more than a century ago. By the way, there is a movement afoot to install medians along some of the median-less stretches of the parkways, so you may find it useful to take this tour sometime again in the near future and enjoy the changes…

Thanks for a great tour! It’s been both fun and educational. I’ve learned a lot from these posts concerning details of existing, but especially descriptions of un-built Memphis.

What’s with “A.W. Willis Avenue” anyway? Why the need for the “A.W.”? This is not the only location our insightful city leaders have renamed city streets in such a manner. Note G.E. Patterson Avenue which replaced Calhoun. It’s as if the family name was not enough, we needed to make sure we had that person specifically. They do realize in a generation we won’t remember who these very specific people were either, right? Willis and Patterson would have sufficed.

Dear Memphis, take a note from Shadyac.

Interesting post Josh. Told me a lot I did not know, and I have lived near North Parkway for many years. Also, good point in the comment about named streets. That was a pet peeve of former councilman John Vergos, to no avail.

John Branston

Interesting post,I enjoyed article and thank for this information.